The densest thing about “Density’s Glitch,” the current show at the Fine Arts Work Center (FAWC), is the accompanying text. Just a page in length, it has some knotty phrases. I’m still pondering the first sentence, which explains how the exhibition deals “with the lingering and fluid shapes of time that a glitch aesthetics produces.”

Although contemporary art and its accompanying texts are opaque to many, this show proves that, if you give them some time and attention, they can speak powerfully to our present.

The artists in this exhibition are former FAWC fellows, each of whom spent seven months living and working in Provincetown at different points in the residency’s history. The exhibition provides a snapshot of the contemporary art world in which many of these artists have built careers since their time in Provincetown.

The exhibition’s curators define a “glitch” as an “unexpected discontinuity in transmission, a shredding of circuit.” It’s a break in the system, both “a failure and opportunity.” Glitches show up in our culture all the time. Social media algorithms, even when working correctly, are glitches in a way, turning what was billed as a utopian space for human connectivity into a space where corporate interests rule, fake news proliferates, and the flames of conflict are fanned everywhere from ethnic fights in Myanmar to schoolyards across the country.

The understanding of gender in our culture is also proving to be glitchy, as notions of gender expression and identity continue to expand. The curators celebrate this expansion, referencing ideas from Legacy Russell’s book Glitch Feminism. “This glitch aims to make abstract again that which has been forced into an uncomfortable and ill-defined material: the body,” writes Russell.

In line with these ideas, the exhibition stakes its territory in concerns of abstraction and the body. Much of the work in this exhibition deals with structure and its disintegration or reappropriation. The artists don’t offer solutions. Rather, they provide a reflection and an alternative — something “sensuous, experiential, and confrontational,” according to the exhibition text.

Wilder Alison’s abstractions represent a core tension at the heart of this show.

Her paintings, created from dyed wool and threads, embody a friction between the rigid structure of sewn stitches, which hold the piece together, and a dissipating abstract image. The colored dye bleeds into the fabric, imperfectly trying to convey a geometric form. It’s a sensuous counterpoint to the definitive order and geometry of the stitched lines.

In the rear gallery, Nadia Ayari and Sarah Peters also complicate notions of power and order in their work. Peters’s sculptural bust Brutalist evokes Greek and Roman rulers. In her work, however, the eyes are hollowed out, the person stripped of personality. She obsessively renders the figure’s hair, celebrating eccentric tactility rather than a powerful personality.

Like Peters, Ayari works within a pared-down visual vocabulary. Her painting Scaffold VI features a stylized, repeating leaf with a branch diagonally cutting through the image, which is lined with blood-red strips of paint. There is a severity in the simplicity and structure of the composition. Like Peters, she subverts the seriousness of her image with a fetishistic interest in surface and materiality, her image slowly built through an application of viscous marks of paint.

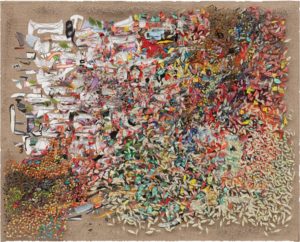

Elliot Hundley’s piece shows a similar curiosity about tactility and systems of order. Hundley, one of the show’s most well-known artists, typically uses collage materials to create meticulous and sumptuous visual universes. His piece, although smaller than most of his work, is no exception. Here, he uses pins to affix bits of colored plastic and paper to a canvas; they hover over a collaged surface of magazine images. The density of marks and the precision of their placement suggest a system or order, recalling schools of fish or bacterial growth. On the edges of the surface, some pins sit waiting for use.

It’s a busy piece, with flickering movement, but all this activity serves no practical or scientific objective. It exists for pleasure, much like Austin Ballard’s nearby sculpture, in which the artist uses woven cane webbing, a methodical craft process associated with furniture, to create a nonfunctional object.

At first glance, Bridget Mullen’s painting reads abstractly. But a careful look reveals cartoonish eyes hovering in a grid-like space. Geometric shapes at the bottom of the painting recall early computer games, and lines snaking up to the top of the painting suggest a network system. Is this a landscape of a virtual, digital space? The figure seems lost, melting into a nonhuman reality.

The show features other shape-shifting figures like Mullen’s. Troy Michie’s melancholic collage, ostensibly about loss and desire, features three figures, all partially obscured. One is represented as a cutout form, a negative space hovering over a photograph of a man.

Autumn D. Wallace’s nude figures also dissipate, the borders of their bodies ambiguous and subsumed by the painting’s sensual atmosphere. Geoffrey Chadsey’s unsettling, eerie drawings echo the curators’ statement about “embodiment as a liminal realm.” In his pieces, the human form undergoes radical transformation. One figure has three sets of eyes; another’s face is covered in fur.

The curators locate these imaginings in the space of contemporary sexual and gender politics, yet the artworks also address a persistent concern within art to transcend one’s bodily limitations, a theme arising in places as diverse as religious medieval art and Shakespeare’s plays.

Angela Dufresne, who curated the show with Cash (Melissa) Ragona and Andrew Woolbright, has a chaotic multi-figure painting in the exhibition. It’s unclear what is happening, but there seems to be a breakdown of social order. Most people are sitting on the floor; someone stretches in the middle; a woman sits on a table at the front of the group, facing them. Is she a professor trying to maintain order? Despite the disorder, there’s a congeniality and sense of freedom in the group and an aesthetic joy evident in the making of the painting.

The show presents artists working amid a breakdown of order, not unlike the setting of Dufresne’s painting. Their stance is varied, some responding to the current moment in celebration, others in defiance, others prophetically. The curatorial text quotes Lauren Berlant describing the glitch moment as “an active space in which we try out tentative forms.” Here, artists are doing what they have always done best, inventing new forms and filling the space of change with dense images of material richness, both reflecting the culture and defining their own reality.

Unexpected Discontinuity

The event: “Density’s Glitch,” a show of works by former FAWC fellows

The time: Now through Aug. 28

The place: Hudson D. Walker Gallery, Fine Arts Work Center, 24 Pearl St., Provincetown

The cost: Free