Sitting in her studio in Provincetown, Ellen Akimoto says she has “a weird feeling of being at home and definitely not at home.” Originally from California, Akimoto arrived as a fellow at the Fine Arts Work Center after having lived and worked in Leipzig, Germany for the past eight years.

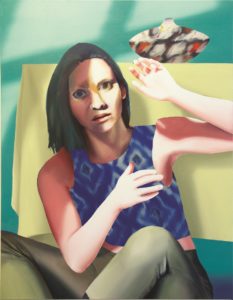

Her work, too, seems to occupy a space between the known and the unexpected. Akimoto paints uncanny worlds in which objects and bodies hover in half-believable situations.

Akimoto grounds herself by working on life-size figure paintings and smaller still lifes. Her cube-like space is strewn with stencils, Photoshop printouts, and piles of discarded tape, which she uses to achieve hard, clear edges. Pink is a dominant color in two of the large works-in-progress that sit in the studio as she prepares for her solo show at the work center’s Hudson D. Walker Gallery, running Wednesday, Feb. 16 through Tuesday, Feb. 22.

As a student at Leipzig’s Academy of Fine Art, Akimoto knew what she wanted from color. The East German institution, with roots in Soviet-era Social Realism, is well known for fostering figurative painting. Many graduates of the academy grapple to some degree with this tradition, including most notably Neo Rauch. Akimoto noticed people coming out of the Social Realist movement skewing toward “dark, dreary” colors.

“I knew I didn’t want that,” she says. “I wanted something brighter.” Soon she gained a reputation for working with color in a way that her peers labeled uniquely Californian.

Akimoto’s journey from California to Germany began as an undergraduate at California State University, Chico. She heard about an exchange program in Mainz, Germany through a boyfriend. Abandoning a plan to study in Italy, she spent a year in Mainz and “fell in love with Germany and the German art system.” She decided to return to Germany for graduate studies.

“I kept hearing about Leipzig while in Mainz,” says Akimoto. “It was well known for figurative painting. I had never gone to a school where figurative painting was the thing.” Unlike American art schools, German schools work according to the master-apprentice model. With reviews only once a month, “we were forced to be self-motivated,” Akimoto says.

Eventually, Akimoto built a life for herself in Leipzig, making connections and gaining fluency in German. After graduation, it made sense to stay. “I had my whole network of people there,” she says. “The cost of living was so low, and there were lots of opportunities for artists. I couldn’t see any other way to make it work.” Plus, Akimoto was beginning to feel at home, enjoying a work-life balance “where people take care of themselves” and the way German people fell easily into earnest conversation.

“We exist in these contexts and become used to them,” Akimoto says. “I’m interested in the moment where this cracks and we see other possibilities.” As Akimoto’s German experience expanded her horizons, her paintings also began to explore different perspectives. “My goal is to make images that do not offer a consistent, unified world, but rather one that is complicated by contradictions and allusions to other possibilities,” she writes in the wall text for the group exhibition now on view at the Provincetown Art Association and Museum.

This sense of contradiction appears stylistically on the surface of the paintings. In Fish in a Cup, a small still life at PAAM, Akimoto paints the tabletop and background with a severe flatness, whereas the surface of the cup mimics the tactility of glazed ceramic. In the cup, she convincingly renders the hazy image of a goldfish submerged in water. The overall effect is one of collage, where pieces of the painting sit in uneasy relation to each other, each speaking their own language yet somehow cohering.

One of the works-in-progress in Akimoto’s studio is similarly off-kilter, though more ambitious in scale. “I came up with the concept in the paint, in full scale,” she says. “I don’t usually do that.” But she soon found herself back to the drawing board — although in this case, the drawing board was Blender and Photoshop. In Blender, she digitally created the room from her painting, controlling the lighting and adding objects, and using the resulting image as a reference. In the painting, the Provincetown landscape appears through a window, providing what Akimoto describes as “a luminous, sublime space” countering the dark interior and artificially lit foreground.

In concert with her heterogeneous stylistic moves and disorienting spatial shifts, Akimoto represents figures in a state of awkward unease. The people in her paintings, most often women bearing a resemblance to herself, exist in “moments of flux” where “something’s about to happen,” says Akimoto. A woman appears to be falling in the large work-in-progress. In the other paintings, the women appear mid-gesture, their eyes transfixed as if under the sway of a paralyzing, mystical experience.

“We live in worlds that we make and uphold but we’re also beholden to them,” Akimoto says. These constructed worlds begin to fall apart in her work, leaving the figures — and the paintings — awash in instability.

“I love moments where I’m mistaken,” she continues. Whereas another artist might find these a cause for despair, in Akimoto’s hands they become a cause for invention and celebration, a place where bright color and raking light temper an unsettling reality.

Uncanny Valley

The event: A show of works by Ellen Akimoto

The time: By appointment, through Tuesday, Feb. 22

The place: Hudson D. Walker Gallery, Fine Arts Work Center, 24 Pearl St., Provincetown

The cost: Free