TRURO — Andre Davis, 23, graduated this month from Morgan State, a historically Black university in Baltimore. His first steps out of college have brought him to Truro, where he and recent graduate Kendra Tyler are fellows in a residency program created by a partnership between the Truro Center for the Arts at Castle Hill and the university.

The residency, which happened for the first time last December, enables two recent graduates to live and work at Castle Hill for two weeks. Fellows are provided with housing, studio space, a $500 stipend, transportation, and mentorship. The program’s creators hope to accommodate participants in both the fall and spring.

“It’s a good stepping stone to professional life,” says E.L. Briscoe, a lecturer in visual arts at Morgan State. On a windy morning with the season’s first snow dusting the grounds of Castle Hill’s Edgewood Farm, he sat at a large wooden table with Davis and Tyler, who had arrived two days earlier, discussing the residency and their plans for the upcoming two weeks.

“I’m working on an installation,” says Tyler, 24, who graduated last May and teaches art at an elementary school in Baltimore. She’s currently working with Styrofoam and clay and planned to forage for moss, leaves, and sticks in the woods around the property. “It’s a continuation of previous work,” says Tyler. “I like to bring in natural elements to an inside space.”

Davis, her studio mate for the residency, typically works in illustration and painting. “Drawing is the first thing I remember really enjoying,” says Davis. “I figured, why not go to school for this and build upon it?

“Usually, I draw from past experiences,” he continues. “It could just be everyday things like walking to the corner store, meeting up with friends, cookouts, funerals — a whole spectrum of the human experience but through the lens of somebody that grew up Black in Baltimore. Back home, my process is a ritual. I can’t really do that here. There’s no corner store in the middle of the woods. It’s real quiet here. You have more time to think about what you’re doing and why you’re doing it. It forces you to dig deep.”

The opportunity for Davis and Tyler to come to Castle Hill was the result of a $100,000 donation from Nancy and Al Osborne. “I wanted to do a major gift to celebrate the 50th anniversary of Castle Hill,” says Nancy Osborne. “At the same time, the Black Lives Matter movement was happening in response to the murder of George Floyd.” She participated in a brainstorming session to identify ways that Castle Hill could make changes to address issues of diversity, equity, and inclusion. “What struck me,” says Osborne, “was one common point: if we wanted to attract a more diverse audience and students of color, we had to finance scholarships and residencies.”

Castle Hill workshops typically cost around $500 for a one-week course, not including housing. The residency program at Edgewood Farm, which hosts three or four artists in the fall and spring, costs $850 for two weeks or $1500 for one month, including housing and studio space. Another program called the Yellow Chair Salon, led and developed by Michael David, costs $725 for an eight-session online program and $3,500 for a two-week in-person master class, including housing and studio space.

“It’s hard to get out here. It’s expensive,” says Castle Hill Executive Artistic Director Cherie Mittenthal. “We try to take out barriers to allow more people opportunities.” So far, initiatives have included the awarding of full or partial scholarships to 28 participants last summer — just 2 percent of the 1,400 students who enrolled. Other initiatives to expand access include 20 scholarships for local students, an after-school program at Truro Central School, and fully funded off-season classes for local residents over 65, which serves between 40 to 80 people each year.

Despite these initiatives, Osborne and others saw a continued need for Castle Hill to grow. Would the next 50 years bring about a more inclusive institution — or one that would grow ossified, a sort of gated community for those who could afford it?

Osborne, who lives part-time in Truro, became involved with Castle Hill during a professional rebirth. “I became interested in pursuing art after a business career, which included working as an executive at Walt Disney for 16 years,” she says. She now creates abstract bronze sculptures exploring gestural movement. “I started taking classes at Castle Hill in 2009,” says Osborne, “and I immediately fell in love with the place.”

After the brainstorming session in 2020, Osborne considered what she could do. “I was sitting on my couch and thought, ‘It’s time for me to step up to the plate,’ ” she says. “So, I proposed an idea to my husband: a Castle Hill artist residency in collaboration with historically Black colleges and universities, for which we would donate the initial seed money.” Her husband, Al, an economist and senior associate dean at U.C.L.A.’s Anderson School of Management, agreed.

Castle Hill had an existing relationship with Jamal Thorne, a graduate of Morgan State and associate teaching professor of art at Northeastern University, who helped to arrange a connection with his alma mater through his former teacher E.L. Briscoe. Last year, Thorne served as a mentor for the fellows. (Myra Kooy will fill that role this year.) Briscoe hopes that former fellows will return as mentors in the future.

Osborne sees a dual purpose for the residency. On one hand, it benefits Castle Hill: “The more diverse an organization is, the stronger it is,” she says. “Diversity keeps things growing.”

Osborne was further motivated to do something to enrich the creative lives of young African American artists. Distraught over the murder of George Floyd and the continued racism in America, Osborne, whose husband is Black, wanted to make a difference. “My husband and I have the power of making major gifts,” she says. “If I can contribute to causes that assist in lifting up African Americans in this country, I want to be doing that.”

She was also curious: “What happens when you bring a diverse group of artists with completely different life experiences to the Cape? How will this environment influence their creativity?”

Jasmine Adams participated in the first residency last year. “Coming from an inner city, it was a stark change to go from a lot of noise to silence,” says Adams. Like Davis, Adams often creates images of people from her community in Baltimore. At Castle Hill, she immortalized one of her subjects in her largest painting yet.

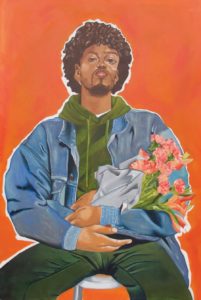

“I was there to challenge myself and think outside of the box,” she says. “I spent copious amounts of time in the studio. Some days I was there for 12 hours.” She created a large-scale portrait of a seated young man holding a bouquet of flowers, painted in a tight, realistic manner with unexpected details like a white outline and one eye depicted as if it’s a collaged element. A straightforward image was transformed into something off-kilter and slightly unsettling.

“It’s not often that people have the privilege to go on a residency right after graduating,” says Adams. “Finding our way is very difficult. This was my first experience where I was being looked at as a professional artist.”

Thinking of the future, Osborne considers the effect the Cape had on several notable abstract expressionist artists in the 1950s. “The influence of time spent on the Cape was an important part of their careers,” she says. “That same thing can happen with these artists. We just need to get more of them coming.”

Fresh Talent

The event: Castle Hill’s Osborne Fellows Open Studios

The time: Thursday, Dec. 22, 4 to 6 p.m.

The place: Truro Center for the Arts, Edgewood Farm, 3 Edgewood Way

The cost: Free