Federal Hill, a restored antebellum plantation house in Bardstown, Ky. better known as the Old Kentucky Home, opened its doors to statewide fanfare and a throng of visitors on July 4, 1923, following a three-year campaign for its purchase and renovation. It was Kentucky’s first historic home — and one of the first projects to capitalize on 20th-century white America’s fervor for automotive tourism and Old South nostalgia. Federal Hill quickly became the state’s tourist hub.

Why this house? Because, according to Federal Hill’s promoters, it was here in 1853, in the family home of former U. S. Sen. John Rowan, that Stephen Foster, the father of American music and a Rowan cousin, wrote “My Old Kentucky Home.” Soon after, the Kentucky General Assembly named the song the state’s official anthem.

Visitors to Federal Hill were shown the “Foster Secretaire,” a desk at which cousin Stephen was said to have composed his classic rendering of a Black man’s longing for the Kentucky home that “hard times” led him to leave, a place where “the sun shines bright” and “the darkies are … all merry, all happy, and bright.” They were told that Foster’s song was inspired by his observing the contentment of the people enslaved there — a narrative reinforced by the presence of a genial elderly Black man who sat outside the house playing Foster tunes on the harmonica. He was billed as the son of one of the Rowans’ loyal domestics.

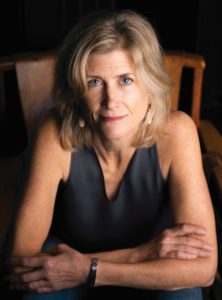

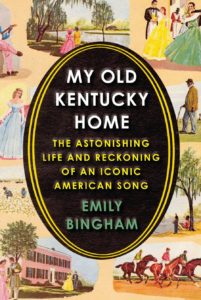

As Emily Bingham reveals in her brilliant book My Old Kentucky Home: The Astonishing Life and Reckoning of an Iconic American Song, every detail of this narrative was a lie.

The Pittsburgh composer Stephen Foster never set foot in Bardstown or knew the Rowan family, and the “Foster Secretaire” was likely purchased for the St. Louis World’s Fair in 1904. Bemis Allen, the harmonica player, had no prior connection to Federal Hill before being hired to play the role of “the colored minstrel” there, as a 1930 feature in Kentucky Progress Magazine described him. Early tourists noticed that Federal Hill lacked the “little cabin” where the young folks frolicked in Foster’s song, so the curators constructed a cabin-like gift shop and passed it off as the former slave quarters. The actual Rowan slaves had slept on the dirt floor of their enslavers’ basement.

“The real Kentucky home of the enslaved,” Bingham writes, “was shot through with violence — rape, assault, deprivations of all sorts, the disregard for family ties — and the constant threat of all these.” Her book is a searingly honest effort to correct our nation’s continuing “disconnect between history and fantasy” in matters of race.

Stephen Foster, who died in 1864, was not responsible for the inauthenticity of Bardstown’s Old Kentucky Home. But his music was an early agent — and, after his death, a principal vehicle — not only of the “toxic illusion of contented bondage” but of the entire cultural repertoire of dehumanizing stereotypes of Black personhood by which white Americans entertained themselves and, in Bingham’s trenchant phrase, “learned to feel all right about racism.” The narrative of that enduring cultural history and its “incalculable social and human damage” — a history in which the Federal Hill fantasy is just one episode — is Bingham’s stunning achievement.

Raised in a downwardly mobile Southern-sympathizing family and reaching his mid-20s with a drinking problem and a wife and child to support, Stephen Foster turned his talent to writing for the most influential and lucrative American entertainment medium before Hollywood: the minstrel show. There, white men in blackface performed skits, songs, and slapstick routines in faux “Negro dialect” that depicted Black people as “uncivilized, inane, emotional, crude, overly sexual, but also ‘naturally’ musical and athletic,” Bingham writes. Working for blackface impresario E.P. Christy, Foster wrote contented slave songs for Christy’s Minstrels, including “Oh, Boys, Carry Me ’Long,” “Old Folks at Home,” and “Poor Uncle Tom, Good Night.”

But Foster also aspired to produce music suitable for the genteel white parlor, so he revised “Poor Uncle Tom,” removing the dialect, adding the “Weep no more, my lady” chorus, and retitling it “My Old Kentucky Home, Good Night.” These changes allowed the song over time to become an icon of “generalized white American middle class sentiment, sentiment that almost wholly bypassed both the politics of slavery and actual ‘Black feeling,’ ” writes Bingham.

Actual Black feeling, the author shows, was precisely what American popular culture was designed to suppress or falsify — from Christy’s Minstrels to Gone With the Wind (which features 11 Foster tunes) to the reverent ritual singing of “My Old Kentucky Home” at the start of each Kentucky Derby. After the Civil War, for almost 100 years, Black musicians and vocalists could sustain careers only by performing music that “validated plantation fantasies” and “whitewashed [their own] historical nightmare.” Many, out of necessity or “the hope of progress,” acceded and, with every sentimental note, delivered the “profoundly inauthentic message” that white audiences wanted to hear: “that they too were nostalgic, not insulted, hurt, struggling, and furious with the forces thwarting racial uplift,” Bingham writes.

When, in 1914, Black parents and the NAACP objected to a popular public school music anthology, Forty Best Old Songs, seven of which contained overt racial slurs, they were pilloried in the national press as hypersensitive malcontents, defamers of the “precious musical heritage of our people as a whole.” And when, 55 years later, Black University of Louisville students marched to the slogan “The darkies are not gay any longer” to protest Churchill Downs’s insistence on displaying — and encouraging Derby patrons to sing — Foster’s original lyrics, the backlash was much the same. Only when some corporate sponsors of Derby broadcaster CBS began to balk in 1972 did track administrators quietly replace “darkies” with “people.”

The life of Foster’s song that Bingham traces is truly astonishing in its reach. It obsessed the pharmaceutical magnate J.K. Lilly in the 1930s; it traveled the world with U.S. armed forces in the 1940s; it Westernized Japan with KFC’s Col. Sanders in the 1970s; and, in the 1980s, it sealed Toyota’s selection of Kentucky as the site of Japanese industry’s largest-ever American investment.

But Bingham reveals another more personal echo of this American song: its incitement of her determination to “confront what is underneath” the culture that shaped her. The story of “My Old Kentucky Home,” she writes, is also hers, a story of “a privileged white Kentuckian descended on both sides from people who owned people,” and whose 20th-century forebears, progressives in every other respect, “never washed away the deep, dark well of white rage that persists even within the educated, the genteel, the liberal-minded.” It is the story of someone who grew up, and teared up, singing that nostalgic song at the start of each Kentucky Derby — until she confronted what was underneath.

Bravely, Emily Bingham writes the story of Foster’s song partly as autobiography. But not hers alone. It is ours as well, America’s cultural autobiography, and Bingham challenges us to recognize it as such — as a legacy that we must frankly own before we ever shall overcome.

The Dark Side of an American Song

The event: A talk by author Emily Bingham on My Old Kentucky Home

The time: Wednesday, Aug. 10, 7:30 p.m.

The place: Wellfleet Public Library, 55 West Main St

The cost: Free