Ukraine, Covid, the GOP, the radical right’s takedown of the Supreme Court — take your pick, or feel free to add your own favorite bogeyman that keeps you up nights. Given the state of the world today, maybe the only thing that gets us out of bed in the morning is hope. Hope got us through 2008 with Shepard Fairey’s poster of Barrack Obama, and Rowland Scherman’s photographs, on view until June 26 at PAAM, give us another needed booster shot.

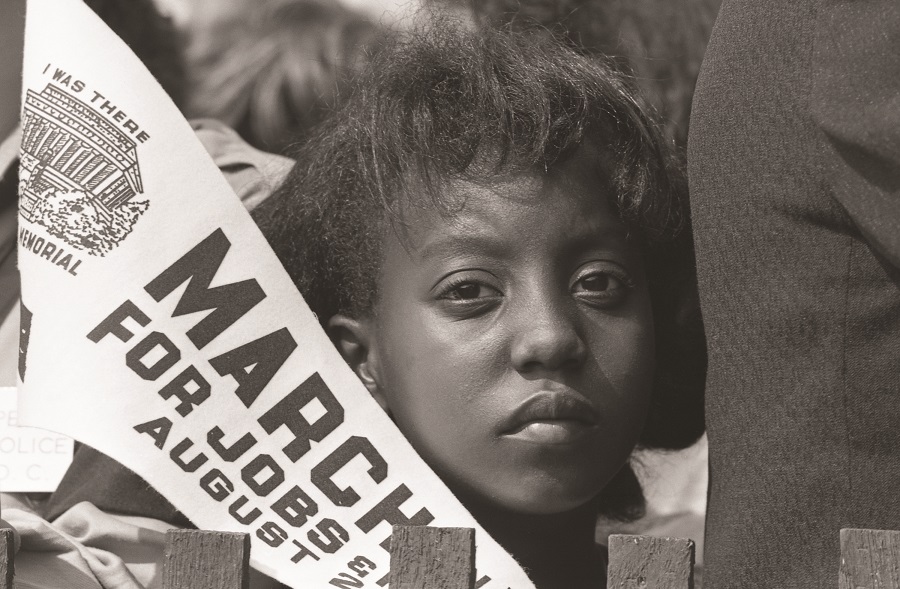

Scherman lived and worked primarily during the 1960s and ’70s, disruptive times reminiscent of today. He could have focused on the darkness: Southern police officers siccing dogs on Black demonstrators, or the drugs and carpetbagger record executives that infiltrated Laurel Canyon. Instead, he showed the world what dignity and fortitude looks like in his images of the march on Washington in 1963, and the innocence that still prevailed in the California music scene with Joni Mitchell and Judy Collins sitting together in a tree house.

Scherman portrayed the strength, resilience, joy, and beauty the human race is capable of, and isn’t that something we need to be reminded of now? How sometimes seriously flawed human beings — think of JFK and the contrast between Camelot and Vietnam, for example — could still manage to make the world a better place.

Scherman became the first Peace Corps photographer in 1961. A debonair young man with a pipe is what he looked like. “That’s what I hoped I looked like,” he says. “Determined” is how he describes himself.

“Like jillions of other people,” says Scherman, “I was bowled over by Kennedy’s speech about asking what you could do for your country.” Legend has it, and he says it’s true, that he found the name of the Peace Corps public relations person, took a bus to D.C., barged in on the nascent organization, something that you couldn’t even think of doing today, and said, “Here I am. I’m Rowland Scherman. I’m a photographer.”

“I wasn’t a photographer,” he says now. “I was taking pictures of out-of-work actors in the Village. I didn’t know much, but I knew I wanted to do something.”

“We don’t need a photographer, kid,” was the Peace Corps official’s response. Actually, they did need a photographer — they just didn’t know it. And because Scherman stuck around, he ultimately was given an assignment that led to access to some of the most historic political and cultural events of the time.

That job was the start of a career that saw his pictures of some of the most celebrated people of the era published in Life and other magazines. “I know I’m a good portraitist,” he says of the secret to his successful career. Portraits are pretty much all he does. Try finding a landscape by Rowland Scherman. “They’re around,” he says. “Maybe in the basement.”

His pictures always reveal an engagement with the subject, even during sublimely intimate moments when the subjects are seemingly unaware of Scherman, like the shot of Arthur Ashe doing his laundry, or Mississippi John Hurt sitting on a bed, playing to a little boy.

Scherman, who turned 85 on April 30, is a wonderful storyteller, still very much engaged in the world. He’s keen on the iPhone, what its camera is capable of producing, and how it’s given everyone the ability to be a photographer. It’s easy to see that his images are as much a result of his personality and curiosity as his technical ability.

Passion and duty to country motivated Scherman to get on that bus to the Peace Corps office, but still, he was young and needed money. Was making photographs a political act for Scherman?

“Most of the time, I’d like to say it was; most of the time it was a job, it was paying the rent,” he says. “It was maybe growing into an iconic lensman like some of the people I was dealing with when I was a darkroom flunkie at Life magazine: the great Gordon Parks, and of course [Alfred] Eisenstadt. These Life guys weren’t even my favorites.”

Scherman says his list of favorite photographers changes, but always includes Jacques Henri Lartigue.

“He started photographing when he was six, and was still photographing when he was 90, and he lived through the whole century,” says Scherman. “He did a book called Diary of a Century, and he was there for everything. And it turns out I was sort of like that. What’s happened is the pictures I did 50 years ago have gathered a lot of gravitas. So, now all these pictures that were for me just doing a job have turned into an icon of an era, which I think is kind of neat.”