As a tale of family dysfunction, Tennessee Williams’s The Glass Menagerie is shrouded in the cloud of memory. The play, which opened on Broadway in 1945, was Williams’s first critical and box-office success. He had spent summers in Provincetown, and it’s claimed that he wrote the play here — renting a room and thinking back on his post-college days in St. Louis in the 1930s, when he lived with his mother and impaired older sister in the shadow of his alcoholic and largely absent father.

David Drake, the artistic director of the Provincetown Theater and the director of its new production of The Glass Menagerie, introduced the performance last Tuesday in the outdoor Playhouse in the Parking Lot by noting that it was time to bring this great work back to its source on the Outer Cape.

Williams, in his stage directions and in the opening soliloquy of his narrator and personal stand-in, Tom Wingfield, makes clear that what he is putting forth in The Glass Menagerie is not something real or imagined, but an evanescent shred of a time past. It is the most autobiographical of his plays, and quite stark. It’s filled with the poetic musings and symbolism that are signature Williams, but the melodrama — so familiar in his great plays of the ’40s and ’50s — never comes to a boil in this play.

Matching that impressionistic mood, scenic designer Ellen Rousseau has covered the set with sheer, billowing white fabric. When these sheet-walls are lit from behind, one can make out the giant outlines of animals that are Laura Wingfield’s glass figurines — a unicorn and a giraffe. They also appear in the foreground, in miniature, on a small table lit from below.

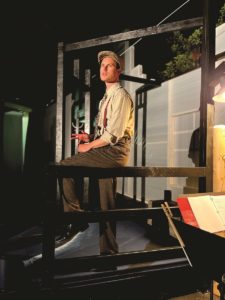

Laura walks with a limp due to childhood afflictions. In her late 20s, unemployed and living in a fantasy world, she’s infantilized and emotionally paralyzed by her fears and isolation. As played with touching fidelity by Racine Oxtoby, she resists any attempt to alter her stasis, shielding herself from any real hope or disappointment. She is Tom’s older sister, but, in the absence of a father, he is the breadwinner and alleged man of the house. Todd Flaherty, as Tom, is peevish and unsentimental, seething in frustration. Hating his factory job and longing to be a writer, he escapes nightly to the movies to dream of a different life.

At the center of this family dynamic is Amanda Wingfield, the domineering mother who yearns for the decorum of Southern gentry and basks in the memory of her youthful beauty and charm. In this production, Jarice Hanson plays Amanda with passion and sensible restraint: though full of broken dreams and rage, she’s a pragmatist at heart. Amanda has elements of archetypal Williams madwomen — Blanche DuBois’s Southern belle delusions and Violet Venable’s implacable will — but economic survival is her bottom line. She knows that, without a job or a husband to provide for her, Laura will never be able to take care of herself. Upon learning that Laura has dropped out of secretarial school, she implores Tom to bring a “gentleman caller” home to meet his sister.

Tom complies, and invites his supervisor at the factory, Jim O’Connor, to dinner, setting in motion the main dynamic of the second act and its tragic conclusion. Jim, as played by LeVane Harrington, is brash and immature, so seduced by the fact that Laura knew him and had a crush on him in high school that he plays into her fantasies until it’s too late.

Amanda, at one point, talks about the “tyranny of women,” but the real tyranny that the play elucidates is the cage that most Depression-era women were locked inside: except for their ability to manipulate men or adapt to men’s needs, they are powerless to decide their destiny or defend themselves from abuse.

Drake directs this domestic turmoil with a contemporary consciousness, brushing away the delicacy and histrionics of previous productions. It is a memory play, after all — a look back to the source of pain and guilt. Drake and his cast emphasize the pettiness and futility of each character: Tom’s surliness toward his mother, Laura’s phobic reflexes, Amanda’s blind determination, and Jim’s empty pride in past glories and future prospects.

It’s a fresh take on a classic, reclaimed for Provincetown by its home-grown company (Oxtoby and Harrington are Cape natives). Our stumbling emergence from Covid gives the play urgency, and our polarized politics give it moral weight. See it now, for a dose of the insight and redemption of live theater.

Through a Glass, Drake-ly

The event: The Glass Menagerie, by Tennessee Williams

The time: Monday through Thursday, 7 p.m.; through Sept. 2

The place: Provincetown Theater’s Playhouse in the Parking Lot, 238 Bradford St.

The cost: $45 to $55 at provincetowntheater.org