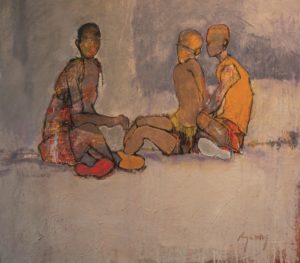

For Laurence Young, each painting is a journey into the unknown. “What I put down first on the canvas has nothing to do with what I’m going to do later,” he says. “I have no idea where I’m going when I start.”

Young begins his canvases with a ground, which can be anything, even leftover paint on his palette from his last painting. It’s just something to cover the canvas and to prime his emotional response to the materials that will fuel his process.

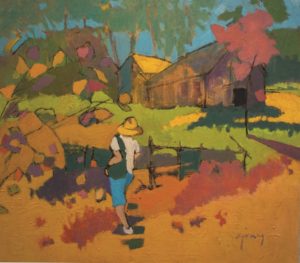

Then comes the line, in charcoal or oil pastel, arguably the most important element of his artwork, though Young insists he’s a colorist. Young doesn’t paint out the line except for rare occasions. Finally, colors of close value are applied side by side. This technique, while similar to how impressionists apply complementary colors next to one other, results in more subtlety. The colors are applied and scraped off, applied and scraped off, until a painting is revealed.

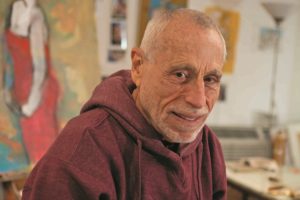

While Young’s paintings start from a place of uncertainty, he has always been confident in his desire to be a full-time artist. He was born in Newton Centre.

“It was the ’50s and very rural, not built up like it is today, and the only caution was to look both ways when crossing the street,” he says. As a kid, he cherished trips to Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts with his mother and art classes. “I generally made a mess but enjoyed it,” he says. “It’s pretty much what I still do today: make a mess of the canvas.” In high school, he hung out in the art room and theater department.

After high school, it was off to the University of Hartford for a degree in art education, then a three-year stint as an elementary school art teacher. “I loved teaching, but it was a stepping stone,” he says. He was accepted to the Rhode Island School of Design as a printmaker. “I love the graphic nature of printmaking,” he says. “I like the process and the simplification, playing with illusion and space on a two-dimensional surface. To this day, Joseph Albers is my go-to man when I’m stuck, and much of his work is screen printing. Putting all that together made sense at the time.”

Upon graduation, Young landed in New York and started his own company, Young Ideas, a design firm specializing in women’s sports apparel that also catered to such clients as Care Bears and American Greetings. He still printed when he could, but he says the work was inconsistent.

Then the AIDS epidemic hit. “I was completely blown away,” Young says. “I sold my company and that became my seed money to paint full time. Everyone said I was crazy. With the onset of AIDS, I reassessed my life and felt that it was time to make a change.”

Young moved back to Boston and commuted to Provincetown. “I bought a very tiny place to crash,” he says. “Eventually, I ended up moving here.” He’s now represented locally by Ray Wiggs Gallery.

Though experienced in the commercial world, Young arrived in Provincetown without real fine arts chops. “My background was mostly graphics and printmaking,” he says. “I didn’t have a lot of drawing skills, and what little painting I did was acrylic, so I came into oil painting as a self-taught artist. I started working at PAAM’s open anatomy drawing and became a fairly accomplished person who could draw. It was a struggle, but the drawing helped the painting.”

Young notes the unspoken hierarchy in the art world. “Oil painting is at the top and somewhere at the bottom are watercolors,” he says. “I kept graphics and drawing and painting separate for years. It was a purist attitude.” But when Young took a workshop with Provincetown painter Cynthia Packard, the trajectory of his art changed.

“Here was everything I was looking for,” he says. “She combined line and composition and color. Suddenly, I’m seeing this person who is taking these elements that I’m good at and putting them together and I’m asking, ‘Why not?’ ” Packard’s influence can be clearly seen in Young’s work, along with the Austrian painter Egon Schiele and the printmaker Käthe Kollwitz, whom he considers inspirations.

Unfettered by the academy, Young developed a style that is uniquely his. “The real challenge is to decide what to play with on the canvas,” he says. “I’m not painting what or how other people are painting. I get bored easily and what keeps my work consistent is how I approach it. I paint my truth.”