French filmmaker François Ozon is a bit of a chameleon. He’s best known for the film Swimming Pool, with Charlotte Rampling as a British mystery writer vacationing in Provence. But his body of work — he’s been at it for nearly 30 years — is wildly diverse, from the period drama Frantz to the gay teen Summer of ’85. One of his earliest features, Water Drops on Burning Rocks, is an adaptation of a play by Rainer Werner Fassbinder, whom Ozon deeply admires.

Like Ozon, Fassbinder was prolific — he directed 38 feature films and 3 miniseries over a period of 13 years, dying at age 37 in 1982 from an overdose of cocaine and barbiturates. He was openly gay — as is Ozon — both men’s films have often dealt with homosexual desire and doomed relationships.

The link between them has recently been cemented. Ozon’s latest effort, Peter von Kant, which was released in 2022 and can now be rented on streaming sites, is essentially a remake of Fassbinder’s 1972 classic, The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant. The change from Petra to Peter is a clue to the biggest alteration Ozon has made: the main characters in the new film are both male, while Fassbinder’s Bitter Tears is a lesbian melodrama with an all-women cast. But beyond the gender flip, Ozon has turned his movie into a semi-biographical ode to Fassbinder himself.

Which is not as big a change as it sounds. Bitter Tears, despite its female leads, is in many ways a mirror of Fassbinder’s life and loves. Petra (Margit Carstensen) is a fashion designer living in Bremen, a large port city in northern Germany, who is introduced to a beautiful young woman, Karin Thimm, played by Fassbinder muse Hanna Schygulla. Petra, who has been married twice, disastrously, and has a teenage daughter in boarding school, falls for Karin instantly and obsessively. She invites the young woman to move in and become her model, and they have a brief and tempestuous affair. All the while, Petra’s live-in assistant, Marlene (Irm Hermann), hovers around mutely, taking orders like a slave.

Bitter Tears is based on a 1971 play by Fassbinder, written for his radical theater troupe in Munich, which included Schygulla and Hermann. Little is done in the movie to mask the limited, theatrical nature of the narrative, which takes place entirely inside Petra’s apartment. Despite this, it feels thoroughly cinematic and indelibly Fassbinder — a wonderworld of fluid pans and diverting poses, outré ’70s fashion, and smoldering, neurotic passion.

In the years when the play was written and adapted to film, Fassbinder was briefly married to one of his actors, Ingrid Caven, and began an affair with El Hedi Ben Salem, a beefy Moroccan man who left his wife and five children to be with Fassbinder. Ben Salem was cast as the titular lead in Ali: Fear Eats the Soul, Fassbinder’s 1974 breakout international hit, but before long he was dumped by the director and had a violent mental breakdown, eventually hanging himself in jail. The two men’s early relationship is mirrored by Petra and Karin, and even Irm Hermann’s Marlene resembles the role Hermann actually played in Fassbinder’s life.

These autobiographical echoes have been made literal by Ozon 50 years later in Peter von Kant. Peter is a filmmaker, not a designer like Petra, and the beautiful young man he falls for is one Amir Ben Salem (Khalil Gharbia), who shares El Hedi’s last name. Peter looks like Fassbinder and even dresses like him. And he casts Amir in one of his films.

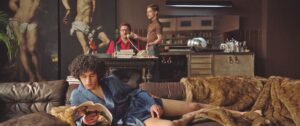

Ozon has trimmed Bitter Tears by about a half hour, but the scenes are remarkably similar in both films, with the dialogue often matching line by line. Some dated references to race and sex have been smoothed over, and the location of Peter’s apartment is moved to a stately building in Köln, viewed from the outside (Bitter Tears has no exterior shots). The actors speak French — which is unexplained and disconcerting — and the shooting style is crisp and seamless, with none of Fassbinder’s self-conscious flourishes. Though the production design is faithful to the period, it’s lovely and slick, unlike Fassbinder’s low-budget, shabby-chic sets, costumes, wigs, and makeup, which are like a drag queen fantasy. (Even so, Ozon kept the white shag carpet that’s so prominent in Petra’s bedroom.)

Meta references to Fassbinder and European art cinema of the ’70s abound in Peter von Kant. Hanna Schygulla, now 79, plays Peter’s mother. As Peter’s cousin Sidonie, an aging screen siren, Ozon cast Isabelle Adjani, who became a major star in 1975 in François Truffaut’s The Story of Adèle H. Aminthe Audiard, the grandniece of French filmmaker Jacques Audiard, plays Peter’s daughter Gabriele. Even the poster for the movie, which shows a naked Peter embracing Amir from behind and licking his ear, is a reference to Andy Warhol’s blue and red silkscreen poster for Fassbinder’s Querelle.

All of this might excite film buffs, but it doesn’t add up to a great work of art. Fassbinder certainly deserves the adulation, and there’s something genuinely refreshing, even honest, about turning Bitter Tears into a gay male sexual obsession. But making the film about Fassbinder instead of in the style of Fassbinder removes the essential elements of his genius. There’s little feel in Ozon’s film for the working-class victimhood that permeates all of Fassbinder’s work. And we’re likely to excuse the flaws of Peter/Fassbinder in a way that undercuts the tragic resonance of his romantic failure.

In other words, it might have served Ozon’s purpose better to do a fictional film about the making of Bitter Tears instead of re-making it line by line in a way that highlights its creator’s connection to the material. Classics are classics for a reason. Sometimes it’s best to leave them alone.