The pandemic has surely dealt a blow to jazz, which, like a mythical beast, is prone to periods of obsolescence during which nearly everyone in the kingdom declares it dead. With every gig taken off the calendar, every jam session postponed indefinitely, America’s music receded into the shadows once again. The virus also took some of its greatest sages: Lee Konitz, Wallace Roney, and Ellis Marsalis. Despite these setbacks, the friendly dragon of jazz flew high over the Newport Jazz Festival this year — from Friday, July 30 through Sunday, Aug. 1 — and I was there to see it.

Since the mid-1950s, Newport, R.I. — a city just two and half hours from Provincetown — has been a special place for jazz music. In the first decade of the festival, performances by Duke Ellington, Ella Fitzgerald, Billie Holiday, Thelonious Monk, Miles Davis, and John Coltrane generated all manner of jokes, legends, and breakthroughs. In 1956, for example, Ellington and his orchestra recorded a live album that relaunched them after years of bad luck and meager earnings. Ellington later declared, “I was born at the Newport Jazz Festival on July 7, 1956.”

Part of the festival’s appeal is its location. Fort Adams, which overlooks Narragansett Bay, was first constructed in 1799 under President John Adams and rebuilt after the War of 1812. The city itself is known for its Gilded Age “cottages” — colossal mansions that today function largely as tourist meccas. In 1963, you could drive from the Vanderbilt summer stronghold to a John Coltrane show in under 15 minutes.

Jazz has undergone many transitions since that era. In ’69, the festival hosted rock artists Frank Zappa and Led Zeppelin, challenging the limits of “jazz.” Then, in ’71, thousands of non-ticketholding youths who had been camping nearby stormed the gates and destroyed the stage. Through the rest of the ’70s, the “Newport Jazz Festival” was held in New York City. Around that same time, the genre saw a decline in popular interest. The festival returned to Newport in ’81, where it has remained since.

This was my eighth year at the festival, and it was as lively as ever, despite the wearing of many masks. We sat in front of the main stage as trumpeter Christian Scott aTunde Adjuah and his band played. Adjuah’s tone at times recalls Miles Davis’s. As Miles did in the ’80s, Adjuah fuses several styles into a sound that is at once vast, kaleidoscopic, and occasionally reminiscent of hotel lounge music.

The wind was high and, looking out at the nearly 180-degree view of the bay, we saw sailboats heeling at high speed across the horizon. Framed by this scene, people milled about in the beer garden, holding their hats to their heads. Some squinted at the massive LCD to the left of the stage, which displayed a close-up of the pianist’s fingers.

Next was alto saxophonist Kenny Garrett’s performance at the quad stage, inside Fort Adams. It is open to the air, but its high walls create a womblike feeling of a separate world. Even after all these years, Garrett sounds as if he’s teetering on the edge, playing at his limits.

On Sunday, things really started to heat up. I sweated profusely in the sun, enjoyed several Del’s soft frozen lemonades (a Rhode Island specialty), and sat for hours of blistering jazz. The early morning brought the “Vibes Summit,” spotlighting three vibraphonists: Joel Ross, Warren Wolf, and Sasha Berliner. If I had to pick a winner (“summit” really means “contest” in my mind), I’d go with Ross, king of the vibes.

A bit later came the Jazz Gallery All-Stars. The Jazz Gallery is a midtown Manhattan spot featuring the more modern flank of the city’s jazz scene. Its motto is “Where the future is present.” The band included guitarist Charles Altura (known not only for his virtuosity but for his emo haircut), pianist Gerald Clayton, saxophonist Melissa Aldana, and Joel Ross back on the vibes. Aldana, who won the Thelonious Monk Competition a few years ago, is one of the greatest living saxophonists, so it was almost overwhelming to see her playing with Ross.

Last but not least, 83-year-old saxophonist Charles Lloyd graced the stage, playing so well that I forgot about the heat and entered a realm of tranquility and spiritual geometry. Lloyd, a living legend, had assembled a band of musicians who played with freedom and ease.

At one point, Lloyd mentioned that he’d driven cross-country with Chico Hamilton to play Newport in ’61. But there was no Newport Jazz Festival that year, only the knockoff “Music at Newport” put on by a rival for-profit company. (NFF, the original and present-day festival sponsor, is nonprofit.) It was probably all the same to a young Charles Lloyd, but the distinction is key: Newport Jazz, despite the nearby mansions and yachts, has always been about music and not money.

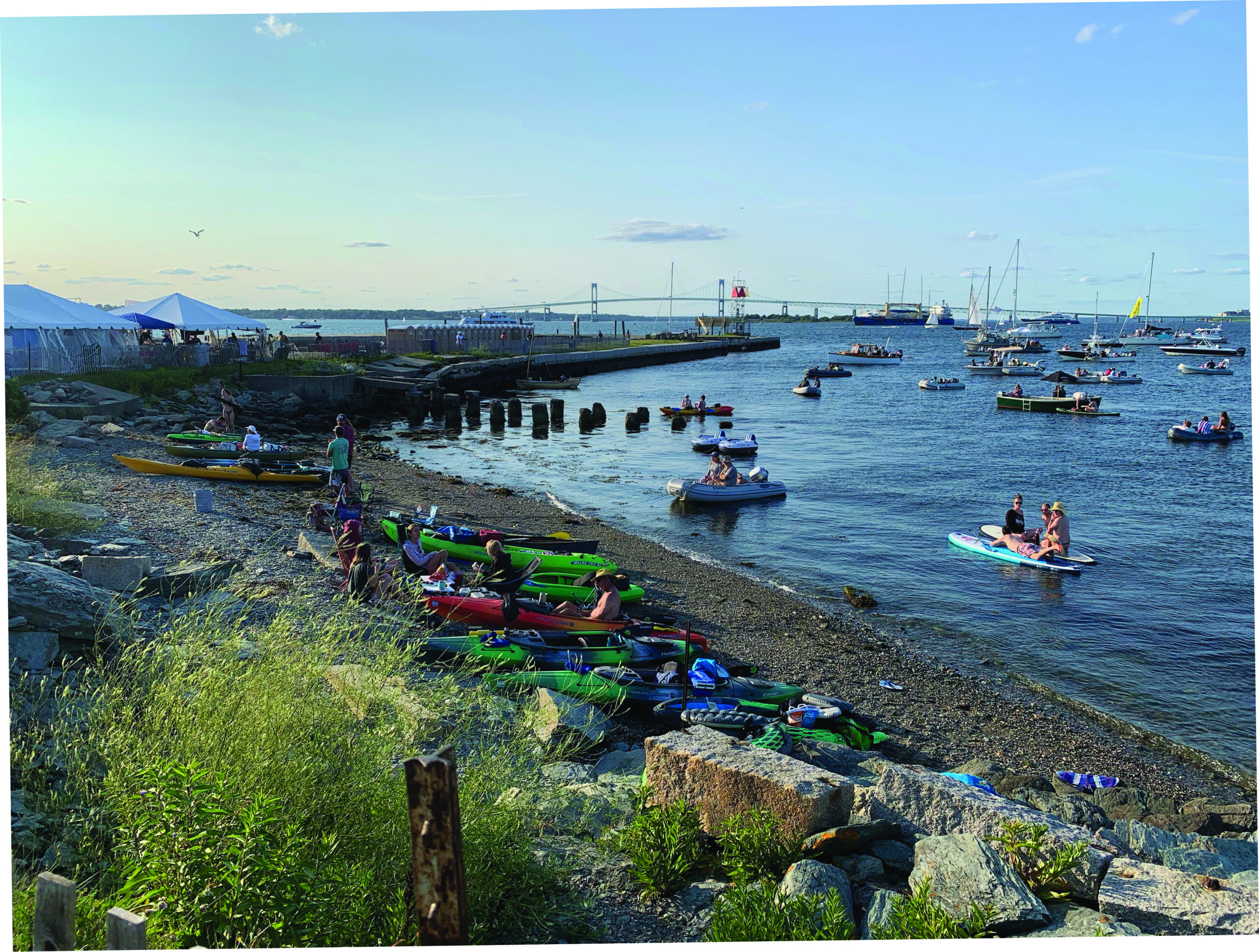

As the day was wrapping up, I went for a walk and enjoyed a final Del’s as I searched for a sunset viewing spot. I spotted a shirtless man smoking a cigarette and dancing on a jetty just beyond the festival limits. A few kayaks were pulled up on the beach beside him. I toasted him with my lemonade and asked if he’d bought a ticket.

“Nah,” he said, pointing to his ear, “but I can hear it.” Behind him, dozens of boats that had dropped anchor bobbed slightly as their passengers swayed to the music.