To those unfamiliar with cryptocurrency and NFTs, the term “non-fungible” sounds more like a type of mushroom than an economic term. But the buzz around non-fungible tokens, or NFTs, has increased in the last few years. In 2021, the auction house Christie’s sold its first NFT for $69 million.

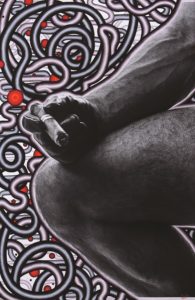

Almost exactly a year ago, Greg Salvatori introduced fellow Provincetown artist Gaston Lacombe to The Queenly NFT, an “ethical cryptogallery for queer creators,” according to its website. Lacombe and Salvatori elected to donate 5 percent of their NFT sales proceeds to Summer of Sass, a program that brings LGBTQ youth from other parts of the U.S. to Provincetown for the summer.

The Queenly NFT website defines a non-fungible token as “a collectible record of a unique digital item.” If something is “fungible,” you can exchange it for an identical commodity. NFTs function as certificates of ownership embedded in the code of a digital image, video, or graphics interchange format (GIF) stored on the blockchain, which is a digital record of all cryptocurrency transactions.

Lacombe and Salvatori aren’t the only Outer Cape artists to hop on the bandwagon. Kai Potter of Wellfleet makes a daily sketch that he posts on Instagram and OpenSea, a digital marketplace for creating, selling, and trading NFTs. But his Daily Draw series has yet to garner any trader traffic.

Critics of NFTs question their viability and their carbon footprint. The New York Times reported that creating an NFT uses as much carbon as driving a gasoline-powered car 500 miles.

“I went into this thinking I had nothing to lose,” says Lacombe, who was a photojournalist before becoming an artist. He says he’d often find his uncredited work reproduced in other newspapers. This made the idea of encoded ownership attractive to him. Artists who make NFTs can code a royalty rate into the blockchain, which guarantees that they make a profit every time the NFT is resold.

At The Queenly NFT’s outset, there was “a lot of hype, a lot of hope,” Lacombe says. “Then, nothing happened.”

Though Lacombe advertised his NFTs through social media and his newsletter, no one bought any of the eight he posted on OpenSea. He thinks this might be because most of those viewing or buying his work live in or around Provincetown. The smaller scope might mean it’s less likely that a buyer who’s into crypto comes along.

Salvatori, on the other hand, says he’s made about $10,000 investing in cryptocurrency, and he says he sold a few NFTs before joining The Queenly NFT. Having previously lived and worked in Milan, London, Florence, and Paris, he has a following in Europe and wider array of customers who use cryptocurrency.

Salvatori started accepting crypto payments for physical prints of his photographs about three years ago. He says he once sold a print to a Dutch customer using the currency Dogecoin. At the time, the exchange rate between Dogecoin and American dollars was low. Soon enough, though, the value of Dogecoin rose, and Salvatori ended up making $3,000 from that print, which was originally priced at $2,400.

Salvatori confesses he’s attracted to the “game” of timing investments based on fluctuating value. He thinks Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies are “kind of caricatures” of the stock market. Though there’s opportunity for risk and reward, he doesn’t see NFTs “as an investment in terms of making money for an artist.” What he’s made from selling NFTs has not changed his life, he says.

“I see it more as a cultural investment,” he continues. “This is yet another way to anchor your work in a space. And the space is on hundreds of thousands of different servers around the world.” Photos fade, burn, or get lost, but blockchain data survives as long as there’s electricity to provide the processing power required to store it. Plus, his work is visible to anyone with internet access.

Some aren’t as excited at the prospect of an online legacy. “As an artist who works digitally,” Shann Treadwell, who makes collages from photographs of drag queens and other queer icons, says he understood the appeal. But NFTs “sounded like a ridiculous way to spend your money.”

Treadwell says he’s less concerned about the environmental effects of NFTs than he is skeptical of their inherent value: “What’s the difference between what the person who owns that ape sees and what I see on my computer?” he asks, referring to the Bored Ape Yacht Club, a collection of 10,000 unique NFTs featuring the same simian character wearing different accessories. “We’re both looking at it through a screen.”

Treadwell and Lacombe both feel that owning an NFT versus looking at it on the internet do little to change someone’s experience of art. “In terms of the business I have here, I’d rather invest time into making physical art that I can sell,” says Lacombe. “My priority is making real money.”