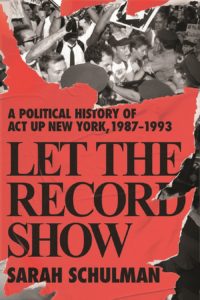

How do you tell the story of a movement without simply chronicling the lives of a few supposed leaders of that movement? Sarah Schulman tackles this question head-on in Let the Record Show: A Political History of ACT UP New York, 1987-1993. At stake, she explains, is the misbelief that “heroic individuals” bring about change in America. In reality, political change has always come from the strategic and zanily creative work of coalitions.

Schulman mines hundreds of interviews — many of which she recorded for the online ACT UP Oral History Project — to expand on this assertion in her mesmerizing, messy, multi-vocal celebration of groups working together and, at times, at cross purposes to address the desperate needs of people with AIDS (PWAs) in the harrowing first years of the epidemic. Schulman, a distinguished professor at the College of Staten Island, has published, among many works, four novels and five nonfiction books about AIDS, including Let the Record Show.

The 700-page book quickly dispatches activist and writer Larry Kramer, the supposed leader and hero of the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP) in New York in the late 1980s. Schulman writes that activists such as Kramer were all too willing to let reporters believe that AIDS was a gay male crisis. Kramer and other white, privileged gay men allowed reporters to credit them with progress to defeat HIV, obscuring the critically important work of so many others. Schulman writes that she publicly requested that Kramer ask reporters to interview people of color and women in ACT UP. “But Sarah,” Schulman recalls Kramer responding, “shouldn’t we use our best people?”

Exeunt: Larry Kramer. Enter: a motley crew of powerful, insightful characters, many of whose voices readers will experience as new and fascinating.

The activists Schulman finds most important belonged to an alphabet soup of affinity groups, committees, and coalitions working to promote gay liberation, feminism, and reproductive rights in New York in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Some arrived at ACT UP meetings out of a desire to find like-minded friends; others were drawn to cute guys in the organization; many came to meetings desperate to find treatments; and still others were outraged by national, state, and city government inaction. All were committed to making a difference. Training in the tactics of nonviolent resistance was a requirement, including lessons in how to orchestrate direct actions and participate in safe arrests after breaking the law. Schulman includes details about such training to instruct younger readers how to engage in social protests when so much work remains to be done.

Let the Record Show is at its magnificent best when Schulman uses selections from oral histories to summon the spirit of the most infamous of these direct actions. I defy readers to put down Schulman’s section on Stop the Church, for example, when activists interrupted Cardinal John O’Connor as he conducted Mass in 1989 at St. Patrick’s Cathedral. A moment of organized and impulsive intersectionality, the action brought together those advocating for condom distribution to promote safer sex and those advocating for reproductive rights within the Catholic Church. There was nothing “conciliatory, explanatory, or appeasing” about the action, Schulman writes. Instead, a variety of interests coalesced into “an unruly but impressive whole.”

Similarly, Schulman’s granular treatments of direct actions at Grand Central Station, the New York Stock Exchange, the Centers for Disease Control, the Food and Drug Administration, and the National Institutes of Health demonstrate ACT UP’s brilliant use of media and its iconoclastic organizing strategies.

Schulman explains throughout the book that ACT UP used so-called insiders and outsiders to exert pressure on tone-deaf figures, including Dr. Anthony Fauci, and profit-hungry corporations, such as Burroughs Wellcome. The insiders, often rich and white, sat in on meetings and convinced the powerful to explore new treatments and end adherence to supposedly blind clinical trials.

Schulman insists and demonstrates throughout that the outsiders — often low-income people of color and women — were equally important, participating in “zaps,” or quickly organized direct actions. They forced doctors, researchers, and government officials to recognize that, in women, HIV caused intractable vaginal yeast infections and pelvic inflammatory disease. As long as these symptoms weren’t recognized as criteria for a diagnosis of AIDS, women could not participate in government assistance programs, receive health insurance benefits, or access drug trials and therapies at a time when AIDS was a death sentence. Outsiders also got pharmaceutical companies and researchers to stop excluding “people of child-bearing potential” from clinical trials, a detail so outrageous that readers may find themselves flinching upon encountering it.

Tensions arose between insiders and outsiders, leading to a splinter in the group in 1992. Many attribute this split to an argument between two leaders, but Schulman sets the record straight again, bringing in a variety of perspectives to complicate dynamics.

Let the Record Show is simultaneously memoir and oral history, bringing to life the AIDS crisis in all of its horrifying, painful complexity. Schulman explains that she was “a rank-and-file member” of ACT UP between 1987 and 1992, leaving at the time of the insider-outsider split. At that point, with five other women, she co-founded the Lesbian Avengers, continuing her work fighting inequality in this country. Her commentaries enrich and enliven this documentary history of what another activist described as “the last of the great new social movements of the 20th century.”

On the Record

The event: Sarah Schulman talks about Let the Record Show

The time: Monday, June 14 at 6 p.m.

The place: Virtual and in-person at 389 Commercial St.; register at eastendbooksptown.com

The cost: $5 suggested donation