In our thing-filled culture, our super-documented lives, what happens in the liminal spaces? What happens in those nothing-moments as we leave one place (either physically or mentally) and move toward another? In the between?

Susie Nielsen, who runs the innovative and inspiring Farm Projects gallery in Wellfleet, is obsessed with such moments. She describes them as those “awkward, unlabeled times that are important but that we’re always trying to avoid.”

I asked Susie if she’d want to “Mad Libs” a poem because, in my experience, she’s the kind of person who is eager to jump into new stuff, take chances on creative ideas, and play. At Farm Projects, she is always expanding the concept of what a gallery can be.

Susie says that, while she isn’t a poet, she loves music. “Music was always about getting the liner notes,” she says. “They always decided whether I got an album or not.” She loves songwriters who play with language by doing things like using double negatives or switching up the order of their sentences. One of her favorite lyricists is Dave Berman, who was in Pavement, Silver Jews, and Purple Mountains, and wrote a book of poems, Actual Air. Susie also admires songwriters Steve Malkmus, Bon Iver, and Bob Dylan. “You can read his lyrics like a book,” she says of Dylan. “I don’t even listen to his music anymore, but I can still read his lyrics.”

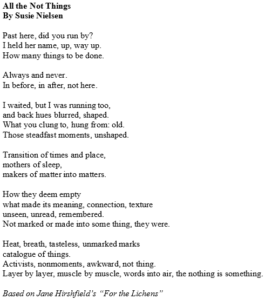

As with other “Mad Libsers,” I sent Susie a few poems and asked her to pick one and use it as a template for her own writing. She chose “For the Lichens” by Jane Hirshfield, a poem about discovering a long-overlooked wonder. When I asked her why, Susie said, “I didn’t recognize Hirshfield’s name, so I looked her up, and I just kind of fell for her. I loved that she was but wasn’t an academic, that she was rooted in Buddhism, that she doesn’t say too much.” I understand Susie’s reaction. Hirshfield has a quietness, a centeredness, and an aura of deep care that is utterly compelling.

Susie printed out the poem and started identifying every part of speech but says that she then “started getting tangled up in grammar and overthinking it.” She tends to work intuitively in her art practice, and she needed to bring the same spirit to this poem. “Overthinking things clogs me up,” she says. “I tend to be more responsive or reactive.”

Once she stepped back and let the reins loosen, the poem came together. “I’d gotten this idea about a collection of nothings, and I just started to write,” she says. I appreciate in Susie’s poem how she emphasizes the forgotten, the “unshaped.” She reminds me that “the nothing is something,” which is a comfort on days when I feel like I’m spinning my wheels.

Susie ended up keeping a couple of lines from the original poem: “What you clung to, hung from: old” and “unseen, unread, unremembered” (though she changed the last word to “remembered”). She was a little worried that she was breaking the rules, but I’m so glad she did! It’s lovely to hear Hirshfield’s lines understood in a new way and used in a new conversation. I love how they ghost up in this new poem, whispering about its origins.

After finishing the poem, Susie let it sit for a day. Then she went back to both Hirshfield’s poem and her own.

“For some reason I was able to read it differently,” she says. “I was able to connect to it. When I looked at the poem again and read ‘those nameless ones,’ I understood it differently. I think a lot about collecting and our urge to collect, and her poem talks about that, too: there are these tiny textures in your life or on a tree — you don’t know they’re doing anything, then one day it’s made something. It’s a collection. I read it to my husband, and he said, ‘Wow that sounds like a poem.’ ” I agree.