What happens when you put maps in an art museum? First, one starts looking at them as art. A 1647 map depicting New England and New Netherland, for example, has drawings of local fauna: deer, foxes, bears, beavers. A colorful cartouche is crowned by the Dutch coat of arms.

One also starts looking at them historically. Critically. Flanking the cartouche are two Native Americans, rendered in a European style. Off the coast are wooden canoes. The land is labeled with familiar but Dutchified names: “Morhicans,” “Pequatoos,” “Manatthans.” The map is just further evidence that the Europeans, in fact, stole this land.

These are the sorts of realizations that occur in “cARTography: Envisioning Cape Cod.” The exhibit, on view at the Cape Cod Museum of Art in Dennis through Oct. 3, has four elements: the historic maps themselves, two art deco murals, an exhibit on Wampanoag history, and an installation by Mark Adams.

Though located up Cape, the exhibit has Outer Cape connections. It is curated by Samuel Tager, executive director of the Provincetown Public Art Foundation. Previously, Tager worked in the museum collections at Harvard University. Furthermore, Adams — a cartographer for the National Park Service and an artist — is represented by Provincetown’s Schoolhouse Gallery. The original ink-on-Mylar artwork on which the installation is based is currently on view there.

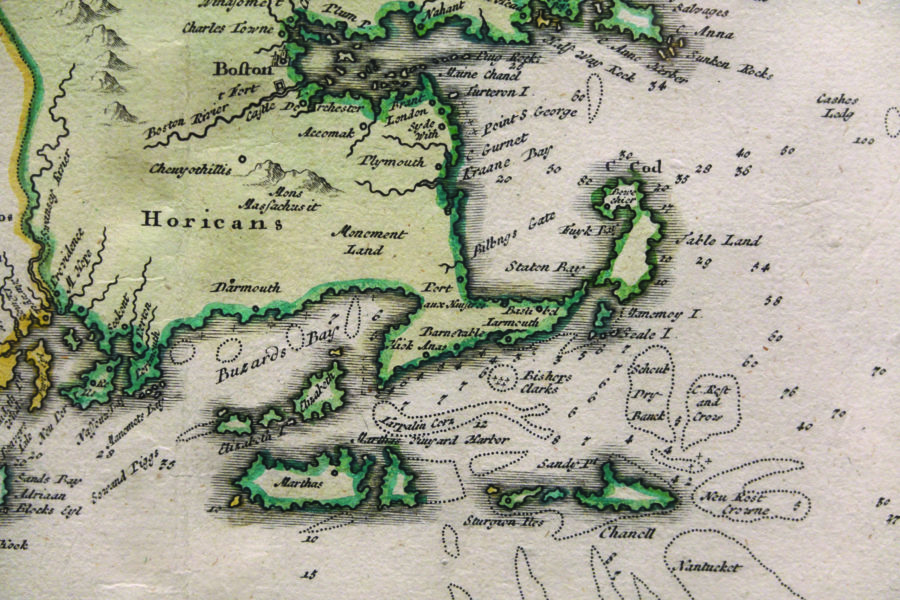

Entering the Hope McClennen Gallery, a visitor finds the peripheral walls covered with maps from the collection of Orleans resident David Garner. They date from the 16th through the 20th centuries. One of the earliest is a 1561 map by Girolamo Ruscelli. Though Cape Cod is absent from this map, it is interesting to see a Venetian’s interpretation of the Eastern coastline. There is an emphasis on canals. Indeed, many of the maps in the exhibit say more about their creators than about the land itself. John Smith’s 1635 map of New England contains a large, distinguished portrait. Henricus Hondius’s 1631 map of the Americas shows shipwrecks and sea monsters.

The museum labels are expertly written by Joseph Garver, curator emeritus of the Harvard Map Collection. Many effectively pull in the Native perspective. In one label, accompanying Samuel de Champlain’s 1613 surveys of Native American settlements, he writes, “As colonization advanced over the next century, indigenous people were expected to sacrifice their land, their rights, and their livelihoods for the dubious honor of being ‘civilized.’ ”

Many of the maps have environmental significance. Johann Baptist Homann’s map of New England, dating from around 1716, shows Jeremiah’s Gutter, a passage that connected the ocean to Cape Cod Bay near the Eastham-Orleans town line, where the Route 6 rotary is now. There are also survey maps comparing the Cape coastline between 1848 and 1888. These can be compared to modern day surveys, with our new knowledge of global warming. Some speak to tourism, such as Coulton Waugh’s cartoonish 1926 map of Cape Cod.

Above the doorways of the Hope McClennen Gallery are two enormous art deco murals from the collection of Jon and Eliza Lewis. These used to adorn a theater in Hyannis but haven’t been seen for 50 years. Though they relate tangentially to the theme of “voyage,” depicting ships, lighthouses, and a stylized Cape coastline, they get a bit lost.

In counterpoint to the maps is “ ‘Our’ Story: 400 Years of Wampanoag History,” a travelling exhibit presented by Smoke Sygnals and Plymouth 400. Highly informative, it consists of museum text and video recreations. One highlight is a map tracing the roots of the Wampanoag territory in the 17th century. The only drawback is that “ ‘Our’ Story” is not as aesthetically pleasing as the hard-to-compete-with maps. There is also a distance separating these two elements — it is partly left up to the museumgoer to make connections.

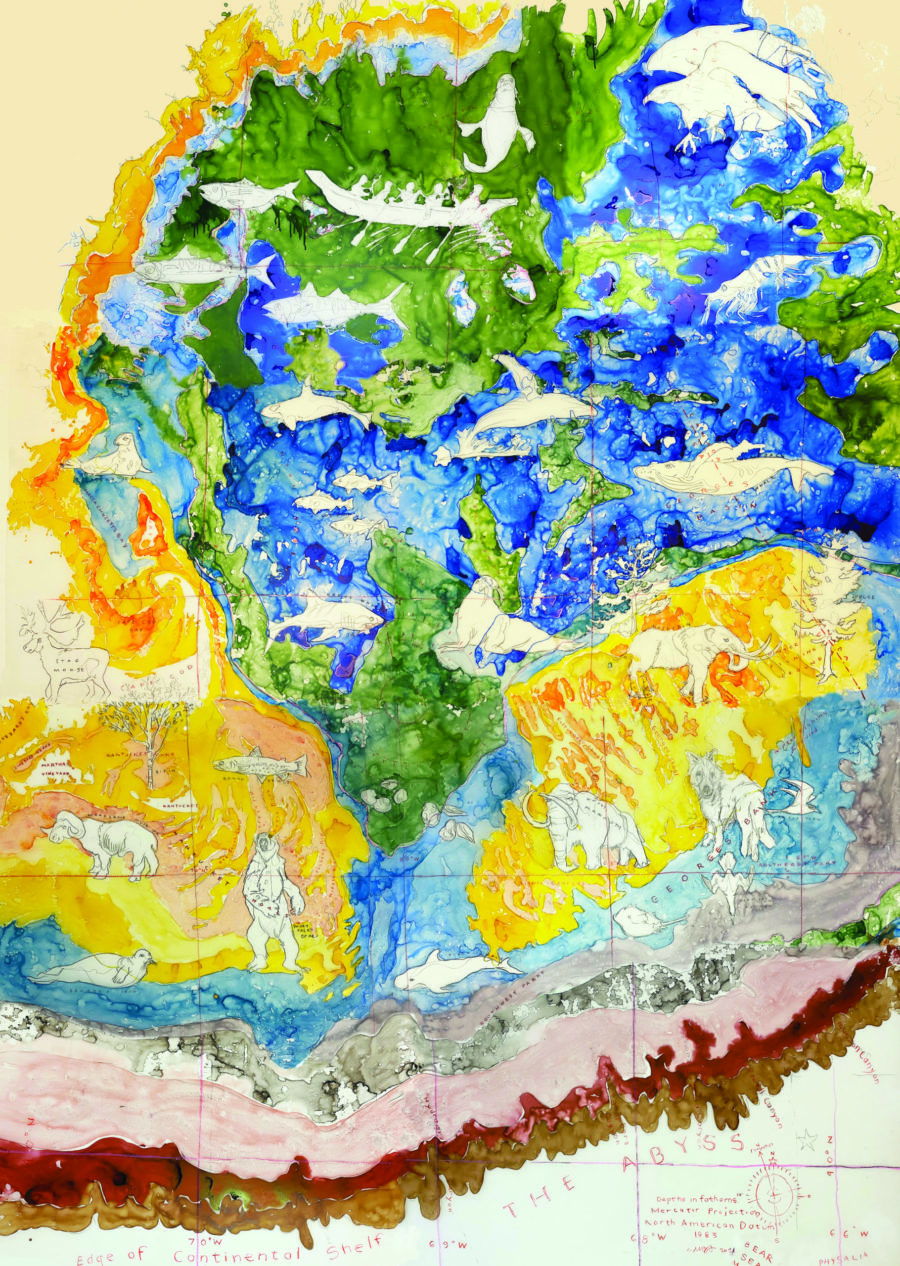

What begins to tie the exhibit together, however, is Mark Adams’s installation. Located in the vestibular Ocean Edge Gallery, it consists of a floor map depicting George’s Bank as it was 11,000 years ago, when it was part of Cape Cod’s land mass. This was when Native people first arrived, long before European settlements. Sea level was 200 feet lower than today, and megafauna roamed the land. On the walls, Adams has drawn constellations of woolly mammoths and whales. There is also a painting of Moshup, the giant who, according to Wampanoag legend, shaped land masses.

The floor map was achieved by enlarging and printing Adams’s original ink-on-Mylar artwork on vinyl floor material, so that museumgoers may step on it. The result calls to mind Adams’s 2017 exhibit at the Provincetown Art Association and Museum titled “Expedition,” which included a floor map of the Gulf of Maine. Walking on art is an intimate experience that also gives the museumgoer the unusual sensation of trespassing — in this case, with the artist’s permission.

Off the Map

The event: “cARTography: Envisioning Cape Cod”

The time: Through Oct. 3; Wednesday through Saturday, 10 a.m. to 4 p.m.; Sunday, noon to 4 p.m.

The place: Cape Cod Museum of Art, 60 Hope Lane, Dennis

The cost: Adults $10, students $7