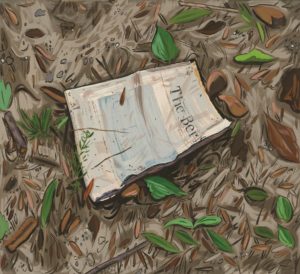

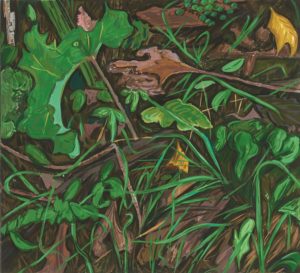

A torn newspaper lies among fallen leaves. Tender weeds sprout inside the imprint of a coiled garden hose. “As a painter, there is no patch of ground that is uninteresting to me,” says the artist Josephine Halvorson. “I could walk anywhere and see something in every step that I take. There’s a whole world, a whole universe right there in front of us.”

In her series titled “On the Ground,” painted between 2018 and 2020, Halvorson invites the viewer to join her in studying the earth we walk on. Each painting registers a patch of ground, revealing hidden layers and possible meaning. The frames include ground-up site materials such as rocks, clay, glass, iron, and plastic, anchoring the work in the place it was made.

“My practice is about cultivating a certain kind of attentiveness,” Halvorson says. “I think about taking time or making time to look at the world around you, like when you were a child and didn’t necessarily have a sense of relative duration but were absorbed in something you saw and wanted to explore.”

Five of Halvorson’s “On the Ground” paintings will be on display at Gaa Gallery from Thursday, July 1 through Aug. 1, alongside works by Esteban Cebeza de Baca.

“This exhibition is meaningful,” she says, “because Provincetown is where I first learned to paint.” As a high school student, Halvorson took classes at PAAM and the Cape School of Art. A plein-air painter to this day, she remembers being taught “to paint the color of light rather than the local, or nameable, color of something you’re looking at.”

Raised in Brewster by two artist parents, Halvorson discovered painting at a young age. “My mom let me experiment with some of her oil colors,” she says. “I remember that I liked how the paint moved, I liked the colors, and I liked the smell. It was an instant sense of recognition with the medium.”

Now living in Western Mass., Halvorson received her M.F.A. from Columbia University in 2007 and is a professor and chair of graduate studies in painting at Boston University. She was recently awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship.

Over the past two decades, Halvorson has lived and worked in several of Europe’s cultural capitals. In 2003, she won a Fulbright to Vienna; from 2007 to 2008, she studied art in Paris; and from 2014 to 2015, she was the first American pensionnaire at the French Academy in Rome at the Villa Medici.

Halvorson considers these experiences to have been “a formative art education, not just in the making of paintings, but also in understanding worlds beyond my own experience.” In Vienna, influenced by the work of Egon Schiele, Halvorson painted portraits of immigrants and others who did not fit into mainstream Austrian culture. “Now that I look back,” she says, “I see how I was confronted with my own Americanness and what it feels like when you leave your home culture and redefine yourself in a new cultural context.”

When Halvorson was in Rome, she was geographically close to the migration wave from the Middle East and North Africa. Observing the endless stream of refugees traveling on foot, Halvorson — who had just bought her home in Western Mass. — became keenly aware of what it means to hold claim over the ground you walk on.

“I was already inclined to be a close, attentive looker and thinker, but that skill got honed and developed when I was abroad,” says Halvorson. Drawn to language — “how words carry meaning, and how that meaning develops and changes over time” — Halvorson considers painting to be an act of translation.

Halvorson’s subjects may seem uncomplicated — a brush of bright orange paint on gravel, a half-torn “No Trespassing” sign attached to a tree — but she aims to capture something deeper. “I’m making a painting that represents something in the world, but, in that description, I hope to represent more than what I see,” she explains. “Making the invisible visible is a practice of not knowing — of learning and being receptive to the mystery, wonders, and riddles of everyday life.”

For a while, Halvorson painted each work strictly over the course of one day. Lately, this has become more fluid and adapted to circumstances. “The things I can’t control — the setting of the sun, for example — are integral to my work,” she says. “I see these constraints as an active collaborator. I think about that in my work and increasingly see my paintings as a chronicle of time and of experience.”

Since completing “On the Ground,” Halvorson has turned her attention to objects that preserve memory. In 2019, she was the inaugural artist-in-residence at the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum in Santa Fe, N.M. She spent time in O’Keeffe’s summer home at Ghost Ranch, painting O’Keeffe’s belongings. She will have a solo exhibit of these works at the O’Keeffe Museum later this year.

During the pandemic, Halvorson painted her father’s personal items after his death. By looking closely and with care at objects left behind, she believes hidden traces of a person’s life are revealed.

“Whether it’s a rock on the ground or a book someone once owned or tools waiting to be used again, objects have memories of their own,” Halvorson says. “In my practice, I try to make space for hunches or feelings. Painting is a pretext to follow them to see where they lead.”

Well Grounded

The event: “Five Grounds,” works by Josephine Halvorson

The time: Thursday, July 1 through Aug. 1; opening reception Friday, July 2, 6 to 8 p.m.

The place: Gaa Gallery, 494 Commercial St., Provincetown

The cost: Free