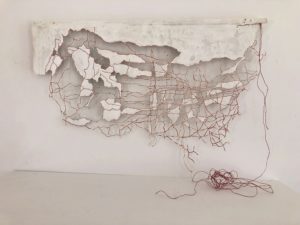

“My work is always somehow connected to the body, to something that feels intimate,” says Janice Redman. In her Truro studio, she works surrounded by sculptures in various stages of completion, and shelves overfilled with objects collected over decades. Her pieces — a purse made of dehydrated bees wrapped in linen; an oar riddled with carefully drilled holes — beckon the viewer with an intensity that is startling, complex, and inescapable.

“When I encountered Janice’s work years ago, I was overcome by the beauty and the quietness of it,” says Susie Nielsen, owner of Farm Projects, a gallery in Wellfleet. “She does so much for the viewer in the way her pieces invite, even force you to go into your deeper places. When you see her work, you can’t not think about it.”

Nielsen will be showing Redman’s sculptures at Farm Projects through Aug. 31. In addition to a reception on Saturday, Aug. 21 from 6 to 8 p.m., the gallery will host a conversation between Redman and writer and naturalist Elizabeth Bradfield on Aug. 28 at 5 p.m. Bradfield and Redman have been meeting regularly to create — side by side, in the same space — for over a decade. “Although we work independently, we have very concentrated energy together,” Redman says. “The trust, support, and inspiration we share has kept me afloat and connected.”

Redman’s artistic process is both intuitive and deliberate. “I meditate every morning for 40 minutes,” she says. “After I’ve meditated, I look around in my studio until something speaks to me. I find my way into the work emotionally by taking in what is around me until I discover an interconnectedness between the objects. They speak to one another, and I meet that conversation with wonder.”

Redman practices patience and observation over time — sometimes our deepest-felt memories take years to resurface. She allows the objects she has brought home, often from flea markets, as long as it takes to speak to her. “I have to give them the space and the time to mellow and to mature,” she says. “The minute I start to feel like I’m imposing on the work, I have to stop and wait.”

Redman’s sculptures are imbued with recollections of growing up in a small village in South Yorkshire, England. “When I think about my childhood, the moments that touched me most, that lingered because they were meaningful, were always incidental,” she says. “It’s interesting to realize how often what is incidental actually feels most important. Those are the moments I hold onto in my body. When I do my work, I feel connected to these memories in a way that feels organic and helps me process them.”

Redman was brought up in one of the many box-like houses built in England in the ’50s and ’60s, one she describes as being “way too clean and orderly.” Her mother was a seamstress and lacemaker; her father was a teacher. Expressing emotions was discouraged and the “making” of objects focused strictly on functionality. “My dad played the trombone in a brass band. He restored antique clocks, kept bees, and made homemade wine,” says Redman. “My mom taught me to sew at a very early age. So, both my parents used their hands in very practical ways.”

Though her brother was labeled the talented one, Redman surprised her parents by going to art school. She earned an M.F.A. at Ulster University in Belfast, Northern Ireland, and went on to do the Core Residency Program at the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston, Texas.

In 1992, Redman arrived in Provincetown as a fellow at the Fine Arts Work Center. “After Houston, I thought I was done with the United States,” she says. “But as soon as I came to Provincetown, I felt I had come home.” Redman stayed at FAWC for a second year and eventually met painter Rob DuToit. They married and settled in an old Cape Cod house in Truro, where Redman lives and works surrounded by rambling vegetable and flower gardens, bees, and chickens.

Redman’s acts of sewing, mending, wrapping, gluing, and drilling holes into everyday objects explore hidden interior spaces with the intention of revealing, protecting, and ultimately healing childhood emotions that weren’t talked about. Her fascination with filling, turning inside-out, and emptying bags and purses — a recurring theme in her work — is, for example, “about what each of us carries around in our life — what we choose to hold close, how heavy or how light do we move through our life, what load are we carrying.

“The phrase ‘making amends’ has always stayed with me,” Redman says. “And with the drilling of holes, I always have this feeling of wanting to make space — to give the piece air to breathe and ultimately dissolve. When I was drilling holes in the plaster, I was reminded of sucking on a sugar lump as a child and the sensation of it dissolving on my tongue. A strange, visceral sensation.”

By deconstructing an object’s intended use, Redman’s sculptures subvert functionality. “I make objects that don’t have any practical purpose, but they have meaning, and are always directly connected and integral to my life,” she says. “I am putting myself on the line, holding vulnerability out there. I am not wanting to hide what is inside but look at it and allow it to have a voice.”

Stitch in Time

The event: Works by Janice Redman

The time: Thursday, Aug. 19 through Aug. 31; reception Saturday, Aug. 21, 6 to 8 p.m.; conversation Saturday, Aug. 28, 5 p.m.

The place: Farm Projects, 355 Main St., Wellfleet

The cost: Free