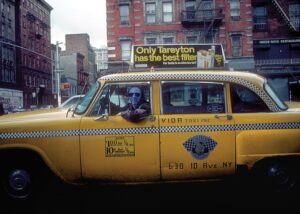

When Stephen Aiken arrived in New York in 1973, the deteriorating, crime-ridden city was practically bankrupt and nearing one of the lowest points in its history, one still remembered for blight, vice, and danger, like a real-life double bill of Taxi Driver and The Warriors on endless replay. But despite the conditions — and in some ways because of them — the city was also a place where creativity flourished, and artists were able to maintain New York’s status as the cultural capital of the world.

Aiken’s black-and-white and color photographs, collected in the new book Artists in Residence: Downtown New York in the 1970s, capture the era in all its evocative, often seedy particulars. Brett Sokol, whose Letter16 Press published the collection, writes in the book’s introduction, “You can practically taste the grit in the air.” A selection from the series is on view at Schoolhouse Gallery (494 Commercial St., Provincetown) through June 23.

The book and exhibition mark the first time the photographs have been shown publicly. The project began several years ago when Aiken started digitizing his photography archive. “Slowly, it came together,” he says. One editor who was interested told him the book would need a foreword. Aiken reached out to Sokol, whom he had met through the Provincetown art scene and who readily agreed to write about his work. “It’s a marriage of words and pictures,” Aiken says.

The pictures themselves are full of vivid detail: a sign for a live chicken market on Chinatown’s Grand Street, a woman’s white coat shining amidst the smudged grays of a street in Little Italy, a worn tenement façade brought to sparkling life in the late afternoon sun. Working in the vernacular of photographers like Helen Levitt and Garry Winogrand who recorded the pulse of New York street life, Aiken photographed lower Manhattan with a sensitivity for light and composition that elevates his images from simple documentary. In their depiction of an edgier if less orderly city than the one that now exists, the photos even embody a certain nostalgia.

Born and raised in Cambridge, Aiken and his then-girlfriend Susan Hannah (the two are now married) moved to downtown Manhattan a few years after he received a B.F.A. in photography from UMass Amherst. “The Vietnam War was ending,” says Aiken. “We were all going somewhere, but no one knew where. New York was a real break for me. It felt like a new beginning.”

Despite his degree, Aiken didn’t consider himself a photographer. “I didn’t feel like I was up to the standard,” he explains in Sokol’s introduction. “I was still in a developmental stage. So it was all eyes and ears, like being a sponge absorbing it all.” Taking pictures became supplementary to his painting and drawing practice, which is his focus today.

Aiken found work helping fellow artists rehabilitate loft buildings that had formerly housed warehouses and factories in Soho and Tribeca. “I didn’t know one end of a hammer from the other,” he says. “But I could talk a good talk, and I ended up learning skills I’ve been able to use my whole life.” The rehabilitation process would eventually gentrify and transform the neighborhoods almost beyond recognition over the decades that followed.

In the mid-1970s, though, the area was still home to a close-knit artistic community. “You can draw a diagram and see how all the artists were connected and how small the art world is,” says Aiken. Between his own art and work projects, Aiken attended the downtown lectures, readings, and concerts that became stages for his photographs — more candid snapshots than formal portraits — of some of the towering cultural figures of the era. Several that appear in the book were taken at a single event at St. Mark’s Church in-the-Bowery in April 1974, including photos of William S. Burroughs, Allen Ginsberg, and a not-yet-famous Patti Smith.

The highlight of Aiken’s artist photographs is a monumental portrait of Joseph Beuys at the New School in January 1974 during his first visit to the United States. Wearing an oversized fur-trimmed coat, Beuys peers wide-eyed at the scene around him, perfectly expressing his self-defined role of artist-as-shaman. By contrast, Aiken’s concert photos of John Cale, Leonard Cohen, and Bob Dylan feel more down to earth and intimate, capturing each artist in the simple act of performing. Aiken says he didn’t need a telephoto lens for his photo of Dylan at Madison Square Garden: “I just made my way to the front of the crowd and bum-rushed the stage,” he says. “There was a lot less security back then.”

While artists feature prominently in Aiken’s project, its title has a more literal origin. The term “artist in residence,” he says, was a category in the city’s zoning code that allowed artists to live in nonresidential buildings; the abbreviation “A.I.R.” was stenciled above doorways on buildings to let fire inspectors know that there were artists living and working in structures that looked abandoned. Aiken himself was one of them, first living in a loft on Lafayette Street near the convergence of Soho, Little Italy, and Chinatown and later in one on the Bowery.

A self-portrait that opens the Schoolhouse exhibition shows Aiken gazing out the window of his Bowery loft onto a street that appears in several photographs in the book. One pair of images taken from the window shows a car parked on the street at different times of day, a study in how changing light transforms even the most ordinary objects. Another shows a woman slumping against a car in one photo and falling to the sidewalk (in what Aiken calls a “junkie nod”) in the next.

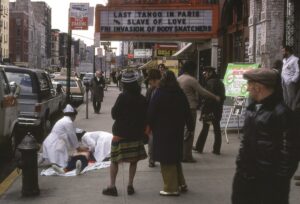

Other photographs feel like single frames cropped from a longer narrative. One of the strongest is a scene from the East Village in which passersby gawk at a prone figure on the sidewalk being attended by two uniformed nurses who seem to have alighted like angels. Movie titles on a theater marquee in the background — Last Tango in Paris, Slave to Love, and Invasion of the Body Snatchers — become commentary on the fate of the fallen subject. When closer inspection reveals that the “person” is actually a mannequin and that the nurses are demonstrating first aid techniques for a clinic advertised on a nearby sign, the scene transforms into something both more comedic and more surreal.

Aiken captures other moments of serendipitous poetry in pictures where signage and typography figure prominently. Tightly framed words on a window of a shop on Lafayette Street — “MOVED OPENED REPAIRED EXCHANGED” — read like a line of haiku describing the transformation of the neighborhood itself.

Interspersed throughout the book are several of Aiken’s own descriptions of the scenes he saw and photographed, which add poetic detail and even sounds to his project:

Perched on a dumpster, a boombox hyperventilates a looping wah-wah and bass line. No one seems to register the overarching caterwaul of a siren heading north towards Beth Israel — that’s someone else’s problem. A little light in his suit, a drunk crows like a vaudeville barker, tips his hat, and bows at the waist.

Aiken currently divides his time between Wellfleet, where his wife has owned Hannah, a shop on Main Street, since 1982, and Mérida, Mexico, where he exhibits his vividly colored paintings and drawings.

While his current experience is half a lifetime and a world away from his formative years in New York, Artists in Residence is, for Aiken, a form of historical and personal connection to a now-vanished place and time.

“Photography lets me exercise my visual memory,” he says. “Did I ever do anything intended for exhibition? The drive has always been more to get something right.”

Photographs by Stephen Aiken

The event: ‘Artists in Residence: Downtown New York in the 1970s’

The time: Through June 26; Fridays-Saturdays 11 a.m.-5 p.m., Sundays-Mondays 11 a.m.-4 p.m., and by appointment

The place: Schoolhouse Gallery, 494 Commercial St., Provincetown

The cost: Free; see galleryschoolhouse.com for information