Jack Coughlin’s Golden Cod Gallery has been a Wellfleet mainstay since he and his wife Joan Hopkins took over the space in 1964. The low-lying shingled building stands near a bend in Commercial Street across from Uncle Tim’s Bridge and Duck Creek. The couple, both artists, have used the space to display Hopkins’s landscape paintings and Coughlin’s graphic work — usually portraits and pictures of animals.

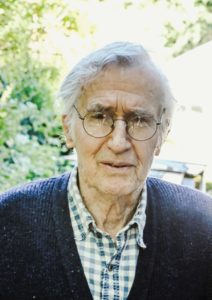

“It’s been a couple of tough years,” admits Coughlin, 90, who says that the gallery has been closed recently due to Covid and other health issues the couple has faced. But Coughlin plans to open it up again next summer.

For those who may have only seen samples of his work at his Wellfleet gallery, a retrospective exhibition now at the Cape Cod Museum of Art in Dennis provides a comprehensive 60-year view of Coughlin’s artwork.

“He deserves to be celebrated as a local master of his craft,” says Benton Jones, the museum’s director of art, who knows Coughlin as a fellow member of the Beachcombers, the Provincetown fraternal organization. Jones would often observe Coughlin at their gatherings “always drawing, always with a sketchbook in hand” — if he wasn’t otherwise occupied playing his harmonica.

Coughlin’s mastery extends across a range of media, including watercolor, pastels, printmaking, and bronze sculpture. But drawing is the glue that holds everything together. “I’ve never wanted to do anything else,” says Coughlin. He has been drawing since he was a child growing up in Fall River and Swansea, and later as an art student at the Rhode Island School of Design. “My motivation is always drawing,” he says.

Drawing is fundamentally about making marks on a surface. In this exhibition, we see how Coughlin is fascinated with the various ways marks can be used to define forms and the ways art materials facilitate this process. The show features Coughlin’s sensuous, delicate pencil studies of female nudes and sweeping charcoal drawings of rhinoceroses in motion.

But printmaking is the territory where Coughlin has focused most of his creative effort. “Printmaking is a great vehicle for drawing,” he says. In a series of woodcut prints done over decades, Coughlin consistently returns to an image of an owl in the woods. In one piece, Winter Owl, marks carved into a wooden board distinguish the form and texture of an owl against a complex tangle of branches.

Other animals appear in Coughlin’s work. In Red Walking, Coughlin uses an etching process to depict a mongrel dog that lived next door to him. Unlike in a woodcut, where the artist carves out the negative space before printing, an etching uses acid to dig out exposed marks on a copper plate, which can then be filled with ink and pressed to create an image. The print exposes the process: the messy plate, dirtied with the residue of ink, and the deep grooves cut with acid introduce an element of violence to the initial drawing. There’s a feral energy in both the technique and the image of the crouching dog.

For Coughlin, technique becomes a means to an end. “I’m interested in movement and life,” he says. “You try to breathe life into what you’re doing and capture the essence of the thing you’re looking at.”

Capturing the essence of animals is a challenge that has continually fascinated him. “I’m crazy about animals,” says Coughlin. “I like the way they move, their structure, and the relation to the way we move.”

In 1965, Coughlin traveled to Europe during a sabbatical from teaching at UMass Amherst (where he continued to teach until the mid ’90s). In Europe, he spent a lot of time in art museums and zoos. According to art historian Maura Coughlin, his daughter and the curator of the current exhibition, these experiences aroused an interest in the “transformative states between human and animal.”

Maura Coughlin, who lives in Eastham and teaches at Northeastern University, organized the exhibition around themes that her father circled back to throughout his practice. The theme of metamorphosis combines the artist’s interest in animals and the human figure. In these works, humans merge with animals in ways both playful and dark. In one Hieronymus Bosch-inspired drawing, a human-fish hybrid devours a person. Another series of etchings depicts animal-headed female figures dancing. And in a pastel drawing, a lobster claw merges with abstracted bodies in a totemic form where elements exist as part of a swirling cosmic whole.

“His imagination was limitless,” says Jones. “His mastery of craft enables him to be incredibly free with his imagination.” Yet the deeply imaginative multi-figure pieces seem to exist as side pursuits: singular portraits of animals and people dominate the exhibition.

As an illustrator for the New Republic, Coughlin created portraits on commission and throughout his life developed a close connection with the artistic and literary scene in Dublin, where he made portraits of writers Seamus Heaney and Samuel Beckett. Beckett thanked Coughlin for his portrait: “I spent a whole morning with him in Paris,” says Coughlin. “He was friendly, saint-like, and very funny — not grim, like his work.”

The range of Coughlin’s work and activity makes it difficult to place him in a specific category. But he isn’t too concerned with being labeled as an illustrator or draftsman or printmaker. “It’s a matter of quality,” he says. “It’s either good or not good.”

One thing that has remained constant is Coughlin’s devotion to making art. “I’ve slowed down a bit,” he says, mentioning a recent hip replacement. But it hasn’t stopped his practice.

“When I’m working, I feel alive,” he says. “And when I’m not working, I feel like something is missing.”

Themes and Variations

The event: A 60-year retrospective of artist Jack Coughlin

The time: Through Nov. 6

The place: Cape Cod Museum of Art, 60 Hope Lane, Dennis

The cost: $10 general admission