“I spent most of my early art practice and young adult life trying to escape from the inherited social constraints of Blackness,” says textile artist Qualeasha Wood. “My perception of what it meant to be Black was always skewed by the notions and stereotypes of what Blackness is supposed to look like and be. And I think that’s something that I learned from structures of whiteness, but also from other Black people who tried to teach me how to behave or assimilate.”

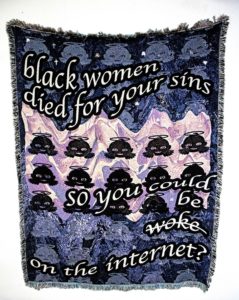

Wood’s work, which has been described as bold and provocative, at once resists and embraces these stereotypes, she says, “as an act of defiance.” An act, she adds, that has allowed her to push back and gain autonomy: “Autonomy to choose how I’m going to exist in a space or portray my Blackness or a Black figure in a specific way. My intentions aren’t about shock value — some people tend to think they are. My goal is having freedom of expression.”

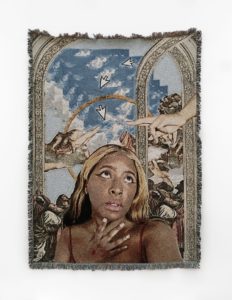

At only 24, Wood is already an emerging artist to watch. Her tapestry titled Black Madonna — Whore Complex is on the cover of the May/June 2021 “New Talent” issue of Art in America. Wood has also been chosen as one of Louis Vuitton’s 200 “visionaries” to take part in the French designer’s bicentennial.

Wood will be showing new works at Gaa Gallery in Provincetown from Friday, Aug. 6 through Aug. 29, alongside fellow fiber artist Kaylie Kaitschuck. These hitherto unseen pieces by Wood are part of a series of tuftings (a type of textile where yarn is inserted into backing fabric) that she started in 2020.

“Kaylie’s work is all about nostalgia and using childlike symbols and drawing aesthetics to tell a story,” says Wood. “I feel that her art pieces align well with my tuftings, which talk about complex situations in a subtle, playful way.”

Wood, who holds a B.F.A. in printmaking from the Rhode Island School of Design and an M.F.A. in photography from the Cranbrook Academy of Art in Bloomfield Hills, Mich., didn’t expect tuftings to be a medium for her artistic expression. She got the inspiration when she was visiting her parents in Long Branch, N.J., where she was born and raised, during winter break just before the pandemic.

“I was looking through family photos from my childhood and noticed that my parents had used rugs and fuzzy blankets with images of Looney Tunes and other cartoons as wall and door coverings,” Wood says. “When the pandemic hit in March and everything shut down, I wanted to try something different. I thought tufting for me was going to be a fun hobby. You know, everybody needs their escape methods,” she adds, laughing.

Wood found that her tuftings, far from being a simple hobby, were drawing from her childhood memories to explore themes of Blackness, trauma, and the passage of time. “I was asking myself: how do I make a rug that is in the realm of cartoon and talks about these critical issues?”

When Wood showed her first tufting to Kendra Jayne Patrick, the New York City gallerist, her reaction persuaded Wood to keep going. “As a child, the most engaging moments in cartoons are also the scariest,” says Wood. “I realized that the tuftings play in this interesting space that creates a lot of tension between playfulness and danger, or even violence.”

Many of Wood’s first pieces draw on traumatic childhood memories: near drowning, sexual assault by another child, listening to her mother’s stories of growing up in Alabama during the tail end of segregation and feeling unsafe going to school. “Memory and time — and the blurring of what was actually real and how we see an event when we look back at it — are so powerful,” Wood says. “There’s a skew in perspective that makes me wonder: Is this an accurate memory? Or is this just something that I’m projecting onto the image?”

Wood’s tuftings are fun and inviting on first view, but then reveal unsettling elements that provoke questions. Perhaps the most evocative of these are the pairs of faceless eyes, staring back at the viewer, that recur in some of the works. “When I first started getting into the eyes, they were always a reference to a shadowy figure that I didn’t want to make appear fully,” Wood says. “I made a piece called After Dark, for example, that was about the fear you can feel as a woman walking home alone at night and feeling watched.”

As Wood continued work on her tuftings into 2020, she realized she was entering a conversation about trauma, voyeurism, bystanders, and accountability. “I think Black artists in general, and women especially, struggle to find ways to talk about trauma in their work in a way that feels productive and safe,” Wood says. “It’s very difficult to talk about trauma, but it’s also very important. We watch things happen — a violent video on social media, or an incident on the street — and are paralyzed by fear, but also a weird layer of excitement. The tuftings, and the eyes in particular, have become a way to engage viewers — and also implicate them.”

Moral Fiber

The event: Works by Qualeasha Wood, alongside ones by Kaylie Kaitschuck

The time: Friday, Aug. 6 through Aug. 29

The place: Gaa Gallery, 494 Commercial St., Provincetown

The cost: Free