In her film Untitled (burned rubber on asphalt), 2018, Tinja Ruusuvuori turned her attention to a small community in Norway where she probed one town’s minidrama about a mysterious person who marks up the roads with skidding tires. The action, or lack thereof, takes place over 20 minutes amid soaring mountains and pristine, misty landscapes captured in slow, panoramic shots. The stillness and purity of the environment, along with the sleepy town — where it’s apparent that not much happens otherwise — place the skid marks in stark relief, like charcoal sketches on a blank page.

The mood of Ruusuvuori’s piece carries throughout the current exhibition at the Provincetown Art Association and Museum, which features work by eight of the 10 current visual arts fellows at the Fine Arts Work Center. The work is sparsely hung and often small. There’s a sense of calm and quietude throughout the exhibition, in contrast to last year’s busier, more colorful show. The subdued energy allows for a heightened viewing experience and a clear space to highlight the individual marks of each artist. Some of these marks are as brash as those of the speeding driver in Ruusuvuori’s documentary. Others are more controlled and restrained.

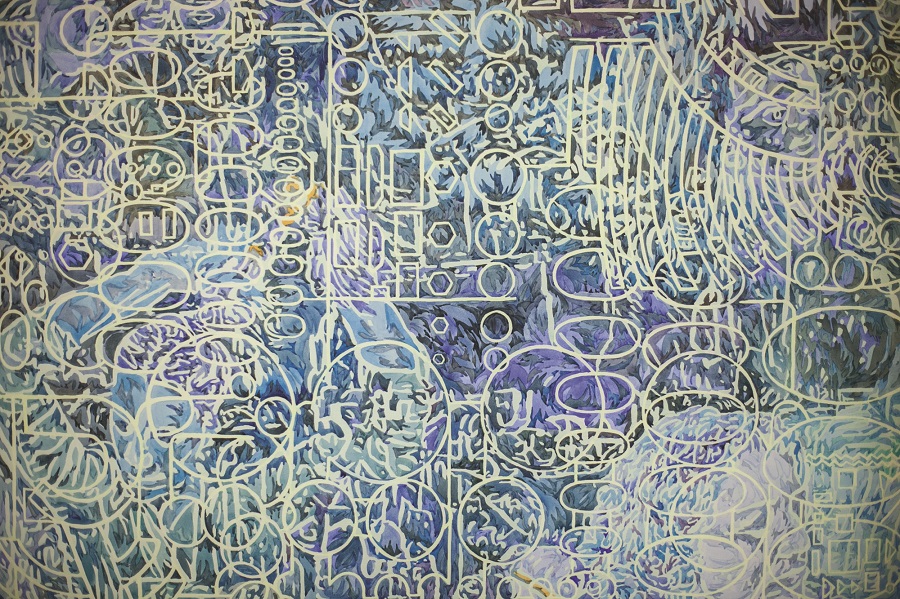

The exhibition is anchored at both ends of the gallery by large multi-panel paintings. At one end, Siennie Lee explores tension between organic and geometric forms in her triptych, Foliage of the Seas. In this delicate painting on silk, Lee creates an all-over composition with lush organic forms, rendered in subtle variations of blues and greens and overlaid with rigid, geometric shapes that appear like an electrical diagram. The combination creates a soft, pulsating energy that’s equal parts synthetic and natural.

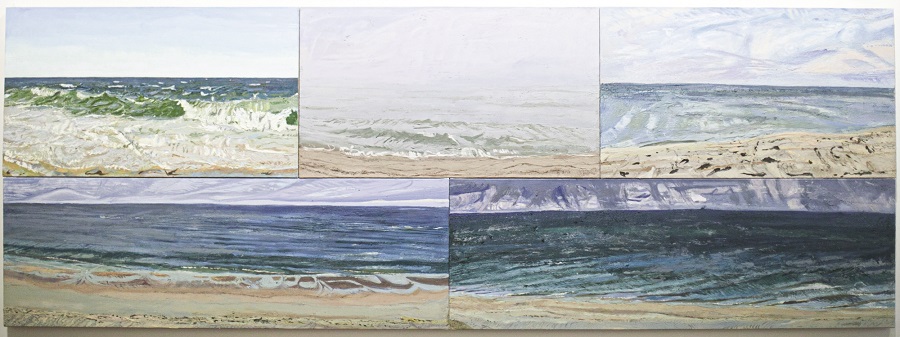

At the other end of the exhibition space, Elizabeth Flood takes an entirely different approach to materials in her commanding five-panel painting of Race Point. She mixes sand into her paint and applies it thickly in energetic gestures. But despite the material heft, a sense of quiet permeates the work: not just in the imagery of calm seas and clear skies, but also in a limited palette and an emphasis on horizontal lines, which ground the viewer. The only image without a horizon line in the five-panel composite is a gray seascape where sea and sky merge, and its amorphous quality creates an ethereal, mysterious void at the center of the work.

Sichong Xie also incorporates water imagery to create a poetic meditation on mortality. In her video piece, filmed at a lake in Skowhegan, Maine, a woman swims and sits on a chair on a dock while reading a text. Her words — both philosophical and personal — narrate the video, which progresses into wide-angle views of a couple rowing a boat on a placid lake. “How can you create an experience of being alone?” the narrator asks. The characters, small and rowing toward some intermediate place, conjure existential anxieties, which are eased by the beauty of the environment.

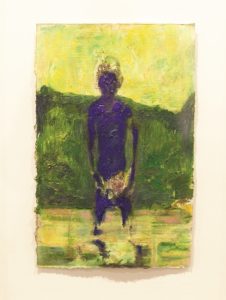

Nearby, Blake Daniels and Mark Joshua Epstein pack intense visual experiences into their small paintings. Daniels’s Morning Wader in Vaal River depicts a figure silhouetted and standing in a river as lushly painted mountains rise in the distance. The yellow-green palette and hazy edges create a hallucinogenic atmosphere from which the figure emerges like a ghost materialized in globs of blue paint.

Epstein’s similar-size painting on paper is equally dense with color. In this fastidious abstraction, he works with flat shapes of color and curves that wrap around the composition and bubble outward from one edge. The painting shows an interest in pattern and decoration, but the controlled tenor of the work finds release in a large central area, where green streaks, loose and liberated, run across a purple ground.

Also working with shape-based abstraction, Kristy Hughes’s body-sized works, which merge painting and sculpture, are the loudest pieces in the show. Before coming to FAWC, Hughes was the coordinator of the Elizabeth Murray Artist Residency on the former grounds of Murray’s farmhouse in upstate New York, which celebrates the late artist’s commitment to creative risk-taking. Like Murray, Hughes is interested in expanding painting beyond two dimensions. One of her pieces hangs on a wall, its shapes layered in relief. It seems to grow a leg that connects it to the floor. Another, Shape of a Rock (Heart), plays with the presentation of a sculpture on a pedestal — but here, the pedestal is part of the sculpture. Hughes seems to enjoy the process of contesting how art objects are approached by the viewer.

Georgia Dickie’s installation Promiscuous Availability appears from a distance like a pile of junk that someone left on the floor, perhaps anticipating a viewer’s reaction. (After all, what contemporary art show doesn’t have at least one installation that looks like a pile of junk on the floor?) But a closer look reveals that the piece is actually a carefully constructed arrangement of quotidian objects like cardboard boxes and empty food containers. In her statement accompanying this piece, Dickie discusses her interest in reassembling found objects “into new arrangements based on a logic of eschewing and rebalancing their assigned functions.”

The fellows, who are about halfway into their seven-month residency, will begin their individual exhibitions at FAWC’s Hudson D. Walker Gallery in February. Like the Norwegian community in Ruusuvuori’s film, the Outer Cape this time of year is a place where stillness and natural beauty provide space to create, ruminate, and cultivate minor dramas. It will be fascinating to see how this experience informs the mark this group makes.

Meet the Fellows

The event: A group show by the 2022-2023 Fine Arts Work Center visual arts fellows

The time: Through March 5

The place: Provincetown Art Association and Museum, 460 Commercial St.

The cost: $15 general admission