“I like a well-turned story,” says Patrick Radden Keefe. “I try to write stories that are engaging, the kinds of stories that you might not have an interest in at first — like the opioid crisis, or the Troubles in Northern Ireland. Hopefully, there’s an undertow that pulls you in, a strong narrative spine. If it feels like you’re reading a novel, then I’m doing it right.”

Keefe achieves this in Empire of Pain: The Secret History of the Sackler Dynasty. The book is about the Sacklers — the same family whose name bedecks the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Harvard University, and, until recently, the Louvre — and their role in the opioid epidemic. The Sacklers own Purdue Pharma, the maker of OxyContin. As reported in the Independent, this epidemic has struck with special vengeance on the Outer Cape.

Keefe is a staff writer at the New Yorker, which published “The Family That Built an Empire of Pain” in 2017, the article that formed the basis for this book. But he is also the creator of Wind of Change, a podcast about a song by the Scorpions possibly written by the CIA, and the author of Say Nothing: A True Story of Murder and Memory in Northern Ireland. On Wednesday, May 19 at 6 p.m., he will discuss Empire of Pain with host Karen Dukess as part of Castle Hill Author Talks.

Keefe humanizes and gets into the minds of the Sacklers. He treats them as more than “mustache-twirling villains,” aiming to understand “how can these people, over decades, make decisions that have disastrous consequences.” This is all the more impressive considering that no one from the Sackler family was willing to speak with Keefe — “In fact, they’ve been threatening to sue me the past couple of years,” he says. Even though the book reads like fiction, all of Keefe’s sources — interviews, court documents, emails, memos, confidential materials — are meticulously cited in the endnotes.

Empire of Pain details three generations of Sacklers; the book even has a handy family tree for reference. The first — brothers Arthur, Mortimer, and Raymond — purchased Purdue Frederick, which would later become Purdue Pharma. Arthur, the oldest, struck it rich marketing Valium. Later, Raymond’s son, Richard, marketed OxyContin using the same template — downplaying its addictiveness and aggressively promoting it to doctors. The youngest Sacklers remain ambivalent or in denial about the source of their wealth. The family still denies any responsibility for the hundreds of thousands of lives lost to the epidemic.

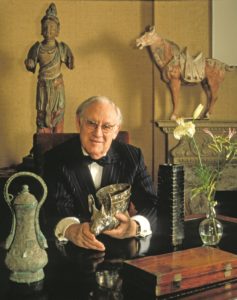

Considering that Arthur died years before OxyContin’s heyday, it is, perhaps, surprising that Keefe devotes about one-third of the book to him. Except that Arthur is a fascinating character. The son of Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe, he felt the pressure to be successful. He discovered that he had a knack for selling things — pharmaceuticals included. With his newfound wealth, he collected Asian art and donated to the arts and sciences. He even finagled his way into having a private office right in the middle of the Metropolitan Museum.

But Keefe argues that Arthur laid the corrupt groundwork for the subsequent two generations of Sacklers. He launched the Medical Tribune, a “newspaper” aimed at doctors, which advertised Arthur’s own products, and erased his name from the masthead. “Arthur Sackler basically believed there was no such thing as a conflict of interest,” says Keefe, who studied law before pursuing journalism. “There are things I wouldn’t do because I realize, as a journalist, I have a platform and responsibility, a transparency that I owe the reader.” Empire of Pain is all about power and its abuse.

“People marshal certain arguments, and then they gloss over certain facts,” says Keefe. “Arthur’s heirs suggest that he is pure as the driven snow, and as a result it is monstrous to suggest his name stands for anything other than that.”

From the perspective of the art world, the book raises questions. How do we reconcile the role that the Sacklers’ dirty money has played in art institutions? Does philanthropy always come from a place of guilt?

Historically — whether it’s the Medicis, Vanderbilts, or Carnegies — art has always been funded by the super-rich. And where there is money, there is corruption. As Keefe writes, activists like the photographer Nan Goldin have tried to get institutions to divest from the Sacklers. Keefe says one argument against that could be that “money is fungible,” or that “just because it’s tainted doesn’t mean you can’t, through a kind of transubstantiation, make it into a good thing.

“I don’t think these are easy issues,” continues Keefe. “Part of the reason that they are interesting is that they are hard. I’m conflicted about it all, to be honest with you.”

Keefe wrote the book while Covid dominated our lives. He says one result of the pandemic is that we have a greater awareness of pharmaceutical companies, and their names, because of the vaccines. Another relevant question is patent exclusivity: “After writing this book, it’s not surprising to me that the industry is pushing back.”

There’s an “awkwardness” in the timing, he says: “I say in the book that Pfizer bribed the head of antibiotics. I got my second Pfizer shot last week.” Despite having a healthy distrust in big pharma, “I’m totally dismayed,” he says, “by people who have the opportunity to get vaccinated and don’t get vaccinated.”

No Pain, No Gain

The event: Karen Dukess interviews Patrick Radden Keefe as part of Castle Hill Author Talks

The time: Wednesday, May 19, 6 p.m.

The place: Register for a Zoom link at castlehill.org

The cost: Free, donations appreciated