Poets build poems within the shells of earlier work, caterpillar to moth. We learn to write by reading and echoing until something clicks that feels genuine and new. I love having students “Mad Lib” a poem that they admire, replacing every bit of it — noun for noun, verb for verb — until it is transformed by their own experience and vision.

I asked benthic ecologist Agnes Mittermayr, who works at the Center for Coastal Studies, to do just this. Agnes reads poetry, but she has never tried to write it. Born in Austria and a Cape Cod resident since 2015, Agnes is my walking/reading/naturalist friend. We often swap books. Two of my favorite things about Agnes: she loves marine worms, and Kurt Vonnegut is the writer she seeks when she needs cheering up.

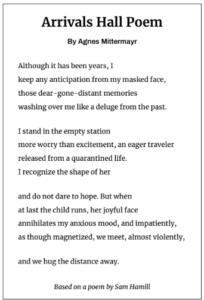

Agnes chose Sam Hamill’s “Black Marsh Eclogue” to trace (you can find the original at poets.org) because she liked the rhythm — a wonderful reason to choose a poem! At first, she thought she might write something nature-related. Then she considered inventing a parallel story. In the end, she decided to write about her own experience.

The pandemic has kept Agnes away from her Austrian family, including her young niece. This past December, she finally got to visit home. Before she saw her niece, Agnes was full of Vorfreude, a German word meaning “pre-happiness.” It is a word slightly different from anticipation, as it signifies pure and absolute joy. This is one of many wonderful German words Agnes has taught me. Others: Waldeinsamkeit, the feeling of being alone in the woods in the best way possible; and Mutterseelenalleine, translated roughly as “mother-soul-alone,” the feeling of being utterly and devastatingly alone in the world.

Once Agnes began writing, the process went relatively quickly. For her, the intimidating part was the vocabulary: German is Agnes’s first language, and one could say that science is her second.

Once Agnes began writing, the process went relatively quickly. For her, the intimidating part was the vocabulary: German is Agnes’s first language, and one could say that science is her second.

After her first draft, we met on the East End flats to walk her dog and chat. It was a perfect evening to talk poems: diffused light and glassy water, the calm before an epic storm. Agnes had a few words she was frustrated with, a few places where the sense seemed right, but sound and rhythm were wrong. We played with options, discussing why it was important to include certain ideas and gestures.

When I asked Agnes how writing had felt, she said what every poetry teacher hopes for: “I didn’t know where I was going.” But, she said, the experience was liberating — like putting the whole spectrum of emotions on paper.

Picturing Agnes arriving in Austria after years of separation, anticipating the reunion with her niece, I’ll gladly admit that I choked up when I read her poem. “Will you share this with your family?” I asked. “I don’t think they have the English,” she responded. I’m not so sure. I think the love would shine through without any translation.