As an elementary-school student in Virginia, Elizabeth Flood found a Civil War bullet while digging in the sand at recess. “It was on my radar at a very early age that there are many layers of history happening anywhere you stand,” says Flood, a visual arts fellow at the Fine Arts Work Center this winter. “That’s still in my work.”

Flood grew up outside Washington D.C., where things “were constantly changing” and “lots of people were moving in and out for government and military jobs.” She witnessed the rapid development of the area and remembers the first strip mall being built. She became keenly aware of “things built on top of other things.”

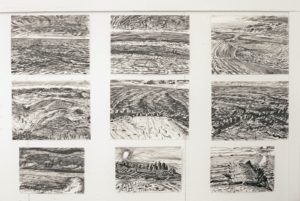

In Provincetown Flood is contending with different changes — namely, the tides, wind, and weather — as she works on plein-air ink drawings and paintings of the dunes.

She began her stay here creating drawings of a shipwreck visible only at low tide. “I loved the feeling of trying to keep up with the tides,” she says. “I like the structure that gave my work.” The resulting images are quick and gestural — racing lines describe sand and water; sharp, jabbing marks describe the topography and ship’s carcass. More than anything, Flood is drawing weather.

In her 11-foot painting Race Point, Flood combines five panels, each a different perspective of the same beachscape. In one panel, the sky is stained with the soft colors of coming twilight. In another, ominous clouds hang over a turbulent ocean. She communicates a holistic experience of the landscape, forgoing a single perspective for changing weather and shifting vantage points.

Flood began creating multi-panel paintings as an M.F.A. student at Boston University. She was fascinated by a former quarry in Quincy that, long abandoned as a source of industry, became a dangerous swimming hole before being filled with land from the Big Dig and transformed into a park. “Somehow the single canvas of the landscape was starting to let me down,” says Flood. “I wanted to make something that could hold all these layers and feel closer to what it is to move through the space.”

As Flood worked in the space, she was struck by “the public but very private expression of graffiti” and “all these personal messages of grief, loss, joy, and humor,” she says. “The anonymity of it was so beautiful. It was almost like prayer.” This sentiment found its way into her work. “When I was in graduate school, my mother died, and I felt as if, being in this place that held a lot of grief, I could just let it all out into the paintings,” Flood says.

In her show “Battlegrounds” at Real Art Ways in Hartford, Conn., Flood layers the personal with the political. She began painting Gettysburg on July 4, 2020 after watching busloads of armed alt-right militias visiting the Civil War site. “It was disturbing to see history repeating itself in a place that had already seen so much death and hate and violence,” she says. Compelled to “keep coming back” in the time leading up to the 2020 presidential election, she felt “the charge and turbulence of our country matched the charge and turbulence of that land.”

Flood describes the resulting artwork as “emotional, primal scream painting.” She scratches into the thick paint, which she mixes with grass ripped from the ground. The land is rendered in putrid greens, acidic yellows, and scorched browns.

And then there are sunsets on Cape Cod. In an unfinished painting on Flood’s studio wall, soft pastel colors describe a hollow in the dunes, the sand reflecting the purple sky. “The sky is the lamp that touches everything,” Flood says. Yet, a heaviness also permeates the work. She mixes pumice powder into the oil paint, creating a cement-like texture that she “carves” with a dry brush.

A few hours after speaking in her studio, we meet up in the dunes. She lugs the unfinished painting and her palette to a crest with sweeping views of the Province Lands. The forecast calls for rain and snow, but Flood isn’t deterred. Sandbags anchor her easel; clamps hold down the canvas. As a Catholic, she admits there’s something “penitential” about the way she paints only outside, in all weather. She also describes “a kind of ritualistic quality” to her practice — “the pilgrimage to the same spot, the carrying of all the gear to get there.”

By the end of the day, Flood has painted through wet snow and swirling winds, reorienting her easel so the rear of the canvas “took the brunt of the snow.” The oil paint has turned “resistant and slushy” from the elements. But, miraculously, she finishes the painting — the purple and pink landscape viewed in her studio is transformed into one that is gray and somber, dotted with prickly shrubs.

Some might prefer the underpainting with its ease and openness. But Flood wishes to convey something hardier and more experiential — a grace and beauty earned through struggle. “There’s something vital in these paintings, in the way I’m painting and fighting with the place,” she says. “It still feels very fraught and unsettled. There’s still a lot about loss and grief, life and death.”

After the Flood

The event: A show of works by Elizabeth Flood

The time: By appointment; Friday, March 18 through Tuesday, March 22; reception Friday, March 18, 5 to 7 p.m.

The place: Hudson D. Walker Gallery, Fine Arts Work Center, 24 Pearl St., Provincetown

The cost: Free