Although Truro-based artist, curator, and teacher Megan Hinton never met Florence Brillinger or Janice Biala, their work has strongly informed her own art practice.

We met recently at the Provincetown Art Association and Museum to discuss these two 20th-century artists with strong ties to Provincetown. Brillinger was born in 1891 in Emigsville, Pa. and showed her work here in the 1920s and 1930s. She frequently traveled and worked in Europe and exhibited her abstract paintings in the 1940s at the Museum of Non-Objective Painting in New York, a predecessor of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. She spent her last years in Andover, where she died in 1984.

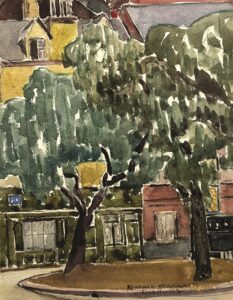

“This painting, Rouen, hangs in my office,” said Hinton. “It provides me with a connection to a painter — a woman — who worked in Provincetown. When I look at it, I wonder about the trajectory of her life and why there’s not a lot of information about her. Is it because she was a woman? Because her work was underrated? I don’t really know. But I feel a sisterhood of sensibility, a kinship. I feel connected to her process and the way this painting looks.

“For me, there are two things that make a good painting. One is color relationships, and the other is the way the paint is applied. Brillinger’s applications are so rich and confident. The watercolor is not light and dainty — it alternates between light marks and opaque ones. When two forms come up against each other, there’s either an overlap or there’s a holding back that creates a white line. That original surface of untouched paper becomes a necessity of composition. I’m also often thinking about this in my own work.

“She did a number of these small, realistic snapshots that I think are from her travels in France. This one is titled Rouen, dated 1925. She was probably looking at Impressionist works, and maybe came across Hawthorne. It seems like she’s giving herself permission to jump beyond traditional means of painting. In my own work, I think about what’s made up and what’s actually there. We can paint a tree or a street scene the way we see it, but then when you keep working you have to add or negate something in order for it to thrive as a painting. That’s what I’m seeing in her work. There’s poetry in the way that an image is transformed, although it maintains something of its original quality. It’s something that painting can do that nothing else can.”

Janice Biala, born Schenehaia Tworkovsky in 1903, emigrated to New York in 1913 from Biała Podlaska, a small city in eastern Poland. She arrived with her mother and brother — who became the renowned artist Jack Tworkov — to join her father, who had a tailor shop on the Lower East Side, and older half siblings. Biala studied with Charles Hawthorne at the National Academy of Design, and Hawthorne introduced the two siblings to Provincetown, where they both studied and continued to visit throughout the 1920s. Biala also lived in Paris and traveled frequently with her partner, the writer Ford Madox Ford, until his death in 1939. She was active in New York and Paris until her death in 2000.

“I first saw her work at Tibor de Nagy Gallery in New York about four or five years ago,” Hinton told me. “What’s remarkable about Biala is that she decided at the height of non-objective New York School painting to deal with realism. This was not necessarily a trend of the time.

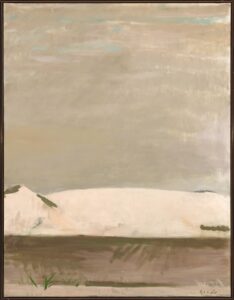

“I like her painting View of the Bay, Provincetown a lot. It’s dreamlike, perhaps influenced by surrealism. She’s using this brown color as a veil to what’s outside. It’s an overlay of another space that makes for unconventional landscape painting. I think she was very much a free spirit, and it seems like there’s something subconscious going on in these works.

“The square lines of the brown window frame are freshly painted and not over-considered. They show how an edge is just about how a brush meets a surface. I think that she was conscious of the fact that if she kept it in this unfinished, informal state, the image would maintain a sort of freshness.

“There’s a playfulness in her process. We see a chair, but the chair also takes on this kind of abstraction. It’s a collage element — painted paper. The chair could be described as crude or childlike, but at the same time it meets the verticality of the windows and the piers in the distance. She was figuring out spatial relationships between what’s in the front, middle, and background.

“There’s also a very limited palette in her work. I’m interested in that in terms of my own process — limiting the palette in order to accentuate the most powerful statement. She was taking color field abstraction into image-based work. It wasn’t until Philip Guston did a series of image-based paintings in the 1970s — which at the time was very controversial — that imagery came into an abstract expressionist style of painting. She was ahead of her time.

“I think that she was giving herself permission to explore without worrying about the viewer. She doesn’t seem like she was self-conscious. To me, that would suggest that she was a strong, independent woman. A lot of us are still thriving in the kind of bohemian lifestyle that Brillinger and Biala experienced. I can feel that experience in the playfulness, passion, and confidence of their painting. I think they were truly doing what they wanted to be doing.”