If you’ve walked down Commercial Street in Provincetown, you’ve likely met the tourists standing outside the public library. Immortalized in bronze by sculptor Chaim Gross, the couple — a large-chested woman towering over a pot-bellied man — have been standing there for years. They gaze disaffectedly across the street, their forms a play of alternating heights and protruding masses.

The sculpture, titled Tourists, is owned by the town of Provincetown and managed by the Provincetown Art Commission. The commission is responsible for maintaining the town’s collection of approximately 300 donated works, which are displayed in public buildings, including many in the Provincetown library.

Within the library, “the art commission determines what is hung and where it is hung,” says Stephen Borkowski, a member of both the art commission and the library’s board of trustees. “We try to pick pieces that are going to enhance the visitor experience and tell something about the history of Provincetown. It’s not only decorative — it’s instructive.”

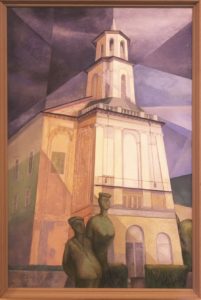

Mary Spencer Nay’s painting Homage to Heritage Museum and Chaim Gross hangs above the library’s scanner. It reads like a narrative: Nay places the viewer on the street at a low vantage point. Gross’s sculpture occupies the foreground, the figures in shadow with their backs to the building, which arises as a beacon of light. The façade glows against a dark blue sky divided into geometric shapes.

Originally a Methodist church, the structure served as a museum of local history before becoming the town’s library. Nay’s painting nods to the building’s history as a place of inspiration and culture, with Gross’s figures as stand-ins for ignorant indifference.

Nay places herself in conversation with Gross. Both artists studied in Provincetown and returned throughout their lifetimes, Gross buying a home on Franklin Street in 1942 and Nay visiting in the summers beginning in 1937. After her retirement from the University of Louisville, Nay moved to Provincetown full-time. She died here in 1993.

In addition to reflecting cross-pollination among creative peers, the library’s collection reveals connections across generations of Provincetown artists. The married couple Oliver Chaffe and Ada Gilmore, active in the first half of the 20th century, represent a generation older than Nay. Yet the influence of Chaffe and Gilmore’s cubist style can be seen in Nay’s Homage.

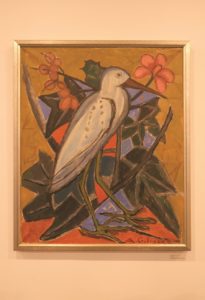

On the first floor, Gilmore’s painting The Heron hangs above a cluster of computers, the white bird dominating the canvas with a group of plants rendered with sharp shapes. The space within the painting is compressed, reminiscent of Egyptian art. Chaffe continues this mode in two large paintings in the children’s section. In March Hare, the animal’s face references African masks, a favorite obsession of early modernists, its body covered in abstract shapes. The adjacent painting, Untitled (Bird and Dog), depicts an abstracted scene of what appears to be a wizard astride a bird-like creature, a dog stretched out at the bottom of the composition. These playful paintings are hung above a colorful play area.

Fantastically, a half-model schooner, the Rose Dorothea, stretches 66 feet across the center of the children’s section on the second floor. Beginning in 1977, Francis “Flyer” Santos led a team of volunteers to create “this grand tribute to the fishermen of Provincetown and to New England’s ship-building tradition.” It was completed and installed in 1988 for the Heritage Museum. “We get a lot of tourism for that,” says Nan Cinnater, the reference librarian.

One of the paintings near the schooner is a portrait of Santos by Salvatore Del Deo, an artist who, in his 90s, still lives and works in Provincetown. It’s a great character study. Flyer sits stiffly, his hands balled into fists. Del Deo squeezes Flyer’s burly torso into the painting’s frame, his head perched atop the composition. Santos looks out at the viewer, guarded. His chin is sharply defined and shadowed against the soft, lighter flesh of his neck. This, along with the delicate colors in his fists, tempers the masculine image.

Del Deo’s portrait is one of several of Provincetown personages in the library. In S. Edmund Oppenheim’s soft-edged portrait of Harry Kemp, hanging on the mezzanine level, “the poet of the dunes” literally has his head in the clouds. Kemp’s windblown white hair and blue-gray eyes echo the sky above him. A seagull flies above his head, symbolizing the freedom associated with this eccentric visionary.

Henry Hensche’s Portrait of Margaret Mayo Expecting Motherhood, in the magazine section, represents another side of the Provincetown community. Mayo’s blue dress and serene face recall paintings of the Virgin Mary. Mayo, who lived to 100, married into a family of seafarers and was a Provincetown fixture, working at several local businesses before running the East Harbour cottage colony in North Truro.

Another Hensche painting adorns a hallway. A bit out of the way, this painting of a summer garden shows how Hensche finds color in shadow and dramatizes light. Influenced by Impressionism, Hensche first came to Provincetown to study with Charles Hawthorne before becoming an influential teacher in his own right, counting Del Deo among his many students.

The Provincetown library has become an art destination in its own right. Maybe not for the likes of Gross’s uninterested tourists, but for those curious about Provincetown’s past, says Borkowski, “It gives them a sense of the town’s history as an art colony.”