Moths recently invaded Helen Grimm’s Truro studio. They flutter across a group of small canvases lying on a table and cover her large-scale paintings lining the walls. On some canvases, they are illuminated against midnight blues. In other works, they are camouflaged, sometimes rendered with quick brushstrokes, other times scratched into the surface of impasto paint. They clamor and beat their wings at the same speed with which Grimm paints. Despite all this visual noise, there’s something quiet and delicate in the way they float and rise, weightlessly alighting on her surfaces.

It was on a trip to Italy in April that Grimm began observing bees and became curious about integrating insects into her art. She had been working with inanimate imagery, mostly shells and rocks. “Before I knew it, moths just started pouring out,” she says.

Like her earlier work, the moth paintings deal with repetition and multiplicity. Her paintings, regardless of size, are cropped in a way that suggests an expansion beyond the confines of the canvas.

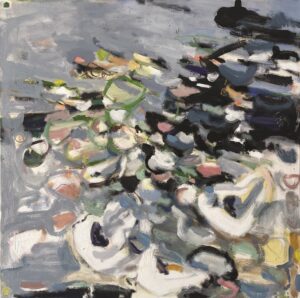

“They are a snapshot of a fleeting moment in time,” says Grimm. The rocks and shells, often depicted at the shore’s edge, are in flux, moved by water and weather. In one such painting, Infinite Possibility, a collection of marks moves in a diagonal composition as if falling at the viewer’s feet. The movement within the composition is matched by Grimm’s touch. Her paint handling is lush and hurried. Some marks coalesce into identifiable oyster shells; other passages are abstracted and unfinished.

Grimm prefers her paintings in this state. “They’re exposed,” she says. “You see the inner workings. There’s vulnerability there.” This painting seems to be in a state of flux, much like the subject it’s depicting.

What distinguishes the moth paintings is a new sense of space. “Suddenly now the subject is in the air,” says Grimm. “It’s lifting up instead of feeling gravity. It’s a completely different experience.”

In the moth paintings, Grimm employs an all-over composition, with the moths set against fields of color. Consequently, there’s nothing grounding the moths; they float through the space. The metaphysical associations in her work have also deepened with these paintings.

“I’m all in with the metaphor around the moths,” says Grimm. “They’re about metamorphosis and transcendence and connecting the earthly and spiritual realms.”

One of the smaller paintings, Flutter, encapsulates this duality between spirituality and earthiness. It’s a light painting. Pale-colored moths fly through a white space, but its ephemerality is tempered with the heaviness of the paint and its agitated application. Here, Grimm capitalizes on what oil painting can do uniquely well: to be both airy and heavy, to merge the spiritual and corporeal. This duality is also present in Grimm’s attraction to shells.

“The inside of a shell is like a jewel, but there they are, stuck in the muck,” she says.

Grimm started painting as a young person. She moved to Orleans at 13 and graduated from Nauset Regional High School. When she went away to college at Cornell her father would send her shells in the mail to paint.

“I was homesick for the Cape,” she says. “It was a connection to who I am.” After college, Grimm lived in California, studied herbalism and then nursing, and eventually returned home. She moved to Truro 20 years ago, and painting regained a central place in her life in 2006 when her father died of a heart attack while fishing off Monomoy.

“Anything can happen at any time, I thought,” says Grimm. “I better get on board with what I really want to do. I remember the first day I started painting again. My twins, Addison and Ella, were about two and a half. It was a turning point for me. I wasn’t ready to let that side of me fall away.”

Since then, Grimm has remained dedicated to painting. For 11 years she balanced her art practice with a job as the nurse at Truro Central School. She left that job two years ago, and since then painting has been her livelihood.

Her life was dramatically interrupted a year and a half ago when Addison, who had a few months earlier told her family about transitioning, died. “It propelled me into grief so hard,” says Grimm.

Grimm’s grief is ongoing, but painting has provided some grounding. “I got back into painting pretty soon after she died because I just didn’t know what to do with myself,” she says. Also, she had a commission she needed to finish. “It was a gift, because it got me in here,” Grimm says. Once in the studio, she found space to process what had happened. “I would be painting, and then I would just be sobbing,” says Grimm. “Painting was a release and a way of processing that wasn’t about thinking.”

When Grimm sits back and looks at the paintings on her studio walls, she doesn’t see grief.

“I feel like I reached through it to that other place,” she says. “It’s definitely through and not around. I didn’t bypass the grief to get to this rosy place. I probably wanted to at times, but it was not an option.” The moths helped her get to that other place, accompanying her through the dark, toward the light, to which they’re drawn, like magnets. “It’s about release,” she says, “and letting go.”

To the Light

The event: Helen Grimm solo exhibition

The time: July 14 to 27; opening reception July 14, 7 to 9 p.m.

The place: Four Eleven Gallery, 411 Commercial St., Provincetown

The cost: Free