“Water touches us in so many ways,” says painter Marianne A. Kinzer. “It travels around the globe in the form of oceans, clouds, and rain. It moves through the stems of plants and trees, through birds, insects, and mammals. It permeates everything and shows the interconnectedness of all things. When studying water, you find yourself studying life.”

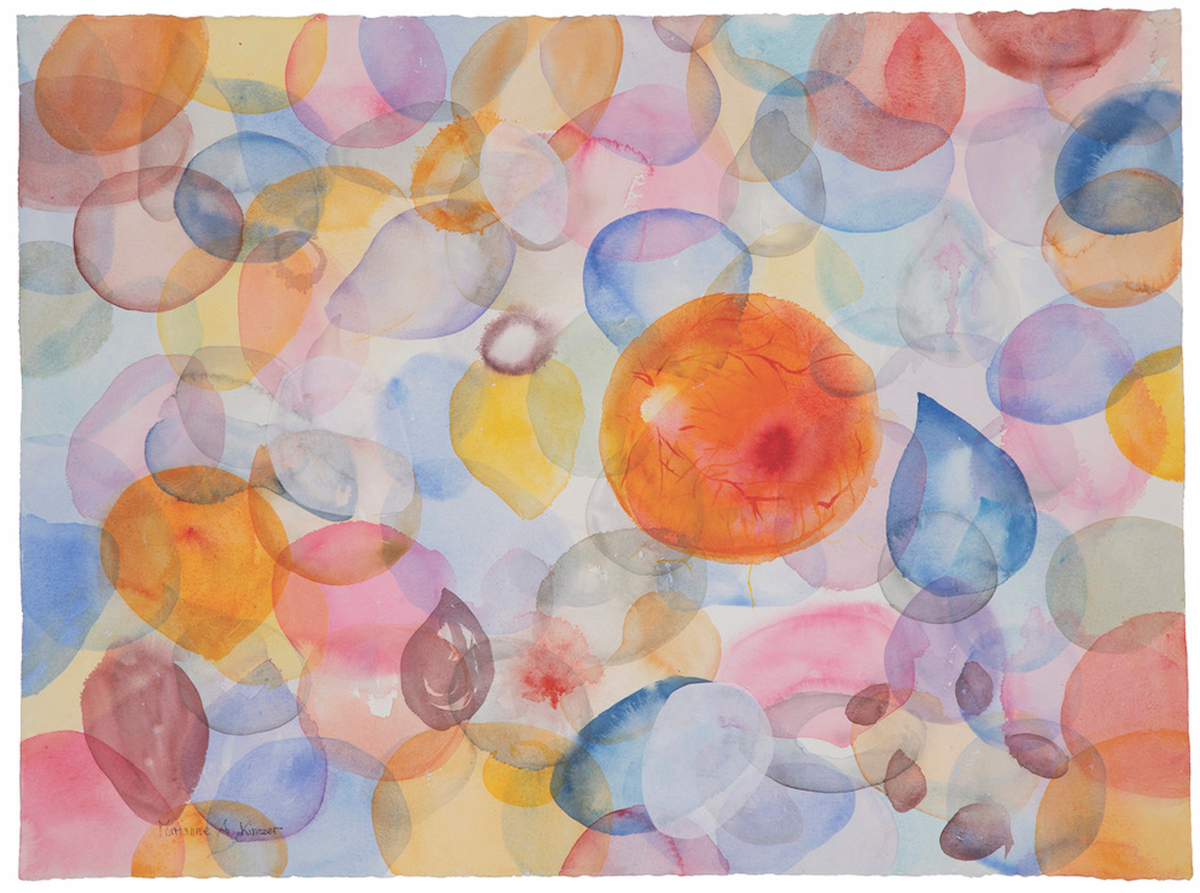

At the center of Kinzer’s artistic practice are abstract paintings that explore the presence and patterns of water in living organisms. She paints exclusively in watercolor — a medium that allows her to capture the ways in which water “spreads, bleeds, and flows.”

Kinzer begins each of her abstract pieces with a simple drop of water. “No drop is exactly like another,” she says. “I have learned to see variations of the drop shape in many natural forms, from seeds to fruits, cells to organs. The creative energy in a water drop seems almost limitless.”

In addition to her abstract paintings, Kinzer also does plein air landscapes of the Outer Cape. “When you look at landscapes, you look at water’s enormous impact on determining the character of a place,” she says. “Every place has its own water story.”

It was one specific “water story” that, early in Kinzer’s life, sparked her artistic mission. Born in a mountainous region near Frankfurt, in what was then West Germany, Kinzer moved to West Berlin, an oasis of freedom within Communist East Germany, to study painting at its University of the Arts.

“I lived in Berlin in the 1980s, when it was still a divided city, and I stayed there until the wall came down,” she says. “It was such a strange situation to live in a city surrounded by a wall.”

At the time, the Griebnitzsee, a lake within Berlin, was as divided as the city itself: partly in West Berlin, partly in the Communist East. “You could not swim out too far, because you could be arrested or even shot if you crossed to the other side,” Kinzer explains. “Swimming in that lake, I realized that water isn’t stoppable by a wall or a border. It moves constantly, connecting humans and countries.”

In Berlin, Kinzer met her husband, Stephen Kinzer, an American working as a New York Times foreign correspondent. The couple moved to Istanbul, Turkey, where they lived near the Bosporus, a channel of water between West and East — in this case, Europe and Asia. The Bosporus once again alerted Kinzer to the connecting nature of water.

In 2000, Kinzer and her husband crossed the Atlantic to settle in the U.S. They were first based in Chicago, where Kinzer continued her studies at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. There, in search of the city’s “water story,” Kinzer studied the Chicago River. Once a meandering watercourse that created pockets of wetlands “vital for the incubation of many creatures,” she says, the river had been redirected by engineers to carry polluted water from Chicago’s meat-processing industry away from Lake Michigan. “This human triumph over nature,” Kinzer says, “had devastating effects on a once species-rich environment.”

Kinzer joined a wetland restoration project. In one restored plot, she found a large white lotus blossom, and had an epiphany. Kinzer realized that the seed from which this flower had grown had been dormant for over 80 years and was brought to life by the presence of water. She began to search for a way of painting that reflected “the importance of water for life in general.”

The work of the German researcher Theodor Schwenk, who founded the Institute for Flow, opened her eyes “to the way water is inscribed in all living things,” Kinzer says. “I came to see that most of the shapes found in nature are informed by the flow of water, and I began to perceive flow patterns everywhere.”

Seeking a systematic way to visually compose these patterns, Kinzer turned to fractal geometry, which “describes natural phenomena much more closely than the better-known system of Euclidian geometry, based on idealized shapes.” Fractals, she found, exhibit the same kinds of repetitious yet imperfect patterns found over and over again in nature.

Kinzer divides her time between Boston and her second home beside the Pamet River in Truro. She paints abstract pieces in her studio in Boston’s South End and plein air landscapes on the Cape. She’s a board member at Truro Center for the Arts at Castle Hill, where she has taught watercolor painting since 2014 — and will lead a workshop there this June.

The “water story” of the Outer Cape, she says, is complex and ever-changing, defined by “the enormous and powerful ocean, and the tiny freshwater ponds.” One of her favorite spots to paint is on Bayberry Hill, which overlooks both. A tiny pond there, hiding behind the dunes, is the subject of many of Kinzer’s works.

There’s no better place to observe the impact of water on the environment than Ballston Beach and the Pamet River, where the landscape changes daily, she says. “It is simply mind-boggling.”