“Much of my work reckons with home and elsewhere as two foundational stories we tell to explain who and where we are,” says the visual artist and architect known as Bz (pronounced “bees”). “To me these terms are two sides of the same coin because they are both principles of inclusion and exclusion: what is familiar or belongs is considered ‘home,’ while that which does not belong, which is excluded, is considered ‘elsewhere.’ ”

As a 2022 Twenty Summers fellow, Bz will be presenting a workshop titled “Home and Elsewhere: Co-Creating an Atlas” at the Hawthorne Barn in Provincetown on Saturday, May 14. An atlas “allows us to think about home and elsewhere on every scale,” they say, “from the body to the infrastructure to planetary space and across time.” Making one is a chance to examine how experiences are layered on top of each other to create a place.

Workshop participants will be invited to bring along their own “cartographic tools,” which may be drawings, photographs, texts, found objects, and roadmaps, or personal stories, celebrations, and intimacies. They’ll be used to explore shared meanings of home and elsewhere, with a particular focus on Provincetown, its history and surroundings.

“I’ve been preparing for my time in Provincetown by going through historical maps,” says Bz, who lives and works in Los Angeles. “What I would like to do with folks is think through this entanglement of physical and cultural construction” spanning colonialism, the blossoming of the town as a gathering place for artists, and more recently the LGBTQ communities finding refuge and venues for celebration here.

Identifying as a queer, nonbinary, trans, Chinese-diasporic U.S. American, Bz has been confronted with questions of home and elsewhere — of belonging and of being excluded — throughout life. “My parents come from Shandong province and Anhui province, where I still have intergenerational family connections,” they say. “I have always known a sense of cultural belonging, while still being read as alien and other by each culture that I belong to.”

Bz learned at a young age that when they drew, they would be understood by both Mandarin and English speakers. Creating art became their “third, visual language,” and a way to communicate their values.

While studying visual arts at Brown University, Bz went from making drawings and paintings to creating installations. Their urge was toward more expansive expression, “making art bigger,” which happened to coincide with “making home in more places.” Working as a furniture designer and fabricator for a design-build firm in Philadelphia led the way to an interest in architecture, which Bz pursued at the University of California, Berkeley.

Architecture, Bz points out, has often been complicit in oppression. Drawing a boundary or erecting a wall changes people’s ability to access a space. The question, Bz says, is how to use the skills of architecture with care. They are part of the Design as Protest Collective, which aims to reverse injustices inflicted by design, architecture, and urban planning.

Now, Bz considers most of their work, whether painting, design, or architecture, to be portraiture.

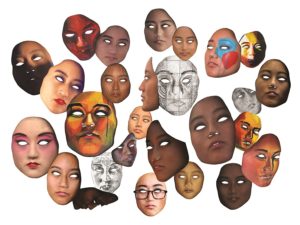

One current body of work draws from Mandarin and English phrases using the word face. “As an adult child of immigrants, I grew up bilingually with the phrases ‘lose face,’ ‘give face,’ and ‘save face’ as both expressions of the Eastern culture my family came from and also cues or survival tactics around assimilation, compliance, and safety,” Bz says. Now, the word is a reminder of the power of agency over one’s own body.

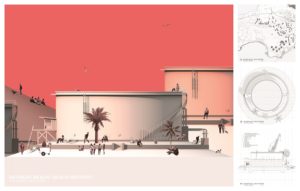

Bz’s Elsewhere architectural drawings are “portraits of places.” One of them, “refinery beach / beach refinery,” juxtaposes the way the Chevron Corp. describes its refinery in the Bay Area town of Richmond as “a vital part of the local community” with its reputation for pollution and toxic spills.

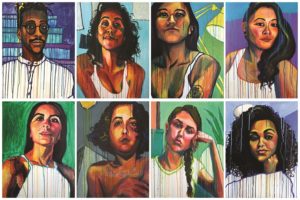

Sometimes Forever is another series that captures where we perhaps most essentially consider ourselves at home: with our loved ones. It is a seemingly everyday collection of friends’ “selfie” photographs that together create a portrait of their collective grief. It is dedicated Nick Gomez-Hall, a friend they lost in the Ghost Ship warehouse fire in Oakland in 2016.

For Bz, the series is a meditation on the acceptance of futility. For example, the futility of portraiture — the loved ones we paint will still one day be lost, they say. But, Bz believes, it’s that acceptance that opens the way “to commemoration of our tender, ordinary, everyday moments with each other.”