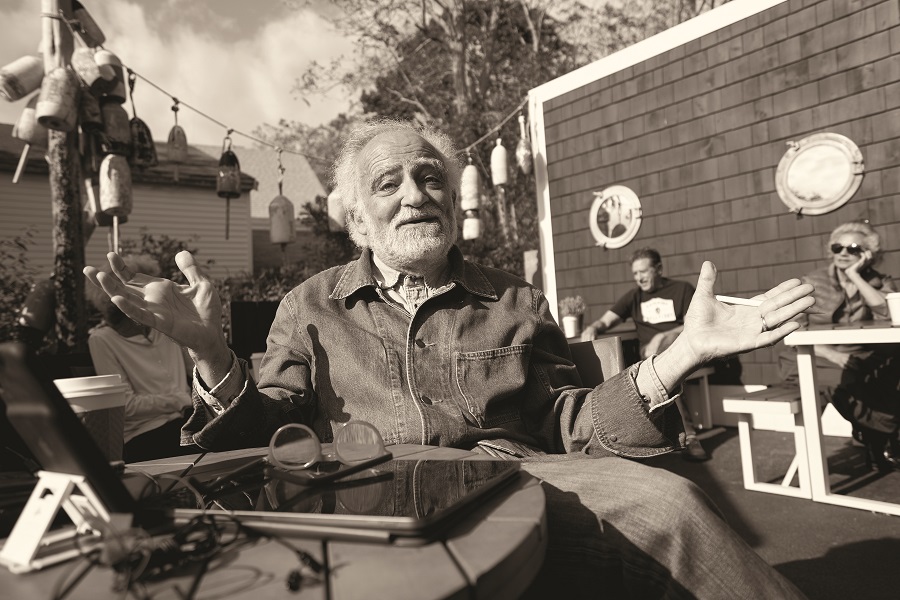

TONY KAHN / STORYTELLER / TRURO

Tony Kahn worked in public TV and radio for more than 40 years. He hosted a news program, pioneered podcasts, and told stories of ordinary people for NPR’s Morning Edition. And he wrote and produced Blacklisted, about his father, screenwriter Gordon Kahn. Tony and his wife have lived in Truro part-time for about 35 years. Here’s Tony in his words. To listen to Blacklisted, go to tonykahn.org/blacklisted.

As soon as I realized that my father was a writer, I wanted to be a writer. I was just wired to want to tell stories and to want to see words come together and turn into something that would take somebody else away. My father did not encourage me. I think it really frightened him to think that I might expose myself to the same ups and downs that he’d gone through as a writer. And that he was sort of trying to protect me and to protect himself from seeing himself repeated in me.

In my late 20s, I was luckily in Boston, which was the perfect place to be if you were interested in public broadcasting, either radio or television. Boston had the best public television station in the country. I got jobs writing for them. And, little by little, I realized that when somebody asked me, “What do you do?” I could say, “I’m a writer.” But I had to fight very hard against that sense that I wasn’t supposed to be doing this.

Blacklisted is the story of the 15 years that my father, mother, aunt Janet, brother Jim, and I went through as political exiles because of the Hollywood blacklist. From 1947 until my father’s death in 1962, we were on the run from the FBI, from neighbors who thought we were enemy agents, from anybody who was scared of being seen with us.

My father died when I was 17 years old. For me, writing Blacklisted was a way to update my understanding by hearing my father’s voice in his words and writing, and by hearing the voices of all the other people around us who were often so scared.

What I was aware of as a child was, no matter where I went, I was called a dirty name. In California, I was called a Communist by the neighbors. In Mexico, I was called “the gringo,” one of the people who had ruined Mexico. When we returned to the United States, I was called a wetback and a spic because I’d come from Mexico. The words might change, but the feeling always was: You don’t belong here. You’re not one of us.

My father was a screenwriter in Hollywood for 20 years. Then, he got into a lot of trouble with the movie industry because he was left wing. Anybody who had left-wing ideas at that point was suspected of being an enemy of the United States, a Communist. And the House Un-American Activities Committee was looking for Communists in hidden places.

So, my father was one of the very first screenwriters the committee called. You’re asked one thing. Are you a member of the Communist Party? Have you ever been? If you don’t tell us, and you don’t tell us the names of other Communists, we’re going to hold you in contempt, and that means you may go to prison.

So, for 15 years, my father couldn’t work under his own name and could barely work at all. He never gave in to the committee that was after him to betray his friends. And he never complained. I never got to talk to him about how hard things were. He never wanted to go there. And he died young, at age 60, of a heart attack. I think that has to be attributed in large measure to the bitterness that he had to swallow constantly.

It used to be said that radio makes the best pictures, ’cause they happen in your head. And what you need to make them happen are just the right inducements in the writing and in the sound effects and in the movement of those sound effects through the space that gets created when you listen.

Everything that happened in Blacklisted had to be something that somebody could visualize. It couldn’t be abstract, ever! It had to be here are these people, this is what they would say to each other, this is what happened to them, and then this happened, and then this happened.

If there were a rainstorm, it wasn’t a rainstorm from a sound effects album. It was the rainstorm that was happening, let’s say, during the rainy season in Mexico. And I would go down to Mexico, and I would record sheep and geese and ducks and pigs and the sounds of trucks, little things, a dog barking in the distance.

Blacklisted was maybe the most wonderful working experience of my life. At that point, there were enough advances in digital technology that you could, for about $10,000, pull together enough gear to record and edit and produce something that otherwise would have cost you, two or three years before, hundreds of thousands of dollars of studio time.

I had world-class actors who fell into my lap. I never recorded any of the actors together at the same time. So, I would record some in L.A., some in New York. But I would always play the person they were talking to in the drama. I would be working like a chef in my attic with all these elements, with my little equipment. I had miniaturized the world down to a place where I could just create.