Beginning in the Cape’s dunes, Ben Shattuck’s Six Walks is a meditation on nature in Henry David Thoreau’s footsteps. Desperate to escape recurring nightmares, Shattuck turns Thoreau’s Cape Cod into a treatment regimen. He packs his journal, just as Thoreau did, and dresses for the beach, hoping to find peace in the act of walking.

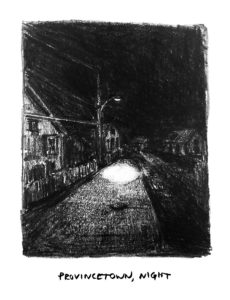

The Cape walk inspired by Thoreau — starting near Eastham’s Nauset Light and ending in Provincetown — is only the first of the book’s journeys through nature, which stretch as far as Maine. Yet it becomes a touchstone in Six Walks, ultimately calling Shattuck back to Provincetown’s coastline years later to finish the book.

A 2019 Pushcart Prize winner, Shattuck serves as director of the Cuttyhunk Island Writers’ Residency and is curator of Dedee Shattuck Gallery in Westport. Six Walks often finds Shattuck reflecting on the landscape of his native Southeastern Massachusetts. (He now runs Davoll’s General Store in the town of Dartmouth with his brother, Will.)

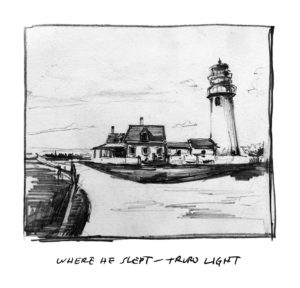

Shattuck is also a painter. The book includes his journal illustrations as accompaniment to his written reflections. Though they are pleasing additions, the prose doesn’t need them — Shattuck’s descriptions match Thoreau in their beauty and sincerity. Setting out along the Cape, he writes, “High tides feel favorable, as does anything overfull — waterfall, blooming peony, snowbent tree limb, spilt milkweed seeds. The high tide felt purposeful, then. The ocean leaning inland, urging.”

Six Walks brings to life the sides of Thoreau often obscured by the tracts we all decipher in high school. “Thoreau’s nature is accessible,” Shattuck says, “a single daffodil that’s pushing up through the newly thawed soil.” As a result, “the beauty he finds in nature is human-sized, not state-sized. And so, in a place like Cape Cod, you can still see and feel and hear all the things that he was accessing in many ways, even though the landscape is different now. If you shut off your cell phone and just listen and watch, there is the same source material in front of you.”

Though separated by time and space, Shattuck’s walks are connected by his belief that the landscape possesses a transformative power. “The landscape, I wholly believe, makes you feel things,” Shattuck says. “There are real emotions that pass through you that are connected to our most prehistoric selves.”

Early in his Cape walk, Shattuck realizes that the coast’s monotonous landscape — sea on one side and “bayberry, huckleberry, and the odd scrub pine” on the other — is failing to provide enough distraction from his own internal “conveyor belt of sadness.” Instead, he finds himself “clinging” to the strangers he meets along the way. There’s the birder, “thrashing at him with questions about the migratory routes of loons”; the eccentric billionaire in Provincetown; the artist couple that remain his friends to this day.

At the end of one of Shattuck’s walks, he finds himself gazing at the Wellfleet oysterman’s house on Williams Pond, where Thoreau spent a night. The sight leaves Shattuck a little deflated, but when a couple welcomes him into their home, the experience brings him closer to the sublime.

“Without a plan, with only an impulse to walk, I’d finished the day here: in the home of kind strangers who’d served fried scallops for dinner and told stories about winter ice fishing on the pond just out their door,” he writes in Six Walks. “I had a clear feeling that I was supposed to end up here.”

Whereas Thoreau seemed to find evidence of a higher power in the vistas he captured, Shattuck finds it in the people he meets while seeking those same views. “I think what was so magical about my Cape walk, and why I still hold it as the most special in a way of my walks, is because it was like I opened a door that I didn’t know existed in a house I’d lived in for a long time,” says Shattuck. “There’s no way to plan that — no way to plan to meet the people that I did and have them welcome me. There’s no way to plan how beautiful it was to row across these lily pads in the early evening towards the oysterman’s house. Something about that — the fact that it was unplanned — felt like fate and could be called sublime.”

But Shattuck’s prose is also haunted by the specter of perilousness. Climate change hovers at the edge of the sand dunes, reminding him, and the reader, how pollinator life cycles have become vulnerable, and the land itself has shifted since Thoreau’s time. Shattuck acknowledges that the freedom he feels in the woods is a privilege that not everyone enjoys.

The book doesn’t offer a clean answer to the problems that skirt its edges, or even the personal troubles that inspired Shattuck’s journey. Instead, it gives readers a model for how, standing together in admiration of a crest of sand or a loon’s call, we can find connection that is — just maybe — a little transcendent.