Many people dream of quitting their jobs to become painters or writers, musicians or playwrights. The prospect of no regular paychecks — and no guarantees — can be frightening. But for those who want it badly enough, it can be done.

John Clayton did it.

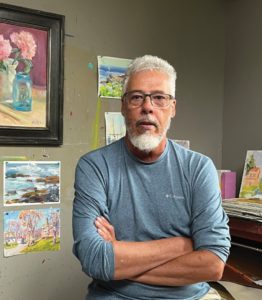

Clayton is a painter who makes his living by selling his work and teaching classes at the Provincetown Art Association, the Cape School of Art, and the Chatham Creative Arts Center. He is a familiar sight around Provincetown, where he has lived for 30 years. He can often be found by the side of a road with an easel in front of him as he paints the view through a row of houses.

He can also be found leading plein air painting classes, as he was doing one day recently on the beach behind Angel Foods. A group of students were facing the pier across the bay. Clayton went around the class asking questions and making suggestions: “Too dark here,” he told one student. “Try moving this over there,” he told another. The students kept working and reworking under Clayton’s watchful eye.

Though the students are here to learn about color, Clayton has them start painting in black and white to first capture light values. He tells them to divide their canvases horizontally and do their monochrome rendering on top before they shift to color in the lower half.

“Two things determine the light,” he says, brandishing a roll of paper towels. “The sky and the sun.” On sunny days the sky is warm, and colors shift towards that warmth. On cloudier days, the colors cool. He holds the paper towels high to illustrate, and the white takes on warm tones. When held closer to the shadowed ground, the color becomes faintly blue. With such simple gestures, Clayton teaches his students to see the subtle colors in everything.

“I learn from my students,” he says later in his studio. “It’s not just a way of supporting myself.” During the pandemic, he taught weekly Zoom classes. “I’d ask myself what I wanted to learn. Say it was folds, if I’m lousy at folds. So, I read everything about folds, throw it into my head, and paint a mockup. Then I’d go and teach that.”

Clayton speaks of the importance of always challenging ourselves — to find our weaknesses, take chances, and not be afraid to fail. “Students like it when you fail a little,” he says. “Then you’re human.” He laughs, which he does often as he talks about life and art.

He’s predominantly devoted to working outdoors and paints in the impressionist lineage of Charles Webster Hawthorne and his Cape Cod School of Art. Henry Hensche learned from Hawthorne; Lois Griffel and Hilda Neily learned from Hensche. And Clayton studied with them.

Learning to understand Cape light is a central part of Hawthorne’s tradition, and Clayton believes the sand dunes that edge Provincetown add to the unusual quality of its light. “Because of all the sand dunes, the light bounces back into the sky and is reflected back down onto the water,” he says. “The combination of those three things — sun, sky, and water — make it brighter here.” That changes the rules of conventional painting: “In painting, the sky is usually the lightest thing. But sometimes that’s not true here,” he says. “Sometimes it’s the darkest thing and causes the white of a boat to pop against the sky.”

Clayton becomes animated when he talks about color and light. He says he always tells his students that learning how to paint is not about selling a painting. “That’s the job of it,” he says. “The real soulfulness is what you see and how you see. Seeing heightens our awareness. I dream in color now. I never dreamt in color before.”

Clayton originally set out to be an actor until a scene partner (who also happened to model for art classes) told him to check out the Art Students League instead. So, he went and began studying art. Then someone else told him he should go to Provincetown because it was “perfectly affordable.” (He laughs at how different things were in 1994.)

“I didn’t really love the paintings of the Cape School at first,” he says. “I didn’t see color that way. But I got a job as a waiter and lived at the school in the barn. I began to understand a little more about color. Then I was hooked.”

After spending a few summers in Provincetown he moved here and has lived and taught in town ever since. He has discovered that being a full-time painter has its rewards.

“When I get up in the morning I don’t think, ‘Oh god, I have to go do this,’ ” he says. “Most days I get up thinking, ‘What should I go paint?’ ”