For Ruby T, who moved to Provincetown in 2021 after living in Chicago for more than a decade, making art is a means to explore overlaps between the political and the sensual. It’s a synthesis that wasn’t always easy for her to achieve.

Currently, she works out of a basement-level studio at the Provincetown Commons, its tables spread with artwork grounded in drawing but often crossing into other territory, including painting and fibers. Her artwork pulsates with detailed quivering lines, juicy color, and an indulgent range of materials.

The artist does not use her legal surname professionally, in part, she says, because people often mispronounced it. Abbreviating her last name also gave her a sense of freedom. “I feel like ancestry carries a lot of heavy weight,” she says.

Ruby T’s interest in art and politics began when she was a child growing up with activist parents in Somerville, where she learned early on that having a political consciousness could be both a burden and a blessing. “I had a heavy dose of going to protests and meetings at a very young age,” she says. “I grew up in a city and public school system with lots of inequity and authoritarian values, and in a family with lots of political consciousness. I came of age feeling that artmaking with a social function as well as grassroots organizing efforts were more worthy of my energy than artmaking that didn’t necessarily have an overt political goal.”

Along with strong commitments to various social and political causes, art was a central tenet for Ruby T’s family: her mother, Cynthia Bargar, is a poet, and her father, Nick Thorkelson, is a political cartoonist. (Both moved to Provincetown in 2019.) As an undergraduate at New York University, she tried to bridge the gap between politics and art by creating her own major. After receiving her degree in arts-based community development and activism, she left for Chicago in 2008, for what she thought would be a temporary flight from New York’s financial crisis. But she ended up staying longer than she expected.

“I got really invested in the city, and kind of fell in love with the DIY, queer, arts, and noise music communities there,” she says. Soon, she began working at a feminist art gallery. “It provided some really incredible opportunities for me to put ideas that I had from my undergrad education into action,” she says. “I was spending a lot of time in meetings, at protests, and organizing actions and cultural events, both in and outside of my job. I was running around constantly.”

During her time in Chicago, she eventually began disentangling her art from direct political action. “I was realizing that political and artistic production don’t necessarily always have to intersect and wrap around one another in order to be viable or valuable in my life,” she says. She pursued an M.F.A. at the Art Institute of Chicago and had a solo exhibition at the Chicago gallery Western Exhibitions in 2019, where she showed a series of sensual and playful drawings that began as marbled paper and were embellished with cartoonish images and lines.

“I spent a lot of time reading comics, drawing comics, and also watching my father draw comics,” she says. “I think that a graphic style is imprinted on me.” As part of her solo exhibition, she produced a chapbook called Draw Him to Death, which featured 110 cartoons of South Carolina Sen. Lindsey Graham deftly drawn with an acidic and comedic flair.

A bedbug infestation in her apartment building and the aggravations of living in a city during Covid finally pushed her out of Chicago and into the arms of Provincetown, a place she’s been connected to since childhood visits with her family and working summer jobs in college. (Currently, she works at PAAM as curator of museum education.) In her Provincetown studio, she continues to build on her prior work while also bringing more local experiences into her practice.

Water is a consistent motif in Ruby T’s work. Drops of water and flowing eddies punctuate many of her drawings. One table in her studio displays a group of ink drawings done on location on Lake Michigan and by a stream in Wassaic, N.Y. during a residency. A group of recent charcoal and pastel drawings depicts a more local source: the Atlantic Ocean, in all its tumultuous glory.

But even in or near the water, Ruby T can’t escape politics. “As somebody who spends a lot of time thinking about how oppressive structures circumscribe and limit our expression, I feel like water has a lot to teach me about change, flow, and soft power,” she says.

An emphasis on experiences that are open-ended, provisional, and fluid is conveyed by the fragile nature of her works on paper and use of materials like silk and canvas. “I’m using the making of the work as a laboratory to practice and build sensual forms of knowledge as opposed to more verbal and fact-based ones,” she says. In doing so, she feels connected to decorative and domestic visual traditions, where “emotional and femme knowledge has always really thrived.”

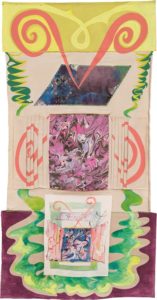

This approach is evident in Tapestry for Temple of Spiraling, currently on view at Western Exhibitions in Chicago, in which divergent visual languages are brought together. There are nods to domestic traditions in the stitched and embroidered edges, while a passage of marbleized canvas commands the center.

An in-process painting of a meadow in her studio reverberates with similar contradictions and complexities. “I’ve been experimenting a lot with silk and drop cloth and how they behave materially when they touch each other,” she says. In this painting, the two materials are stitched together to create a base for a fluid and open-ended painting that feels alive with the intense color of a field in summer. Its frenzied marks meander across some sections of the canvas while other portions remain open and empty, imbued with potential. “It feels like a very queer project of exploring and experimenting with multiplicity and fluidity as a way of generating sensual knowledge,” she says.

This interest in queer aesthetics and queer femininity feels very much of the moment. But along with a particular style, Ruby T is also invested in struggle, which is what politics is all about. The resolution between style and struggle is perhaps best illustrated in Ruby T’s marbled surfaces, an art form — often denigrated as “craft” — that she reclaims.

“When I paint or draw on marble, I’m enacting a power struggle between my line’s attempt to represent or approximate moving water and the physical print of actual moving water, frozen in the marble pattern,” she says. “It’s really healing and restorative for me.” To the casual viewer it may just look like a pleasant and colorful image. But underneath — and in its making — Ruby T finds resolution between her agency and the stubbornness of a material structure. It’s not unlike locating oneself in a political world.