Lauren Ewing is wearing a narrow pin that she designed and fabricated. In lower case, it reads “everything speaks.”

“My art is all about the world that we live in, and all of the natural world is speaking to anyone who can receive,” she says. Hydrangeas are in full bloom outside her front door.

But the pin’s message also refers to art, she says: “Humans don’t make anything that does not speak.”

Ewing’s studio in Provincetown’s East End is sequestered from the expanse of water and sky that pulls creatives to the Outer Cape. Anchored by a workspace with tiny sculptures, mostly of hands, the studio exudes activity and the pleasure of making.

Ewing is a philosophical artist who relishes what the human hand can do. Humans are makers, she says, naming the handmade objects, from tractor parts to pies, that represented “material culture” on the Midwestern farm where she spent her childhood.

Being a maker is in her blood; she asked for and received her first set of oil paints when she was eight. Her work has been shown at the Schoolhouse Gallery in Provincetown and in New York City, Germany, Denmark, London, and Australia. It is in the collections at MoMA and the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Ewing is perhaps best known for the 9-by-9-foot Provincetown AIDS Memorial sculpture, constructed of 17 tons of Tuscan marble, on the east lawn of town hall. “Remembering” is inscribed on two sides. This symbol of the AIDS epidemic and the efforts of caregivers who ministered to the sick and dying was dedicated in 2019. Ewing carved the top surface, with its watery ripples, to represent “a quiet tide under a full moon,” she says.

Ewing is not just a sculptor. A show of her paintings is at the Schoolhouse Gallery through Aug. 10. Gallery director Mike Carroll first heard about Ewing from her sculpture students at the Fine Arts Work Center. “She paints like a sculptor,” he says.

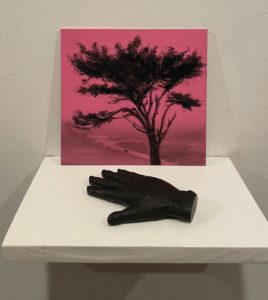

The exhibit’s title, “Startling Beauty and Anomie,” points to Ewing’s two suites of paintings, four each in two sizes, 30 by 30 inches and 5 by 5 inches, on coated board. Some of these paintings began as photographs of the Pacific Coast and Alaska’s Inner Passage. There she photographed, at dusk, a bank of pine trees.

The paintings are all about those trees and others — and the black swans that appear in each of Ewing’s paintings as tiny solitary beings.

Ewing first toned the suites with acrylics and oils. Each uses the same basic colors: blue, yellow, green, and pink. The trees and atmospheric effects were created with her fingers, using black soot.

The imagery in each painting is punctuated by the single black swan seeming to float calmly by; the eye searches for the long-necked dark fowl. In these paintings, the swans rest on water that is still. Yet in literature and film, black swans warn of underlying fractures and the loss of social cohesion and shared beliefs.

Ewing’s art captivates a viewer’s senses through color, shape, and texture. All the works are unsigned; Ewing wants them to speak for themselves. “The artist’s hand is in the work,” she says.

Ewing is fascinated by the ways in which the body is present in an artwork. She describes the moment when, as a young faculty member at Williams College, she instructed students to look closely at a work by Jackson Pollock. They detected one of the artist’s beard hairs in it.

In a work of art, it is physical gestures that bring the body into play. Ewing raises her arm to the level of a large blue painting to demonstrate the process of making these striking, minimalist images. With hands and fingers, she strokes and massages the shadowy trees in the background and the darker tree in the foreground, creating, she says, “density and presence.”

She demonstrates the ways her fingers smooshed very fine carbon black soot onto the fine-grained, toned board. Hence the characterization as finger painting: the seasoned maker returning to basics. Didn’t we all begin with finger paint?

The exhibit’s title references English painter J.M.W. Turner, as he is popularized in the bad-boy docudrama Mr. Turner. The delicious and likely apocryphal cinematic moment comes as Turner, competing with a rival also showing in the National Academy, reaches over to his seascape and, using fingers and spit, transforms his painting.

As Ewing demonstrates her soot-and-finger technique, the reference to Turner becomes clear. Ewing, too, has emerged from the shadows: through her, nature and our original natures as makers are given voice.

The four smaller “Black Swan Fingerpaintings,” also made with black soot, were originally created as studies for the larger works. Displayed in a compact grid, two over two, their compression seems to tug outward, radiating a distinctive power.

Each painting is paired with a miniaturized replica of a hand, cast in bronze or silver. These would fit into the center of the palm, creating, if handled, a warming sensation.

“I needed to remember the body in the world,” Ewing says. “The body is everything, where we begin and end. And we can’t forget touch, which is what these paintings are about.”

“Breathe In and Breathe Out” is the name of the series Ewing is thinking about now. To paraphrase Marsden Hartley, who walked the Provincetown streets and palled around with actors and painters in 1916, when the Provincetown Players were getting started, “Just wait until you see what I do next year!”

Finger Painting

The event: Works by Richard Klein, Lauren Ewing, Jason Rohlf, David X Levine, and Tess Michalik

The time: Through Aug. 10

The place: The Schoolhouse Gallery, 494 Commercial St, Provincetown

The cost: Free