Congressman Jamie Raskin’s new memoir is about surviving the end of his world, and a warning about preventing the end of ours.

On Dec. 31, 2020, his brilliant and empathetic son, Tommy, died by suicide at age 25 after a long struggle with depression. He had just finished his third semester at Harvard Law School and was living at home with the family in Takoma Park, Md. His suicide note read in part: “My illness won today. Look after each other, the animals, and the global poor for me. All my love, Tommy.”

“Rocking back and forth sobbing,” Raskin writes, “all I could say was ‘My boy, my dear Tommy. My boy, my dear boy. I have lost my boy. My life is over. My life is over. I have lost my Tommy, I have lost my son. My life is over. My boy, my dear boy.’ ”

Less than a week later, Raskin and members of his family were trapped inside the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6. His daughter and son-in-law hid from the mob inside House Majority Leader Steny Hoyer’s office. Raskin and other members of Congress narrowly avoided the insurrectionists as they were scuttled from room to room. Raskin recalls watching Democratic members of Congress crawl to the Republican side of the House floor because they guessed a mass shooter would be less likely to fire at that side of the room.

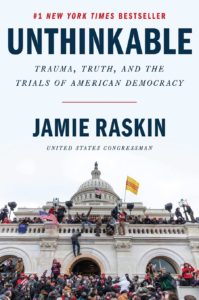

While Tommy’s suicide and the insurrection were “cosmically distinct and independent events,” Raskin writes, “I will probably spend the rest of my life trying to disentangle and understand them to restore coherence to the world they ravaged.” In Unthinkable, published this month by Harper Collins, Raskin sifts through grief and guilt, recounting the first 50 days of 2021, when he led the second impeachment trial of former President Donald Trump. Amidst “two impossible traumas,” Raskin writes, that work became a “salvation and sustenance.”

In the moment, Raskin believed Jan. 6 had created a powerful enough shock to rouse enough GOP senators, whom he likens to “religious cultists asleep in the back of a repainted school bus,” into convicting Trump. Indeed, while being shown footage of the violence for the very first time, Sen. Rand Paul “seemed not to be watching at all,” Raskin writes. Mitch McConnell, on the other hand, was “tearing up,” and “could lose it.” Trump was ultimately acquitted by a vote of 57 to 43, 10 votes short of the two-thirds majority needed to convict, with McConnell voting to acquit.

A year after Jan. 6, Raskin cautions that the GOP’s decision to choose its “raw power” over the Constitution has undermined our collective memory of the insurrection and threatened democracy at large. Raskin compares the Big Lie to the Covid deniers and propagators of the Lost Cause myth. “The perpetrators of these Big Lies know that human memory is a fragile instrument and that what we ‘remember’ of an event can easily be influenced by what others tell us to believe about it or by the constant repetition of lies about it,” he writes.

With Trump still firmly atop the GOP and trading Big Lie loyalty for endorsements, Raskin warns that the next presidential election could be overturned even without another violent insurrection. “Assume (not hard to do) that Trump again cries fraud and asserts that Biden electors should be ‘returned’ to their state legislatures and the contest thrown into a contingent House election,” Raskin writes. “My fear is that GOP leaders — having been totally whipped by Trump and the violent insurrectionists, and having effectively purged themselves of dissenters like Liz Cheney, John Katko, Richard Burr, and Bill Cassidy — would snap to attention and grant Trump’s wishes, rejecting enough Biden electors to activate a contingent election and get Trump elected ‘immediately’ in the House.

“The permutations and possibilities of a full blown presidential election breakdown are infinite in the haunted house of the electoral college,” he writes.

This sense of doom is nearly absent when Raskin writes about Tommy. While Raskin’s experience of losing his son will always be associated with “misery and suffering,” he writes, “When I see Tommy Raskin, I see him laughing uproariously, smiling at the center of attention, darting around and making everyone laugh, telling jokes and intricate stories, spreading joy and soaking it up.

“Tommy was born to be a provocative public thinker and a humanitarian activist,” Raskin writes. He never got his driver’s license because he didn’t want to be responsible for causing harm. From college on, he donated the “vast majority” of the money he made to a group called the Effective Altruists. He became a passionate vegan because “he was convinced that by numbing ourselves to the agony and suffering of animals, we conditioned ourselves to accept the brutalization of human beings.”

An excerpt from one of Tommy’s poems about this topic, entitled “Where War Begins,” reads: “To justify killing, we call victims a pest, for their devious manner and intolerable zest, for seduction, destruction, and bold criminality. Whose scheming demeanor bespeaks animality.”

As Raskin writes of his son, “There would be no middle path for Tommy.”