In most biographies, the subject begins as a larger-than-life figure. Then, after we learn about imperfect relationships and personal quirks, he or she becomes more human.

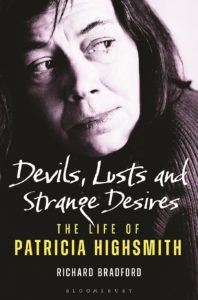

That’s not the case with Richard Bradford’s Devils, Lusts, and Strange Desires: The Life of Patricia Highsmith, published by Bloomsbury in January. As the book goes on, Highsmith becomes even more deplorable and less sympathetic. And, maybe, that’s just the way she’d want to be seen.

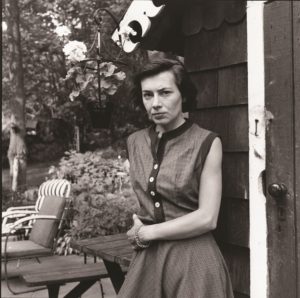

Highsmith would have been 100 years old this January had she not died in 1995. She was born in Fort Worth, Texas. Her parents, Jay Bernard Plangman and Mary Coates, divorced soon after her birth. She later learned that she had survived a botched abortion. Highsmith describes her relationship with her stepfather as almost incestuous.

Primarily a writer of psychological thrillers, Highsmith is best known for Strangers on a Train, adapted into an Alfred Hitchcock film; the five Tom Ripley novels (including The Talented Mr. Ripley and Ripley’s Game, each with more than one film adaptation); and the lesbian romance Carol, originally published as The Price of Salt under the pseudonym Claire Morgan, which was made into a film by Todd Haynes, starring Cate Blanchett and Rooney Mara. Bradford’s biography, however, does not presume an intimate familiarity with her work. It does a good job of summarizing, while leaving you wanting to read more.

Though Highsmith was openly lesbian long before Stonewall, her relationship to the LGBTQ community is fraught. No one is eager to claim her. She became more blatantly anti-Semitic over the course of her life. A self-described “Jew hater,” she believed that the Holocaust should be renamed “Holocaust Inc” or the “Semicaust.”

She was emotionally abusive, though never physically violent (despite fantasizing about it) to her partners. Turbulent relationships fueled her work — whenever she found herself in a happy one, she left. Highsmith was also a raging alcoholic, drinking gin, specifically, from morning to night.

She loved animals, perhaps because she believed them to be superior to human beings. She was so obsessed with snails that she kept a colony in her handbag. One time, at a dinner party, she let them loose, and watched with glee as they slithered over the table.

So, who is Richard Bradford? He is a British academic who specializes in literary biographies, having written ones on John Milton, Kingsley Amis, Martin Amis, Alan Sillitoe, and Philip Larkin (who used the pen name Brunette Coleman). Taking on the life of a problematic person such as Highsmith is no simple task, and Bradford is certainly well qualified to do it. But he doesn’t appear to have an LGBTQ bent, and this appears to be his first biography of a woman.

The book is quite dense. It’s challenging to remember all the names of Highsmith’s lovers: Madeleine, Rosalind, Kathleen, Kathryn, Ellen, Ann, Jeanne. And that’s only a fraction of the list. Their personalities bleed together, which is sort of apt. “Compared to Highsmith,” Bradford writes in his introduction, “the likes of Casanova, Errol Flynn and Lord Byron might be considered lethargic — even demure.”

Provincetown makes a brief appearance in book. Highsmith came to this “attractive coastal resort that had earned the reputation as a kind of Greenwich Village-on-Sea” with writer Marc Brandel, whom she met at Yaddo — one of the few men with whom she had a fling (though sex with him felt like “steel wool in the face”). While here, she had an affair with Ann Clark, a painter and ex-Vogue model.

Devils, Lusts, and Strange Desires follows on the heels of two other Highsmith biographies, by Andrew Wilson in 2003 and Joan Schenkar in 2009, both published by Bloomsbury. Wilson and Schenkar are so frequently cited by Bradford that they almost become characters in their own right.

Though Bradford’s biography is impressive, collating various sources — diary entries, interviews, books — into one very readable volume, it is unclear what, exactly, is new. There don’t appear to be any original interviews with ex-lovers — have they all since died? It seems unlikely, considering Highsmith’s penchant for younger women.

“In her early twenties, when fame was only a distant prospect,” writes Bradford, “Highsmith treated her diaries as works of fiction, often inventing people and events for which there is no empirical evidence. Later, when she became aware that her private documents would influence perceptions of her as an individual and writer after her death, she stopped making things up, factually at least, but she continued to enter observations and reflections by parts fantastical, unhinged and sometimes unpalatable.”

Considering how much Highsmith manipulated reality, how can we be sure that Bradford’s analysis is definitive? One can’t help but wonder if we are all pawns in Highsmith’s plan.

“It took a while for me to figure this out, but all those strange characters haunting other people, and thinking and writing about them — they were her. She was her writing,” says Madeleine, one of Highsmith’s ex-lovers, as quoted by Wilson.

This seems to be the conclusion that Bradford himself reaches: Highsmith’s life reflected her art — intriguing, caustic, amoral. And, in some ways, it did. She was a strange, maybe even disturbed, person. But the reader can’t help but feel as if there might be something deeper awaiting the next Highsmith biographer.