The overlapping stories of the Outer Cape are so thick and rich that it’s hard to hear them all: Nauset and Wampanoag people, Viking explorers, Basque fishermen, other European explorers, Pilgrims, whalers, colonial settlers, Bohemians, artists, queers, and more.

Yet geology tells us that west of High Head’s glacial moraine, the land at Beach Point and Provincetown is some of the newest in the U.S., formed by currents, winds, and storms reshaping what the Laurentide Ice Sheet left behind. Only Hawaii, pouring new lava out from volcanic centers, has us beat.

That such new land can hold such old human history is a fascinating conundrum. The Eurocentric tilt of public education taught us to think of New England — Plymouth in particular — as the start of something. I get confused when I think about Provincetown and the Pilgrims.

We know Corn Hill was so named because Pilgrims found cached corn, saved for the coming winter by Nauset people, and took it. We know Nantucketers owed their success to the knowledge of Wampanoag whalers.

Aesthetically, I love the anchor of the Provincetown Monument, completed in 1910, to commemorate the first landing of the Mayflower. But an Indigenous poet friend of mine calls it the “colonial finger” and finds it less than picturesque. I see her point.

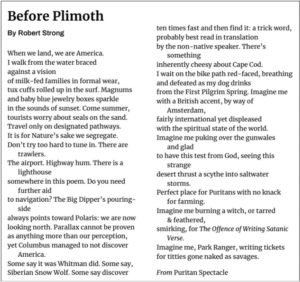

Poetry can play with certainties and jeer and poke at received history. This is just what Robert Strong does in his book Puritan Spectacle, a mashup of history and contemporary riffs on the region.

The title of his poem “Before Plimoth” asks us to consider the whole shebang differently. First: “Plimoth” versus “Plymouth.” Strong puts forth the earlier, more archaic spelling — but with “before”? Before the before? Yes. Strong immediately pulls the contemporary reader into culpability.

The title of his poem “Before Plimoth” asks us to consider the whole shebang differently. First: “Plimoth” versus “Plymouth.” Strong puts forth the earlier, more archaic spelling — but with “before”? Before the before? Yes. Strong immediately pulls the contemporary reader into culpability.

“When we land, we are America.” Is the opening line scathing? Hopeful? Is this past or present? Either way, it’s true: here we are. From this, Strong goes on to engage contemporary Provincetown with all its wealth, glitter, and hedonism. But what I love about his poem is that he doesn’t go down the easy path toward rant. Not fully. Rather, he documents what is: seals, warnings of human-use harm, trawlers, lighthouses, and stars.

Where are we in this fragile land that is one thin edge of the colonial wedge in North America? What does “discover” mean after all? “Some say discover/ ten times fast and then find it: a trick word,” writes Strong. The meanings slip under us.

I adore how time conflates in Strong’s poem. In the end, we see the Pilgrims, the contemporary tourist, the witches tried at Salem, the NPS rangers — all with their own agendas, all echoing what’s come before.

Each year, as the nation celebrates Thanksgiving (and oh, what a beautiful thing to have a holiday that asks us to consider what we’re thankful for), we might also ask ourselves to think about what gratitude erases.