Strolling down Commercial Street and into the Mary Heaton Vorse house, one is aware of Provincetown Harbor moving in and out of view. It glistens between buildings or stretches out to the horizon from the house’s second-floor windows. Encountering Joel Janowitz’s artwork on the walls of this historic home-turned-cultural institution brings the image of the water inside, in a fitting union of subject matter and setting.

Janowitz typically works in series, and the watercolors, prints, and oil paintings on display belong to bodies of work featuring water, including plein air paintings done on the Outer Cape in the 1970s and more recent images of lifeguards, divers, and a seaside pool in Australia.

While he was a student at Brandeis University, Janowitz flip-flopped between art and psychology before emerging with a psychology degree. After graduating, he pursued art but never stopped considering psychological perception.

“I think about the interaction between one’s interior space and what we’re perceiving outside of us and how to make that tangible in some way,” Janowitz says.

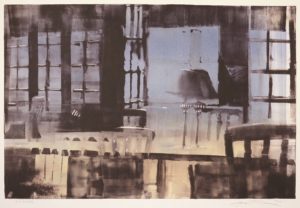

On the walls at the Vorse house, in two monotype prints of the landscapes viewed through interiors, Janowitz plays with these notions while introducing a similar tension between abstraction and representation. Both images are from his experience painting at the Maine home of Fairfield Porter, the 20th-century painter of breezy, light-drenched landscapes. On a visit to Great Spruce Island 25 years ago, he met Porter’s niece and has returned nearly every year since, staying for a week at a time with artist friends.

In Across, Janowitz represents the landscape abstractly as light and color with no discernible natural forms aside from a hazy division between water and sky. In the foreground is a table and chairs, providing solidity. A gridded stretch of windows defines the middle ground, in which a lamp dissolves into the landscape. The interior is simply a vantage point, reflecting the viewer’s relationship to the scene.

Forms veer in and out of focus in this piece and in Old Books, a monotype from the same series. Here Janowitz hastily depicts Porter’s collection of books. Loose gestural marks cut into the foreground, and a landscape looms in the background as a source of light. Curated by Gene Tartaglia, it’s a well-placed piece, hung against a bookcase, highlighting books as a point of connection between Janowitz and Porter and echoing the connection between the viewer’s space and Mary Heaton Vorse. The piece conjures memory, the image foregoing concrete, objective description in favor of something more elusive — perhaps an emotion, a fading recollection, or a relationship with someone departed.

Janowitz began as an abstract painter and explains that “I have kept abstraction with me in how I think about painting.” Two significant painters with whom he studied at Brandeis, Michael Mazur and Philip Guston, also moved between abstraction and realism. Mazur was working figuratively when Janowitz was his student, creating psychologically charged portraits, but ended his career working more firmly in the territory of abstraction. Guston moved the other way, from abstraction to figuration.

“I think it was a frustrating time for his work,” Janowitz says of the period when he studied with Guston, who was then on the verge of developing his groundbreaking figurative work. “I think he was searching for something that wasn’t quite there. What I got from him was a willingness to push beyond what’s comfortable in one’s work, to really challenge oneself, and to not know what something’s going to be and find that out from doing it.”

Janowitz’s works, spanning both floors of the Mary Heaton Vorse house, reveal this openness to process and discovery. He favors watercolor and monotypes because of the unpredictability of the materials. With monotypes, “You never know what you’re going to get,” he says. “It’s a medium that encourages a certain kind of spontaneity because you only have a few hours to work.”

He describes watercolors as taking on “a life of their own,” and “in both cases the limitations of the medium are a tool to break you out of what you might have thought that you wanted to do, but really wasn’t such a good idea anyway.”

Often, he combines the materials. A monotype of swimmers on a raft in the upstairs bedroom is one he cast aside for years before injecting new life into it with lush strokes of watercolor.

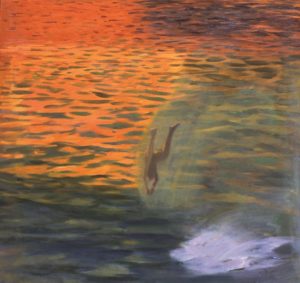

In the main room of the house, Janowitz shows two series, one of lifeguard drills in the ocean and another of swimmers jumping into a Gloucester quarry. In Rescue, a group of lifeguards emerge from rough surf diminutized by waves and the expanse of ocean. The speed and spontaneity of monotype is at play in the way Janowitz creates the crashing waves, wiping away paint in hurried gestures, echoing their movement. A nearby watercolor, Ready, reveals a similar synchronism between material and subject matter. In this image, Janowitz’s washy, wet-on-wet use of the material aptly describes the still ocean on which sit four lifeguards looking out at the horizon.

Janowitz’s images of lifeguards and quarry jumpers conjure slightly ominous feelings. The lifeguards wait for danger, and the absence of sky in these images leaves no way out. Janowitz relates these pieces to the threats of climate change and rising sea levels. Likewise, the jumpers can be read as both terrifying and freeing, he notes. They are in free fall, and it is up to the viewer to fill out the narrative as a moment of either joy or despair.

The selection of beach paintings in the dining room of the Vorse house are lighter in feeling. These small plein-air paintings are visual gems, revealing a keen sensitivity to touch and light. They reveal hints of their time, such as a topless sunbather or yellow lawn chair. Janowitz painted them on the Outer Cape in the 1970s, and unlike his newer large oil paintings, these pieces flicker with openness and spontaneity.

“That’s another process that’s so complicated and changing all the time as the weather changes, as the time of day changes,” Janowitz says of works made on the beach. Painting them, he says, “was another freedom for me.”

Janowitz’s works are on display in Provincetown in this exhibition and in two simultaneous shows at the Provincetown Art Association and Museum and the Schoolhouse Gallery.

Joel Janowitz and Friends by the Sea

The event: An exhibition of paintings and prints by Joel Janowitz and others

The time: May 27 to July 10, Wed. to Sat. from 10 a.m. to noon, by appointment: please email [email protected]

The place: Mary Heaton Vorse house, 466 Commercial St., Provincetown

The cost: Free