“The Provincetown Printmakers,” currently on view at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, makes a case for the significance of a group of mostly women artists who forged new directions in printmaking in the early 20th century. It’s a testament to the power of small things: an intimate community with an outsize significance; small-scale prints dense with color and shape; and a compact presentation of artwork, where a limited scope allows for focused contemplation.

In recent years, museums have been reframing modernism to expand its narrative beyond the historical focus on white, male, and American or European artists. Last spring, the MFA Boston reinstalled parts of its permanent collection to “present modern art from North and South America beyond the standard boundaries of geography, time, and artistic movements,” according to a museum statement. The Provincetown printmakers special exhibition continues to add to this conversation about modernism by highlighting under-recognized women artists — and a marginalized art form that is often overshadowed by painting and sculpture.

The printmakers in the show are known for their white-line prints, a technique introduced to Provincetown by Swedish-born artist B.J.O. Nordfeldt in the 1910s and developed among artists in a spirit of generosity and collective innovation. Traditionally, multicolor woodblock prints — like the ones on display in a concurrent show of work by the influential Japanese artist Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849) — were created by using different blocks of wood to print each color. White-line prints are created with only one block: sections are colored separately and printed in succession. The result leaves white lines demarcating different areas of color.

The exhibition focuses on the work of six artists: Ada Gilmore Chaffee, Mildred McMillen, Maud Hunt Squire, Ethel Mars, Juliette Nichols, and Nordfeldt. Taken as a whole, the works establish the importance of Provincetown as an art colony in the first half of the 20th century and emphasize the group’s dominant visual concerns and motifs: layered, compressed space; the interlocking of figure and ground into dynamic puzzle-like compositions; and a use of flat, chromatic color.

The exhibition also includes works by other artists who were instructed and inspired by the original group of Provincetown printmakers. Blanche Lazzell (1878-1956) has long been regarded as the dominant figure of that later generation, and in many ways she is the star of the show. A case at the center of the exhibition contains examples of her wood blocks, which are equal to her prints in their value as art objects. Unlike the delicate white lines in Lazzell’s prints, there’s a physicality to the lines in the blocks that were used to produce them.

One block depicts Lazzell’s studio in winter. The small structure sits against the water amidst drifts of snow, rendered with sharp lines that cut through the wood and stains of color through which the wood grain bleeds. In another block, Lazzell uses deep autumnal colors in a turbulent composition of beached boats.

Lazzell’s prints are the most abstract of the group, her interest in Cubism most apparent in her exploration of Provincetown’s blocky homes and industrial wharfs. In The Pile Driver, her most abstract picture, a red triangle foregrounds a group of homes, represented as a jumble of colorful shapes. A pair of trees and a church on the horizon provide depth in an otherwise compressed, shallow space. Trees and a church, along with the omnipresent deep blue harbor peeking through the narrow streets, contrast the sharp-edged structures of a working town. In Lazzell’s work, the viewer sees Provincetown as a Cubist paradise and an ideal setting to explore tensions of the emerging modern world — tensions that mine the fractures between artifice and nature, industry and domesticity, and abstraction and realism.

The modernist project is reflected to varying degrees in works by other artists in the exhibition. There’s a consistent emphasis on flatness and geometry, an inherent quality of the medium. In Ethel Mars’s print of a woman playing the piano, the figure is sandwiched between the flat patterns of her dress and the wallpaper, the piano represented as a dark silhouette. It’s a masterful use of shape and pattern to suggest spatial relationships. This print is typical of others by Mars, which focus less on Provincetown as a subject and more on female figures playing the piano, dining at cafés, and lounging in interiors.

Originally from Springfield, Ill., Mars moved to Provincetown from Paris, joining other American expatriate artists fleeing World War I and settling in what was at the time the country’s foremost art colony. (Juliette Nichols, represented in the show by a pair of playful prints of horses and figures rendered in swirling forms, followed the same trajectory.)

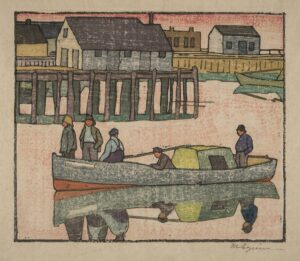

Mars lived in Paris and Provincetown with Maud Hunt Squire, an accomplished book illustrator. Groups of figures — usually fishermen — dominate Squire’s nautical scenes. Body language and interactions between her figures convey personalities and the dynamics of human interaction among working men. In Evening, a group appears to return from a trip, reflective and tired in the pink glow of sunset. In another picture, fishermen sit on a dock, some speaking to each other, one seemingly dejected or exhausted, another eavesdropping from a door. Squire’s background in illustration likely nurtured the emphasis on character and narrative evident in her prints.

The question of what separates “fine art” from mere “illustration” is a thorny topic, and the works in this show stand on both ends of this continuum. Like Squire’s prints, Ada Gilmore Chaffee’s works read like illustrations in that they’re primarily concerned with depicting a scene rather than forging new artistic territory or articulating a formal vision (as Lazzell does so compellingly). Perhaps part of the point of the show is to blur some of those distinctions. However they’re categorized, Chaffee’s charming prints — like The Silva Sisters, an image of two women walking and holding flowers, and Provincetown Christmas, a lively street scene rendered in saturated color — convey a joie de vivre in their scenes of town life.

Many of the artists in this show were significant both as practitioners of white-line prints and teachers of the technique. While Ada Gilmore Chaffee’s husband, Oliver Chaffee, is acknowledged as having taught the technique to Lazzell, the original innovation is credited to Nordfeldt. His three prints in the show stand out from the others in their restraint and muted palette, likely an influence of his time studying traditional Japanese printmaking. Nordfeldt’s pared-down compositions typically feature a dominant object or group of objects in the foreground: a tree, a group of rocks, drifting sailboats. His prints, all from the first decade of the 20th century, are the oldest in the show. By 1915, he had shared his innovation with others in Provincetown; it continued to evolve and proliferate through the collective efforts of the other artists in the show.

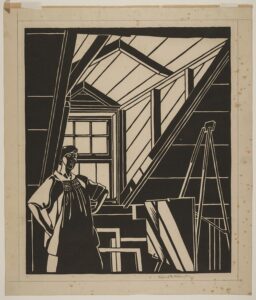

One of the fun things about the show is exploring the many connections between its artists. Mildred McMillen was close with Ada Gilmore Chaffee, whom she met at the Art Institute of Chicago, and Ethel Mars taught McMillen the white-line technique, which she used to striking effect in black-and-white linocuts. With its sharp composition, raking light, and complex line work, McMillen’s The Attic Window is one of the strongest works in the show, one that can be read as both a geometric abstraction and as a straightforward portrait. The subject stands with her hands on her hips in the corner of the picture, owning the space around her. The scene embodies the confident and powerful spirit of a community of artists and friends who innovated together to create works of art still resonating a century later.

Making Their Marks

The event: “The Provincetown Printmakers”

The time: Through Oct. 15, 2023

The place: The Museum of Fine Arts, 465 Huntington Ave., Boston

The cost: $27 general admission; see mfa.org for more information