“I wanted this room to be quiet,” says Gail Bell, sitting in her Wellfleet living room. Outside the windows, traffic and pedestrians flow along Main Street, but she has created a calm space with carefully selected artwork. Above her couch hangs an airy watercolor of boats by Megan Hinton alongside a quasi-abstract painting by Hannah Bureau. Its muted greens suggest a marsh in the rain. Across the room hangs a minimal black-and-white print of simple circular forms by Jim Forsberg, a Provincetown artist who died in 1991. It echoes a nearby ink drawing Bell made herself: an image of black boots painted in silhouette on white paper.

“I love black and white, and I love a good nude,” says Bell. On one wall, Rob DuToit’s ink drawing of a nude woman and tulips, painted on the pages of a book, fits the bill on both counts.

Bell has been collecting art since she was in her 20s living in Dallas. “Anything I could afford that I really liked, I would buy,” she says. “I’m passionate about art, and if I can, I love to support an artist,” she adds.

More than an exchange of commodities, the buying and selling of artwork is an interaction where ideas, emotions, and relationships are nurtured — especially on the Outer Cape, where the business is intimate and local. “We don’t sell art, we give permission to buy what you need to have for spiritual sustenance,” says Berta Walker, owner of her eponymous Provincetown gallery.

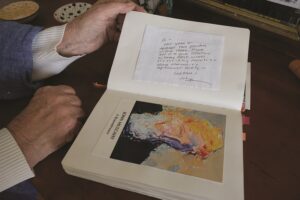

In addition to the spiritual value of the artwork in Bell’s house, the work is also a reflection of her community. She has artwork by neighbors and friends, including a print of Virginia Woolf by Jack Coughlin, who lives down the street. In her kitchen she has a large photograph of a still life with a tea kettle by her daughter, Michelle Edmunds. A scrapbook with postcards of exhibitions sits on a cabinet in her living room, functioning like a record of the life of a creative community. On one page she has pasted a note from John Mulcahy, the late artist and a former neighbor, which accompanied a painting he gave Bell because she had admired it a year earlier. (It’s now hanging in her kitchen.) “I got home one day and there was a plastic bag hanging on the door with a painting in it and this note,” says Bell.

For a collector like Bell, buying artwork is a way of supporting an art community. For many dealers, the motivation is the same — often trumping a desire for profit. “Forming a gallery is a way of creating a sense of community,” says Liz Carney, owner and artistic manager at Four Eleven Gallery in Provincetown. She started her gallery 13 years ago in the Commercial Street home her family owned. “I had the opportunity to rent the space. It seemed too good to pass up,” she says.

Since then, the gallery has shown the work of artists with local connections in a space brimming with colorful paintings. “Profit is not the sole purpose,” says Carney. “We always pay our artists, we always pay our rent, but it hasn’t always been a profitable venture,” she adds, noting that she and all the artists in the gallery have other forms of employment. Yet sales do play a role in sustaining some of her artists. One artist in the gallery recently bought a wood stove with the proceeds of sales.

The gallery serves as a space “where artists see their work being appreciated,” says Carney. And like Berta Walker, she sees the sale as enriching her clients. “Buying art brings a sense of joy and connectedness to another human being,” she says.

Walker’s gallery is among those that have built sustainable businesses by making a decent profit. It has enabled Walker to own a home and a gallery space here. But Walker sees that model now threatened. “I would not be able to open a gallery in Provincetown today,” she says. “I was fortunate to start a gallery in 1990. I could afford a mortgage on a building, find a place to live, and run a gallery for artists.”

To purchase her artwork, Bell frequents a variety of area galleries. One of her favorites is Garvey Rita Art and Antiques in Orleans, an eclectic, visually busy space filled with artwork and antique objects, all assembled by the owner, Kevin Rita, an obsessive collector and art enthusiast. “I’ve gone back a number of times,” says Bell. Kevin Rita’s overflow space in the basement is a favorite hunting ground. “He’s not just one genre,” says Bell. “It’s not just local painting. I like his collection of books and pottery.”

Other galleries on her circuit include Susie Nielsen’s Farm Projects, a short walk from her home. “It’s such a community gathering space, and she’s got such an eye,” says Bell. Unlike many local galleries, which use their walls to maximize the display of their inventory, Farm Projects presents individual exhibitions in an uncluttered white-cube space. GAA Gallery in Provincetown follows a similar approach to exhibiting artwork. With branches in New York and Cologne, GAA’s program is plugged into the global art circuit and less locally oriented.

One distinction of the galleries on the Outer Cape is a closeness to artists. Many are run by artists themselves. Anne-Marie Zehnder grew up in Wellfleet and returned to the area five years ago after living in Boston. In 2020 she bought a small building on Bank Street in Wellfleet initially to use as a studio, but by 2021 she had a full summer program exhibiting other artists’ work.

“Having it operate as a gallery was part of a business model to stay afloat by selling a lot of other people’s work,” Zehnder says. “It would take so much of my ceramic work to keep me afloat.”

Zehnder also uses the space for figure drawing classes. Education and community have become central components of her mission. “I want the space to be almost like a miniature version of a place like PAAM, where serious work is shown and there’s a community of artists and students that have a connection to the space and the art,” says Zehnder. She says her business is “slightly profitable. It’s better than expected in terms of finding an audience and getting people into the gallery and having it succeed,” she says.

Kyle Ringquist is a Provincetown artist who has marketed and sold his own artwork for the past 22 years in a gallery space off Commercial Street. “There’s no middle person, but it’s a lot of work,” he says of his venture.

Keith McLelland, a Wellfleet artist, recently spent two weeks at Gallery 444 in Provincetown, which rents out its neutral gallery space to artists to put on their shows for one or two weeks. “It’s a beautiful shell to work with,” says McLelland. He paid the shoulder-season rate of $1,000 a week for use of the space and made out with a decent profit. “It’s a totally unique model,” says McLelland. “I love it because it gives me the opportunity to have a gallery and do all the things involved with that without having the annual overhead or the stress of making rent month after month.”

Regardless of how much galleries or artists make, their presence adds value to the whole economy and culture of the Outer Cape. One of the major draws of Provincetown and the surrounding area is its creative identity.

“The amount of money it brings to the town, restaurants, and other retail is greater than what is going into the pockets of galleries and artists,” says Carney. “If we didn’t have galleries, it would be a different town.”