I’ve always best expressed my personal take on life through the movies I’ve watched — a quirk of memory rooted in my media-obsessed consciousness.

For example, there’s a scene in Otto Preminger’s Advise & Consent — a 1962 political thriller that was screened in the auditorium of the junior high school in Fair Lawn, N.J., where I was enrolled — that haunted me throughout most of my teenage years.

The movie was most likely chosen by history teachers at the school because it exposes the sleazy, behind-the-scenes machinations of the U.S. Senate, particularly the anti-Communist viciousness of the McCarthy era. But that aspect of the film wasn’t especially revelatory to me, having been raised in a lefty intellectual home in the ’60s.

The scene that branded itself on my memory involved a senator from Utah, “Brig” Anderson, played by Don Murray, an actor with all-American, sitcom-dad looks. He’s a handsome, virile presence in the movie’s grizzled male ensemble, which includes, memorably, Charles Laughton in his last movie role, as a wily old Southern senator. Ironically, Laughton spent his life in Hollywood tormented by his homosexuality.

Brig, who leads a committee investigating an appointee accused of being a Communist, is being pressured to fall in line for a vote. A threat surfaces — to expose some dirt from his past, when he was in the Army in Hawaii. It involves a man named Ray, whom Brig suddenly decides to visit in New York.

Brig goes to see Ray in a gay bar, the sort of place I had no idea existed at the time. The telltale clues — stylishly dressed men socializing intently with other men — eluded me, but it was abundantly clear that Brig’s past relationship with Ray was fraught and undeniable.

After the meeting, Brig returns to D.C. and, with his wife watching behind him, stares at himself shirtless in the bathroom mirror with a razor. His desolation is palpable. Confronted with a no-win situation, he commits suicide. Though the act takes place offscreen, it’s a shocking, climactic development.

The scene is fiction, from a best-selling Allen Drury novel, but it’s not fanciful: suicides by men arrested during the “lavender” witch hunts of the McCarthy era, weeding out homosexuals from the State Dept., were commonplace.

I saw the movie just as I had begun to recognize my attraction to other boys and men. The feelings of vulnerability and shame arising from that attraction were intense. Other kids experiencing sex for the first time may have felt some shame as well, but that scene in Advise & Consent highlighted the specific and irredeemable stigma of homosexuality.

Until I came out at age 20, I struggled with my desires and insisted they couldn’t define me. I was not gay, I thought, because I could easily suppress whatever effeminate traits I had as a child. But, like all forms of bigotry, homophobia acts invisibly, causing us to judge ourselves the way we perceive others to be judging us. The books I read, the movies I watched, all told me my sexuality was sick, disgusting, diseased.

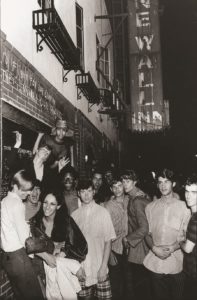

The difference that Stonewall made grew out of the refusal of the queens at the bar to accept — to internalize — the police harassment, brutality, and state-sponsored hate that was inflicted on them. It may not have been the first time that bar denizens fought back, but those four days of rioting in Manhattan in June 1969 made ripples that didn’t cease. The power unleashed in the rebellion was exemplary, and it was compounded by wide-ranging support in the queer community, which led to political action and organizing.

Like the slave rebellions in the antebellum South, and the Warsaw Ghetto uprising of Jews under Nazism, Stonewall countered the presumption that queers wouldn’t — and couldn’t — fight back. The difference between Stonewall and those prior eruptions was that it ended in triumph and the flowering of gay liberation. We had finally proved ourselves to be contenders.

I’m not saying that nonviolent dissent cannot wield the same power, but at that historical moment, the best way for the gays in Greenwich Village to demonstrate their lack of sheepishness was to refuse to be rounded up and arrested — to throw bricks and bottles, destroy property, burn police cars, and fight back wildly against the enforcers of injustice. The riots may have made it only to page 33 of the New York Times, but the way the world would regard queer people — and the way they regarded themselves — had shifted seismically.

Today, the crucible has expanded, and gender identity — as opposed to sexual orientation — is where the struggle has sharpened. #MeToo brought some justice to abusers and predators; Black Lives Matter has galvanized the nation. But, for me, in this month of Pride, I look back at the moment when the LGBTQ community unlocked its cage, and I recall the fictional suicide that filled me with terror. The lesson remains as true as it ever was: a simple act of exoneration — embracing your own identity — can save your life.