Black Artists, Black Lives

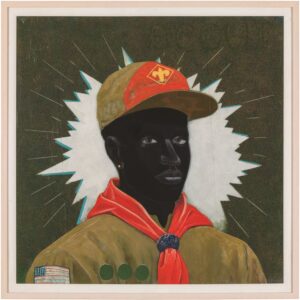

Contemporary African American artists Amy Sherald, Kerry James Marshall, and Kehinde Wiley will be featured in a Zoom presentation by lecturer Bob Potter titled “Reclaiming Black Lives Through Art” on Tuesday, April 25, 10 a.m.

All three artists are noted for focusing on different aspects of the Black experience in the U.S. Sherald, who is best known for her 2017 official portrait of Michelle Obama, combines formal precision and elements of magical realism in her precisely rendered portraits of Black subjects. Marshall, who is regarded as one of the foremost Black artists of his generation, has incorporated his experience as witness to some of the most violent episodes of racial history in America — including the 1963 Birmingham church bombing and the 1965 Watts riots — in his stylized historical tableaux. Wiley’s heroically scaled and instantly recognizable portraits of Black subjects combine historical motifs and design elements with contemporary references to popular culture and current events.

The lecture, which Potter describes as a corrective to the historical absence of people of color in most museum collections, will survey major works by the three artists while telling their own stories and the stories of the people and subjects they paint. It will also include video commentary by the artists.

The lecture is presented by the Creative Arts Center in Chatham. Tickets are $15 ($10 for members). See capecodcreativearts.org for more information.

Walking the Cape With Don Wilding

Don Wilding worked as a journalist on Cape Cod for 36 years and has published three books about the history and culture of the region. A few years ago, he began to translate his written work to a series of guided history walks for the Harwich Conservation Trust and the Eastham Conservation Foundation.

On Saturday, April 22, Wilding will lead a walk in Eastham from Nauset Light Beach to Coast Guard Beach, the setting of Henry Beston’s 1928 memoir The Outermost House. (While the April walk is already sold out, it will be repeated later this year in June, August, and September.)

Beston came to Cape Cod from Quincy in the early 1920s after serving in World War I as an ambulance driver. “He really was taken by this place,” says Wilding. “He ended up leasing some land on what is now Coast Guard Beach in Eastham and soon after built a house there.” In 1927, Beston moved back to Quincy with notes from his time spent living on the beach. When he proposed marriage to writer Elizabeth Coatsworth, she told him that he should use the notes to write a book about his time on the Cape. “She told him, ‘If there’s no book, there’s no marriage,’ ” says Wilding. Coatsworth’s urging proved successful: the book was published in October 1928, and the two were married the next year.

Wilding describes Beston’s style as “like Thoreau, but not as bristly.” The book was influential in the movement to create the Cape Cod National Seashore in 1961.

Wilding will also lead a walk on May 20 on “Cape Cod Rescues, Shipwrecks, and Storms,” focusing on the Portland Gale of 1898. (It will also be repeated in July and October.) All walks cost $20, and registration is required at harwichconservationtrust.org. —Eve Samaha

Elisabeth Pearl’s Singular Visions

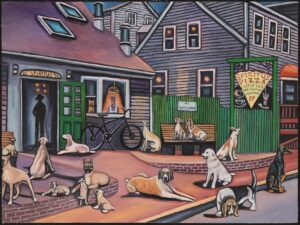

If you didn’t know any better (and somehow missed the information at the entrance), you might think that a new exhibition at the Provincetown Art Association and Museum was a group show of several different artists. Colorful street scenes of Provincetown inspired by American realist paintings of the early 20th century are hung near more delicately painted altarlike assemblages incorporating fragments of electronic hardware, while other paintings in the show approach the sculptural in their thick layers of pigment and roughly scratched surfaces.

Disparate as they look, all the works are by the same person. Curated by artists Mike Wright and Jane Paradise, “Ubiquitous and Familiar: The Paintings of Elisabeth Pearl” showcases the work of a strikingly original Provincetown artist who has lived and worked in the town she depicts in her art since moving here in 1993.

Dogs figure prominently in both a self-portrait on an easel that forms the centerpiece of the exhibition as well as in nearly all of Pearl’s views of Provincetown — particularly in her painting of Spiritus Pizza, where more than a dozen canines lounge, sniff, and generally ignore the “No Loitering” sign on the fence outside the shop. It’s a utopian vision (for pet lovers, anyway) of a town that’s happily gone to the dogs.

The works in Pearl’s “Contemporary Icons” series convey a more techno-spiritual if equally playful vibe: in these mixed-media pieces, Pearl affixes scraps of old circuit boards to panels painted with figures inspired by medieval and Renaissance art, connecting two opposing conceptions of what is “sacred.” Her hand as an artist is most explicit in the abstract works in her “Cosmic” series, the surfaces of which are carved and dug into to create an explicit record of her physical presence and activity.

The exhibition is on view until June 4. See paam.org for information. —John D’Addario

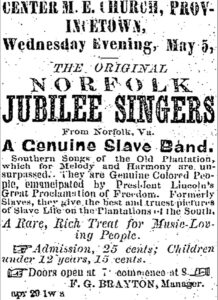

Confronting the History of the Slave Trade

The history of Cape Cod’s involvement with the transatlantic slave trade — and the repercussions of that involvement that are still being felt today — is the focus of the Atlantic Black Box project, a program dedicated to “researching and reckoning with New England’s role in the global economy of enslavement,” according to its website. Atlantic Black Box founder Meadow Dibble will lead a conversation about the project and the history of slavery on Cape Cod at Wellfleet Preservation Hall on Thursday, April 20, 5:30 p.m.

A Cape Cod native, Dibble lived for six years on Senegal’s Cape Verde peninsula, where she published a cultural magazine and coordinated foreign study programs. She founded the nonprofit Atlantic Black Box project in 2018 as a grassroots organization intended to empower communities in New England to reckon with their involvement and complicity in the global slave trade.

Dibble’s own research began in a cemetery in Brewster, where she discovered on a tombstone that a local mariner had died in Africa in 1795. As the founder and executive director of the public history project, Dibble has encouraged Cape Cod residents to search their attics for journals or letters that might help complete stories or begin conversations about involvement with slavery in the region.

Admission to the discussion is by donation, and registration is requested at wellfleetpreservationhall.org. —Dorothea Samaha