“Listen, we have a long, rich history,” says Stephen Borkowski, sitting in the Provincetown library’s Cape Cod room. “Provincetown saw the founding of American democracy. The origins of American theater. It’s the oldest continuous art colony. It’s a gay resort, but it’s also full of fishermen’s families. It transcends sexuality and gender. This is the history of a community rich in its tolerance and on very fertile creative ground.”

Borkowski, vice chair of the town’s historical commission, was one of the volunteers who set up the Provincetown History Preservation Project. The digital archive (provincetownhistoryproject.com) contains thousands of works of art, photographs, post cards, newspapers, audio files, videos, and other documents. Enough to send anyone down a historical rabbit hole. And then another.

The project was conceived in 2003 by town hall staff and concerned citizens. The Provincetown Heritage Museum, located in what is now the library, had closed its doors to the public in 1999 for budgetary reasons, says Doug Johnstone, who was town clerk from 2003 to 2017.When it was time to relocate artifacts to the attic of the Grace Gouveia Building (now condos), the hope was to place them in the Pilgrim Monument museum. After those negotiations fell through, something innovative needed to be done.

“We started to brainstorm and that was the genesis of the project,” says Johnstone. “The goal was to find a safe place to preserve the artifacts and make them accessible to the public.” Digitization was a way to increase access. “The more people who had access, the more it would keep the history alive,” he says.

Johnstone asked the selectmen for space to put scanners. They were given the second floor of the former library (now PTV and the Visitor Information Center). After an article appeared in the Provincetown Banner, volunteers came forward. They dedicated a few days a week — meticulously scanning documents, putting them through a word processor, picking out keywords, and uploading them to the site.

“I’m a night owl, so I would go at, say, 11 o’clock in the evening and work until say, 2 or 3 a.m.,” says Borkowski. “It was nice — completely quiet, because it was the middle of winter.”

This was “before there was even Facebook,” says Johnstone. The Provincetown History Preservation Project became a model for the Massachusetts-wide Digital Commonwealth Project. “They would come in twice a year and essentially harvest all the data we had into their larger umbrella,” says Borkowski.

“It’s an amazing thing that our contribution in Provincetown went to this greater digital library,” says Debra DeJonker-Berry, a volunteer and former Provincetown and later Eastham library director.

Sometimes, though, objects were so interesting that it was difficult to stay focused on the task at hand. “It was such a treasure trove, it would be difficult to choose one favorite item,” says volunteer David Mayo. Lyn Kratz remembers a $20 bill printed at the Provincetown Bank in the 1920s. “At first, I thought it had to be counterfeit,” she says. Johnstone recalls a glass plate negative of town hall taken before 1886.

Borkowski’s most memorable item was a controversial letter found under the house of a longtime Provincetown family. “You’ll know what to do with this,” he remembers the family telling him. It was an “appeal to all the decent people in the town of Provincetown” from the 1952 select board, “requesting help to stamp out this degrading and soul-destroying influence,” referring to homosexuals.

“It’s so vitriolic,” Borkowski says. “It’s a reminder that Provincetown was not always as tolerant as it is these days. It’s a window into Provincetown in the 1950s, before things began to change.”

Over the last 20 years, collections grew on top of each other. At the heart are Josephine Del Deo’s artifacts from the Heritage Museum. “I refer to her as our Rosetta Stone for the history project,” Johnstone says.

Many are now housed in the library’s Josephine Del Deo Heritage Archives or on the second floor of Firehouse No. 3, next to town hall. Other works on the website are scattered throughout town after key volunteers, like Susan Avellar, started borrowing items to scan. “I grew up in this community,” says Avellar, “so I knew a lot of families who might have retained historical information that would be of interest to the project.”

“If you want this online or if it’s something you want to memorialize, we will take it,” says Johnstone. “That’s because it all reflects the crazy quilt of Provincetown.”

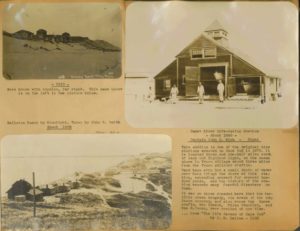

David Dunlap used the database as a major resource in the creation of Building Provincetown. “I could not have done the book without the Provincetown History Preservation Project,” he says. “It just boggles the mind.” Especially useful were scrapbook pages from the collection of Althea Boxell. These include Provincetown Advocate clippings from the 1900s detailing town theater, hidden graveyards from the smallpox epidemic, and the Pamet River life-saving station. Boxell was acknowledged with a dedication in Dunlap’s book for “creating a vivid panorama of the town’s growth.”

While the website states the project is ongoing, it hasn’t been updated since the pandemic. But Borkowski says that will soon change. He and historical commission chair Julia Perry are overseeing a revamping of the project. Anyone interested can volunteer. As they begin setting up their scanners in the library, “we all need a refresher course,” Borkowski says.

Though the archive is impressive, says Borkowski, “it’s by no means complete.”