When I was a kid, history class bored me. It was all dusty, musty dates, laws, and names. I have a hunch I’d have been more interested if I’d been able to read poems about the Salem witch trials, Lewis and Clark, or World War II. But books like Nicole Cooley’s The Afflicted Girls or Frank X Walker’s Buffalo Dance: The Journey of York or Brian Komei Dempster’s Topaz did not then exist.

Many contemporary poets are building bridges of connection to the past, enlivening it with imagination and empathy, helping readers consider how the present echoes with what’s come before. That poets often root for the underdog, raise an eyebrow at received wisdom, or chip at the surface of convention sparks the work. After all, it’s fun to play the contrarian or shine a light on the overlooked.

John Bonanni’s searing poems about AIDS in the 1980s are part of that trend and of a larger groundswell of art, literature, and film looking back on that era. Why now? Because it takes time and distance to understand the larger patterns that trace through our experiences. As Masha Gessen wrote in a 2018 New Yorker article about the Provincetown AIDS memorial, that stone sea beside town hall, “A line separating the past from the present is essential for memory to begin forming.”

Perhaps enough years have passed that the pain is less acute, permitting perspective. The fear that such a significant time could fade from our memories, be glossed over or forgotten, also spurs new reflection.

John Bonanni was not among the community members or care providers who lived through the AIDS crisis on the Cape. But he inherited that history, and his poems seek to understand both the moment and its legacy.

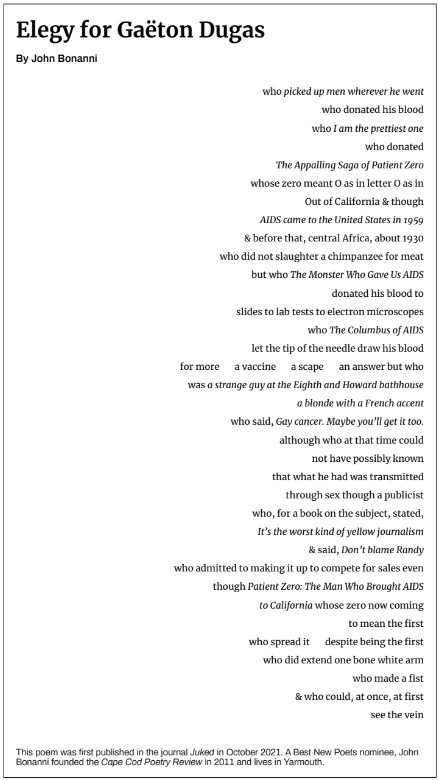

Gaëton Dugas, the subject of this poem, was a flight attendant and early AIDS victim who died in 1984. He was also falsely named “Patient Zero” by Randy Shilts (the Randy of the poem) who wrote And the Band Played On. In fact, studies labeled Dugas “Patient O,” indicating “Out of California,” not “Zero.”

While it’s true that Dugas had HIV and may have transmitted it before the virus was understood, in 2016 researchers examining blood samples from that time found that he was not “the Columbus of AIDS,” as he was called by the National Review in 1987, a notion Shilts amplified in his book. HIV had been present long before Dugas’s infection. And he had done his part to try to help fight the disease by volunteering to participate in medical studies.

All of this is in the poem, presented with an ear to music and a mind tuned to irony. Made vivid, surprising, and heart-wrenching.

What poems about history offer is a way to connect mind and heart — what we know and how it might have felt then and how it moves us now. It must have been awful to be wronged in the way Gaëton Dugas was: accused of bringing AIDS to America when he was trying to help researchers find a cure by sharing his story and his blood.

In Bonanni’s poem, italicized phrases indicate words taken from interviews, article titles, and other sources. These moments remind us that Bonanni’s subject is not invented.

It’s worth noting the poem’s typography, too: not many poems are right-justified. To me, this choice illustrates Bonanni’s desire to have us consider the subject at hand from another perspective.

In Bonanni’s poem we see the many selves of Gaëton Dugas: world-traveling French-Canadian, exuberantly sexual, vain, altruistic, a scapegoat. Don’t we all, as Walt Whitman wrote, “contain multitudes”? Bonanni allows us to see how currents move through Dugas, how we “see the vein” of history flowing through a man’s body.

June will be Pride month, a time to celebrate the freedoms that have been hard-won in the LGBTQ community, to prance and flounce and rainbow it up, a time to think about how to support the people, young and old, who are living in repressive and potentially dangerous communities. Poems like “Elegy for Gaëton Dugas” allow us to trace our history, to remember the lives that shape the moment we live in today. It reclaims a person cast as a pariah. It inspires me to think what other figures might be revived with complexity and grace.