Nineteen writing and visual arts fellows arrived last month at the Fine Arts Work Center for seven-month residencies in Provincetown. One more fellow, Ellen Akimoto, is in Germany dealing with visa issues but expected soon. The fellows will be here through April, with exhibitions and readings of their work beginning in February.

Akimoto makes figurative paintings that use skewed perspectives to create tension for the viewer. “I see the uncanny as this moment when we start to see through or around the edges of the world we’re accustomed to, where things you thought were known are suddenly rendered strange and alien,” she says. “I love the German term for uncanny, das Unheimliche, because it presents itself as the opposite of the heimlich, which is a word with the dual meanings of both ‘homey’ and ‘secret’ or ‘hidden.’ ”

Austin Ballard, a second-year fellow, considers himself an “object-maker who has graduated to a sculptor.” He works in textiles and ceramics to create “repetitive and meditative patterns that confuse and misdirect the audience.” Though his work can look 3D-printed, everything is made by hand.

Working mostly in painting and sculpture, Kevin Brisco Jr. is interested in the “slippage” between figure and background. This began with a painting he made in 2016 of a Black middle class living room. “I’m interested in how backgrounds always show the marks of the individuals who inhabit them,” he says.

For a 2016 performance piece, he converted a New Orleans gallery into a club, complete with bouncer and DJ. “As the party gained momentum, the strobe lights turned red and blue, and sirens sounded.” Then, 28 performers opened black umbrellas, representing the number of Black people killed so far that year by police violence. “The audience was left in silence from what was until that point a very good party,” he says.

S. Emsaki works in video, painting, printmaking, performance, and writing to explore “natural resources, such as water and oil, and the way that they shape the fate of a people.” She’s also interested in “things that have no substance, such as shadows.” She’s currently working on a gas pump that will be imitating the dance of the Sufis.

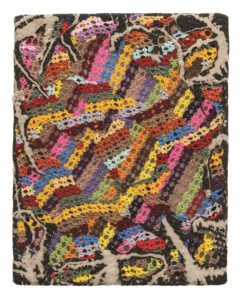

Lately, multimedia artist Nick Fagan has been making afghans, the grandmotherly blankets often found in thrift stores. He is interested in objects “made with love,” ones that express “sincerity.” His other work in textiles, drawing, and sculpture stems from his experience with dyslexia and the “abstraction of language.”

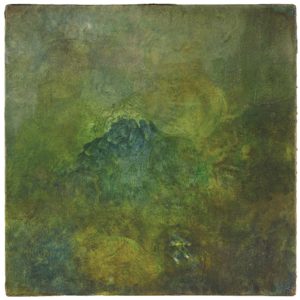

Originally from Virginia, artist Elizabeth Flood paints in the field, to “parse out different layers of experience — historical, emotional, geological.” She has done a series of Civil War battlefields and is working on one of ink drawings of Provincetown. “Being at the site itself is important to me,” she says. “You experience the cold, the heat, the crunch of grass.”

It is far from painter Tom Pappas’s first time in Provincetown. He was here as a FAWC fellow in 1991. A few years later, he started working as tenzo, or head chef, at the Zen Mountain Center in San Jacinto, Calif. “It was a great experience within a wonderful small community, not unlike FAWC in some ways,” he says. “I segued from cooking to fish mongering about 20 years ago, so the Cape was a logical place to paint and work. Getting the second-year fellowship came as a complete surprise to me. I still feel like it’s a dream.

“I see my paintings falling into a tradition that goes back to cave walls,” he continues. “Amongst my many jobs, I worked for years as a museum guard. My work these days is a reckoning of all those hours I spent gazing at every inch of innumerable paintings.”

Georden West considers themself part of a “queer filmmaking tradition where reality meets fantasy.” West is currently in post-production for their first feature film, Playland, and is working on a “leather ballet about dykes on bikes.” West is interested in archival work revealing lost subcultures and marginalized communities.

“I didn’t start writing fiction until I was 25,” says Shastri Akella. He quit his job at Google to join a street theater troupe that traveled along the Ganges. It was research for his first novel, a love story set in 1990s India between a genderfluid street performer and a Jewish migrant. Akella’s work explores queerness and displacement. Another novel, Sea Elephants, is coming out in 2023.

Writer Molly Anders, from Kentucky, tries to “conceptualize as little as possible.” But, looking back, her work tends to explore themes of “class, sexuality, gender, and capitalism,” she says. The collection of short stories that she is currently working on is united simply by the fact that “they’ve all been written by me.”

Laura Cresté, author of the chapbook You Should Feel Bad, echoes Anders’s sentiment. “I try not to think about themes and see what’s there later,” she says. Her narrative-driven work explores family dynamics, especially between siblings. Having grown up in New Jersey, she is often drawn to suburban imagery.

Just last month, Tracy Fuad published her first book of poetry, about:blank. “I was born around the time the internet was invented,” she says. Her work, sometimes categorized as “glitch poetics,” explores themes of “dissociation, alienation, identification, and disidentification,” she says. She is currently working on a novel, set in Kurdistan, where she lived for several years, blending fact and fiction.

“I write about where I’m from,” says Sterling HolyWhiteMountain, who grew up on the Blackfeet Reservation in Montana. “Before I started, I’d never seen writing about Indian country that felt familiar,” he says. “I try not to over-conceptualize, as ideas sometimes get in the way of trying to unite real people, which is more complicated than politics.” HolyWhiteMountain is an unrecognized citizen of the Blackfeet Nation because of strict blood quantum laws, he says.

A second-year writing fellow, Vedran Husić grew up in Mostar, Bosnia, which is the setting of many of the stories in Basements and Other Museums, published in 2018. He writes mainly about war, immigration, and cultures of masculinity.

“My mother is Catholic and my dad was raised Muslim, so they were a mixed couple,” he says. “They just raised me like I was Bosnian. My father was in a concentration camp for almost a year, but we were lucky. We went to Germany when I was seven and stayed there for five years. Then we came to St. Louis, which has a big Bosnian community. It was almost like getting reacquainted with my Bosnian identity.”

Eduardo Martinez-Leyva grew up on the U.S.-Mexico border. “My poetry is focused on that area and the violence that is often thrown on brown bodies,” he says. He also writes about trauma and queerness.

Born and raised in Turkey, Zeynep Özakat has been living in the U.S. for a few years. She is working on a collection of “Turkish stories for an American audience” as well as a historical novel, set in the 16th-century Ottoman Empire, about the harems of the Topkapi Palace.

H.R. Webster is another second-year writing fellow. “It is fantastic to be back,” she says. “It is still wonderful to have the opportunity for sustained encounters with writers and artists, to bask in the generative jealousy of people working in different mediums, to dig clams and hike in the dunes.”

Three fellows, visual artist Widline Cadet, visual artist Lavaughan Jenkins, and poet Samyak Shertok, could not be reached before press time.