David W. Dunlap’s Building Provincetown is an ongoing project with a worthy aim: to create a comprehensive history of the town — that is, its residents, year-round and part-time, and all the astonishing work and eccentric play they are known for. But it’s organized in a counterintuitive way.

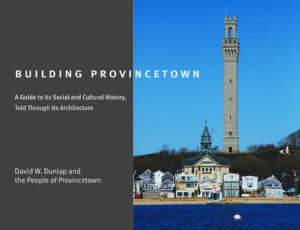

Dunlap, a veteran New York Times journalist and author, has chosen to tell people’s stories by cataloguing the buildings they inhabit. That’s right — buildings: homes, stores, inns, galleries, studios, restaurants, bars, factories, banks, schools, docked ships, dune shacks, stables, and any other structure that illuminates the lives of those within. In short, the organizing principle for Dunlap’s 2015 book, Building Provincetown: A Guide to Its Social and Cultural History, Told Through Its Architecture, and the websites he has developed as a byproduct — buildingprovincetown.wordpress.com and buildingprovincetown2020.org — is, simply, a street address.

“That’s the happy discovery of research,” Dunlap says, speaking from his apartment on the Upper West Side of Manhattan. “You start diving into each parcel and you find most all of the layers that constitute the entirety of the town are represented in one building.”

The book Building Provincetown, originally published by the Town of Provincetown and funded by a Community Preservation grant, is being re-issued this week in a new, full-color edition by the Provincetown Arts Press. The text is largely the same — Dunlap says he tweaked his preface a bit, and there’s a new introduction by Cape-based architect John DaSilva — but now, the thousands of photographs that accompany the 600-plus entries will be that much more vivid in color. (To order a copy, go to provincetownarts.org.)

The wealth of material in the book — all of it thoroughly researched facts and lore, from published and archival sources and the recollections of locals — can take you on an alphabetical journey through addresses that lovers of Provincetown will find addicting. Did you know, for example, that 135 Bradford St., where Scott Allegretti’s dental practice is now located, was the first home of the Fine Arts Work Center, from 1969 to 1972? That the large warehouse-like building at 241 Bradford St. was built during World War II as part of the Naval Mine Test Facilities? That Club Purgatory at Gifford House, 9-11 Carver St., saw a production of Amiri Baraka’s Dutchman in 1966, starring Norman Mailer’s wife, Beverly Bentley? That 8 Johnson St. was the summer home of artist Edith Lake Wilkinson, before she was needlessly committed to a mental hospital?

And although there’s a fair amount of discussion of architectural detail, in the end, it’s usually just a portal to a very human story.

Dunlap’s interest in Provincetown began with his first trip here in 1989 with a former boyfriend who was offered a week at a friend’s house in the West End. Dunlap and his husband, author Scott Bane, got together in 1994, and they returned here time and again, falling in love with the town’s cultural richness and remarkable history. Being a relentless reporter and researcher, Dunlap read up on as much as he could.

“There were lots and lots of books about Provincetown, but I couldn’t find anything equivalent to the AIA Guide,” he says, referring to the American Institute of Architects and its indispensable guide to New York City buildings. “That’s what was missing in Provincetown. After a number of years of trying to find such a thing, or waiting for such a thing to be published, I said, ‘Dunlap, why don’t you do it?’ ”

The effort began in earnest with a blog. “In 2009, I opened buildingprovincetown.wordpress.com for business, and started posting individual articles,” says Dunlap. “That introduced people to the project — that this strange guy was chronicling every structure in town.”

The website grew to 2,000-plus entries, far more than could fit in the book. And once Building Provincetown was published in 2015, Dunlap began to realize that the website might be an end in itself. “Because of its advantage of limitless word count, limitless images, cross-referencing, and, most important, input from readers, the website was an ideal way to perpetuate the Building Provincetown project,” he says. “It instilled in me the idea that I could do all the buildings in Provincetown, something you couldn’t possibly do in a book.”

Looking forward to 2020, and the 400th anniversary of the Mayflower landing here, Dunlap decided to start anew, and he created buildingprovincetown2020.org, using all new material. “I’m taking as long as I need to take with each individual building,” he says. “I start by throwing in the history I’ve already written. I’m really digging into old atlases, deeds, newspaper clippings. And I’m trying to accommodate the Wampanoag presence.”

The 2020 deadline came and went, and Covid arrived, and there was still a long way to go. Dunlap jokes that if people in the future ask why “2020” is part of the website domain name, “I’ll say it’s about looking at Provincetown with 20/20 hindsight.”

He turns 70 next year. “If actuarial tables are to be believed, I’ve got about 14 years to do this project,” Dunlap says. “I could be at it till I drop dead at the computer.” That’s not really a deterrent. “Right now, I’m working on 190 Commercial St., a.k.a. Spiritus Pizza. It was once owned by Max Berman, an optometrist, who had his practice there. His wife, Anita, was a guidance counselor at Provincetown High School. If you look at Spiritus closely, you can see that there’s a Cape Cod house screaming to get out.”