Provincetown’s identity is rooted in its history as a place where artists came to develop their vision in a community of creative peers. For many, it also served as their muse.

Depictions of Provincetown form the backbone of an exhibition of works from the Helen and Napi Van Dereck Collection, which is on extended loan to the Provincetown Art Association and Museum. The current exhibition is the fourth since 2020 highlighting work from the collection. Napi Van Dereck, an avid art collector and owner of Napi’s Restaurant, died in 2019.

“He was consumed with the way the town was changing,” says Christine McCarthy, PAAM’s CEO and the show’s curator. “He collected these pictures to preserve the legacy of early Provincetown.” The exhibition raises the question of art’s ability to record history and depict a place truthfully — and the related concern of how our perception of a place is shaped by art.

The paintings, drawings, and prints in the collection were largely created between the 1880s and 1940s and provide a window into Provincetown’s past, glimpses of which can be seen in the present. (In Napi’s own words, the pictures represent “the way it used to was.”)

For anyone with even a passing familiarity with Provincetown’s art history, a walk from the Pilgrim Monument down to Commercial Street is a reminder of the many paintings of its rooftops, a favorite motif since Charles Hawthorne’s Cape Cod School of Art drew artists here in the early 20th century. This slightly aerial view of the town is well represented in the show, most notably in two watercolors by George Yater, who came to Provincetown from Indiana to study art in 1931.

In his works — both winter scenes — Yater uses geometric shapes and the white of the paper to suggest rooftops covered in snow. The jumble of angled flat planes straddles a territory between abstraction and representation. The shapes suggest abstract voids, but their sharp and precise rendering make them architectural elements. This dynamic tension is well realized in watercolor, a medium suited for suggesting illusion while exposing its own materiality.

Blanche Lazzell created her own response to Provincetown rooftops in a charcoal drawing from 1921. The territory here is more abstract and was influenced by Lazzell’s interest in Cubism, which she encountered firsthand while studying with Fernand Léger and Albert Gleizes in Paris. Where Yater’s angled roofs are part of a scene that also includes an icy blue sea stretching beyond the houses, Lazzell’s depiction of Provincetown architecture emphasizes its geometric shapes, an emphatically Cubist vision.

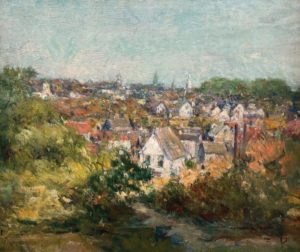

Lazzell’s contemporary Arthur Woelfe represented the town through an Impressionist lens, blending its architecture into a picture dense with marks, textures, and the colors of early autumn. The emphasis here is not on geometry but light. The rooftops are composed of flickering touches of colors, which mix in the viewer’s eyes.

These three pieces underscore how one vantage point of Provincetown can take on different forms through the vision of artists working in varied styles. The artworks don’t provide a static view of a place. Instead, Provincetown becomes an armature upon which the artists develop their own interests and explore the art movements of their time.

A few pieces in the show veer so strongly in the direction of stylization that Provincetown is nearly unrecognizable, as in William F. Halsall’s The Rose Dorothea. It exemplifies the genre of marine painting with its dramatic sky, sharply rendered boats, and waves rhythmically defining the space of the water. But it’s hard to find Provincetown in it — the location could be Holland, or Boston Harbor, or anywhere.

Similarly, Lawrence Grant’s Provincetown Sea Fair recalls a different place with its bluish-green landscape and small crowd dressed in white shirts and flowing skirts. Its Impressionist use of color and imagery recalls turn-of-the-century coastal France — perhaps as a result of the way an artistic style becomes associated with the place where it was conceived. Although elements of Provincetown such as its dunes and the sliver of ocean in the distance surface in the painting, it’s difficult to situate the scene locally. (The difficulty is compounded by the now-forgotten event it depicts, which the artist renders with fantastic flowing banners.)

Some elements of the town in these views remain unchanged, like its rooftops and wharves. But several paintings depict Provincetown’s industrial past, now largely replaced by tourism. Samuel Brecher’s painting of a railroad crossing is a scraped-down, gritty surface where shades of brown and gray depict an urbanism we no longer associate with Provincetown.

Other artists turned their attention to the fishing industry along the shore. In one of the many drawings in the show, Betty Waldo Parish depicts burly men cutting fish and emptying barrels in a fish processing factory, an image that nods toward social realism. Along similar lines, Sol Wilson’s standout painting shows fishermen working on the docks, their blocky figures outlined in kinetic lines and rendered in saturated, tonal colors. The picture, which feels both sensitive and rough, recalls the work of Marsden Hartley.

Another gem in the show is a small hand-colored lithograph by Dorothy Lake Gregory. Gregory first came to Provincetown to study with Charles Hawthorne but wasn’t terribly impressed with him, writing to her father that the towering figure “uses fearfully bad grammar and is a flirt.” She remained on the Outer Cape after marrying the painter Ross Moffett and concluded that “you learn more just from keeping at work than you do much from any teacher.” This independent streak is evident in her depiction of Provincetown.

Gregory renders the town from a high vantage point and focuses on its rooftops and the harbor beyond, like several other artists in the show. But she largely disregards rules of perspective. Her off-kilter lines and the serpentine limbs of trees create a fairy-tale space populated with swirling butterflies, a man riding a horse and buggy, and other animated details, all rendered with a miniaturist precision. The town seems to flow into the harbor, which has some details unique to Provincetown. But Gregory takes ample imaginative liberties in her depiction.

Like many other works in this exhibition, this is a painting of a place that exists simultaneously in the past and the present: something both recognizable and obscure. Ultimately, it represents the artist’s own vision with a subjective connection to its subject. This show proves Provincetown is a slippery muse, malleable and shape-shifting: a multifaceted vision that parallels the life of the town itself, an ever-changing place of reinvention.

Painting the Town

The event: The Napi and Helen Van Dereck Collection: Part IV

The time: Through Oct. 30

The place: Provincetown Art Association and Museum, 460 Commercial St.

The cost: $15 general admission