One day in June, my wife and I left our cottage to walk straight out the mouth of the Herring River in Eastham. Low tide had exposed acres of sand in Cape Cod Bay. Overhead, willets darted and called.

In the Herring’s last meander, a plank lay at the high-tide line. I picked it up and plunged it into the sand. The soggy flotsam was suddenly an upright human form. A sundial. A place marker, announcing the entrance to the river, or the exit to the bay. It had a presence, and seemed to signify something, however ambiguous and eye-of-the-beholderish.

There’s a tribe of us who pull this stuff on the shorelines of the Outer Cape, making impromptu sculptures with whatever’s lying on the beach or bundled in the wrack. A lot of excellent fine art is made and displayed on the Outer Cape. This is literally outsider art, made with whatever washes ashore. We’re opportunistic bricoleurs, reassembling the dismantled world’s random, story-rich parts into a new relationship with each place.

When Thoreau walked the Outer Cape’s ocean beaches, shipwrecks were both tragic events and recycling opportunities. He wrote, “After an easterly storm in the spring, this beach is sometimes strewn with eastern wood from one end to the other, which, as it belongs to him who saves it, and the Cape is nearly destitute of wood, is a Godsend to the inhabitants.”

There were limits, though, to what a “wrecker” could salvage or claim. “Wreck masters” were appointed to look after valuable property. But, for the most part, a wrecker could appropriate a gathered collection of debris, Thoreau reported, “by sticking two sticks into the ground crosswise above it.”

I thought about such claims of ownership last fall when I read the Independent’s article about Drew Carnelli and his sculptures on the beaches. He was frustrated and baffled when people dismantled the fences and freestanding creations that he assembled from found objects like wood and rope. And that reminded me of the puzzlement I felt when I discovered someone had knocked down about a dozen of my rock cairns.

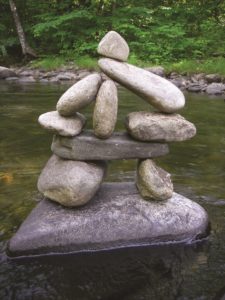

It was an obsession of mine one summer, about 15 years ago, in the midst of cancer treatments and a bleak prognosis. To come to an agreement with death, I first had to make a new agreement with life. I see that now. Then, I was simply compelled to coax a provisional stability from balanced rocks, some of them 12 stones high. I built them in the water that falls down a ravine next to our home in Vermont.

They were meant to be ephemeral — an invitation to gravity or the periodically rising waters of the brook. I cradled each stone like a baby, but made the cairns quickly, without pausing for judgments. “Empty your mind,” I said. “Keep moving.” Every time it rained, the brook rose up and knocked some down, and it always made me smile.

Then I built some along the road next to the brook. A lot, actually. One day, I took the dog for a walk up the road and found many of them knocked down. On the other side of a deep pool in the brook was a large, broad-faced boulder upon which I had stacked some rocks. Now they lay in the bottom of the pool. Across the boulder were chalked the words “Jesus is Lord.”

There was something Cyrillic about the “L.” It pointed to a new resident on the hill, from Eastern Europe. I called and spoke with her husband, an American. He explained that she had been raised to believe such things were the devil’s work. She acted impulsively, from fear and religious fervor. She is shy to begin with, and was embarrassed about what she had done. She avoided me.

We finally spoke. I told her I admired her for acting on her beliefs. That I intended the cairns to be art, to represent what is transitory about life, to remind us of what we both know is eternal.

That last part I hadn’t realized until the words came out. It was only after her passionate response to the work — and my fumbling attempt to articulate the divine in her second language — that I saw this for what it was. I had alchemized fear of the future into taking joy in the present, in what is precarious, which is to say, almost everything.

We’re born into mysteries. Stand in everyday surf and improvise a life from what the waves bring. I’m four years past a cancer expiration date. That punky standing plank in Eastham, that upright human form, is a creature of will and a plaything of the tides, and destined for hands other than mine.

Richard Ewald lives in Wellfleet and Westminster West, Vt.