WELLFLEET — Last April, Cole Barash spent three days on the back shore making photographs to accompany a Thoreau-inspired essay by Eileen Myles called A Walk on Cape Cod. During his own walk, he photographed the landscape in stark, almost forbidding images.

At High Head Beach in Truro, Barash used a flash to isolate beach fencing against the dark ocean. It’s a sharp, stylish image. But there’s tension in the path to transcendence: the fence blocks the viewer from entering the inky abyss. Other photos in the series continue the theme. A recently fallen tree hangs over a road in one image; in another, the stripped-down frame of a house sits perilously on a dune.

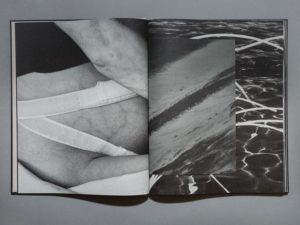

“For the past six or seven years my practice has been largely based in nature and our relationship to it as humans,” says Barash, 35, in his Wellfleet studio — a compact, light-filled structure that he built with a friend. His two most recent photobooks, Stiya and Sound of Dawn, explore the overlapping boundaries between landforms and the human body. “I’m interested in the symmetries and intersections,” he says.

Barash’s journey as a photographer has largely been in settings where contending with nature was a central part of his experience. He grew up in northern Vermont and received his first camera, a Canon AE-1, from his father, who was an amateur photographer.

“I was completely hooked,” says Barash. “I just started shooting everything. This was a way to digest and comment and think through the world.”

He began photographing snowboarders when he was 14. Two years later, he moved to Mammoth Lake, Calif., a snowboarding mecca, with a group of snowboarders who were on the cusp of becoming professionals.

“My parents put the ball in my court early,” says Barash. “I was able to be part of an incredible movement of East Coast snowboarders moving out West. We progressed and grew together. It was a really fun and hardworking time.”

Like his subjects, Barash pushed himself to physical limits in extreme environments. “Those first few years were like 14- or 16-hour days, 15 miles out in the back country, lugging a 40-pound bag,” he says. “You’re really working hard for one photograph.”

At 23, Barash moved to New York. “I had hit the ceiling creatively,” he says. “I just got burnt out, and I knew I needed to go somewhere else.” As a staff photographer for a snowboarding magazine, Barash began to find himself more interested in documenting subcultures than action.

Talk Story, one of Barash’s first projects, was an opportunity to explore surfing subculture. He took pictures of John John Florence, a world-famous surfer, turning his camera inland and focusing on Florence’s life off the waves: moments of melancholy and banality in paradise. Barash captures an unexpected fragility in his subject, a nature-reckoning force who is not invincible.

Barash’s next project took him to another extreme environment. While visiting a friend in Reykjavik, he learned of a small island called Grímsey, 40 kilometers off the north coast of Iceland, on the Arctic Circle, with a population of about 100.

“I got on the ferry with no idea where I’d stay,” says Barash. “I spent 10 days there just roaming around the island, knocking on people’s doors, making pictures of them in their living rooms, having coffee.”

Like his previous project, Barash’s work in Grímsey has a sociological dimension. But the focus here is broader.

“I took a very close and specific look at what makes a place complete: the colors, natural objects, the different faces of people, the types of hand towels people keep in their bathroom,” he says. His images capture the hardiness of the island’s inhabitants: children bracing themselves against the wind, workers in fish-processing plants.

Much of Barash’s work depicts individuals testing their limits of endurance in pursuit of an achievement that often conjures spiritual associations. It’s not surprising that a more recent photobook project, Sound of Dawn, has Barash veering toward abstraction. Photos of landforms in Portugal and Spain alternate with close-up shots of nude bodies. In rich, saturated colors, the combinations create a metaphysical vision where divisions between land and body dissolve.

In his most personal book, Stiya, Barash juxtaposes images of his wife giving birth with photographs of a nor’easter roaring into the Wellfleet coastline: the two events happened within a two-day span. Both land and body are seen at the mercy of extreme, transformative forces, experiences as harrowing as they are beautiful.

Currently, Barash is working on an editorial commission for the New York Times Magazine on health clinics serving people living on the streets in Boston. In his art practice, however, his focus is increasingly personal. His father died in 2020, and since then Barash has been spending days alone in the wilderness making art. “I’m exploring places where my father spent a lot of time,” he says.

This elegiac body of work, titled When the Wind Blows North, resonates with questions of mortality, existence, and memory. As death marks the point at which the body returns to the earth, the landscape becomes a site of memory and a point of connection with the departed. The project includes photographs printed on coils of rope and rice paper that capture the fragile space between spirit and material.

For all Barash’s journeys, he has always returned to Wellfleet, where his family vacationed every summer when he was growing up. By age 12 he was spending entire summers on the Outer Cape. He returned each year for the next decade to work, surf, and build connections in the community. He bought a home here 10 years ago.

“It’s always been a place that felt like home,” says Barash. “We live on a huge eroding sandbar that’s constantly changing. Even if days go by where I don’t really think about it, the tides and the wind are always there. It’s a fascinating place to live.”