Salvatore Del Deo first came to Provincetown in 1946 to study painting with Henry Hensche. “When I drove to the Cape the first time, it took six hours from Providence,” he recalls.

Three quarters of a century later, it’s a different town, but Del Deo is still here.

At 93, Del Deo works in his studio several hours a day. He requires help walking to and from the studio. But once inside, he makes his way alone. His mind is as quick as ever, and there’s a brightness in his eye.

Del Deo has been showing at Berta Walker Gallery for 30 years. He is one of the last of the art titans of his generation. He is a living link to Charles Hawthorne, Edwin Dickinson, Hans Hofmann, Ross Moffett, Jack Tworkov, and Franz Kline — his mentors, teachers, and friends, who gave him an artistic foothold here.

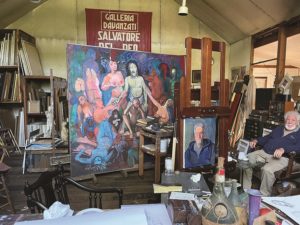

In the heart of town, Del Deo’s studio is magically private — set atop a narrow dirt road surrounded by nature. A path leads to an unassuming green door with flaking paint that opens into an expansive space.

“I built this myself, 30, 40 years ago,” Del Deo says. “A bunch of the wood comes from the beach. I went around town and took the measurements of different studios — Hawthorne’s, Hofmann’s, Dickinson’s, Hensche’s — then designed this.”

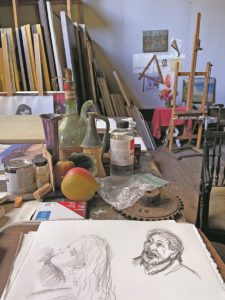

The space is illuminated by tall, north-facing windows. “I paint from natural light, and the light here is always good,” Del Deo says. “At night, I read, draw, do watercolors — imaginative stuff.”

There are layers to his studio — corners filled with bric-a-brac, furniture, easels, books, old reel-to-reel tapes, odd jars filled with brushes, and two expressive mannequins from the 1850s, inherited from painter R.H. Ives Gammell. And then there’s the art: canvases filed into racks, deep piles leaning against the walls.

“Right now, it’s chaotic because I’ve got to finish this painting that I started 40 years ago,” he says, pointing to a large canvas in the middle of the room. It is The Temptation of Saint Anthony — a pictorial frenzy of harlots, demons, and animals — based on the novel by Gustave Flaubert. “It’s a marvelous book to read, full of imagery in words,” says Del Deo.

The painting is so large that, with his physical limitations, Del Deo can no longer reach the top. “We’re going to devise a ramp for me to get up to be safe, and get me a harness so I don’t fall,” he says.

In front of it is another small easel with a nearly complete portrait. “I love to paint my friends,” Del Deo says.

“I come to the studio every day with no preconceived idea of what I’m going to do,” he says. He may be influenced by where the light is falling or “some thought in my head, and I pursue that, but I keep my mind as fresh as I can. That’s what I’ve done for a good 40, 50 years now.

“My painting habits were formed by my time with Hensche,” Del Deo continues. “I clean my palette every day. I clean my brushes every day. I set my palette up in the same way Hawthorne did it.” These routines and rituals define his practice. “I’m a general painter — everything and anything. I do a landscape one day; I’ll do a portrait the next.

“This thing we call art, it’s not anything separate from life,” says Del Deo. “It is life seen through the efforts of an individual. You’ve got to keep your eyes open, and you’ve got to respond to things. Art is life, and life is art, really.”