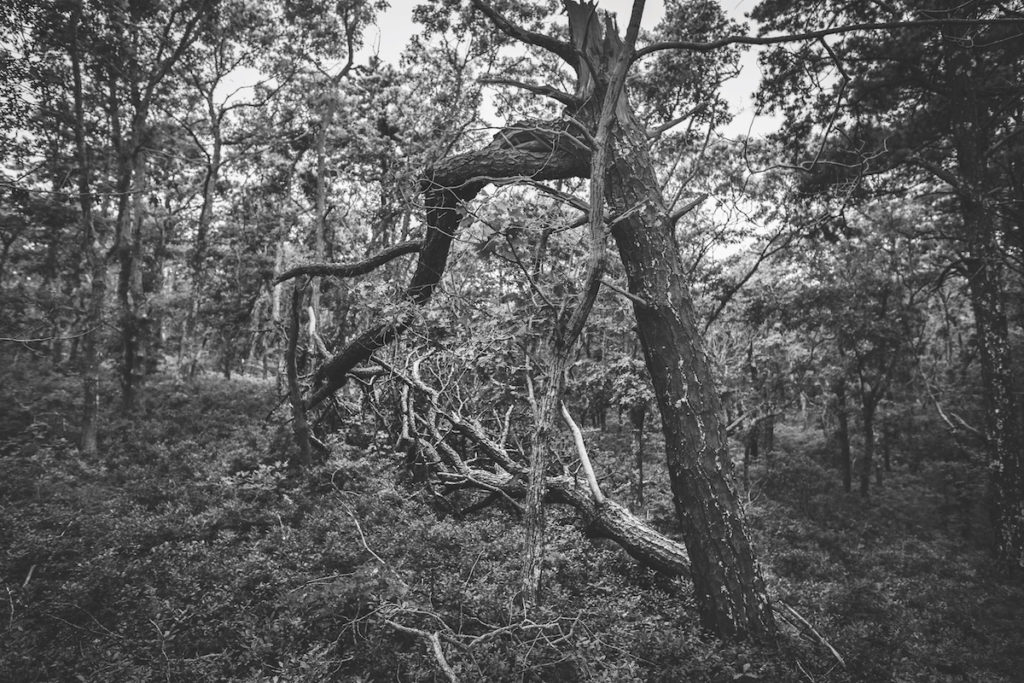

“Clear mind, tabula rasa, the four corners of the frame, calm breath,” photographer Lew Schwartz says as he prepares to shoot. “Someone on the street brushes away a mosquito, waves to a friend, or gives you the finger. People avoid collisions, come together, disappear. You can also see such gestures in the impossibly dense undergrowth of invasive brush or the way a pine tree grows toward the light for 20 to 30 years, then changes direction. They’re revealed by the lens and frozen in time by the shutter. It doesn’t matter whether it existed for one millionth of a second or a century.”

A philosopher in frames, Schwartz photographed the bustling streets of New York City for decades before retiring to Wellfleet with his wife, Chris, five years ago. Now, he focuses on the quiet disintegration of leaves and trees in the woods of the Outer Cape. He often posts work on Facebook, and a shot of his made it into the Members’ Juried Show at the Provincetown Art Association and Museum.

Born in Boston, Schwartz grew up on Long Island, N.Y. Fascinated by images at an early age, he became his family’s photographer when he was eight years old. His natural talent caught the eye of someone who worked at the hospital where his father was a radiologist. “That gentleman did all the publicity photos for the hospital,” Schwartz says. “He took me under his wing when I was about 10 and gave me a very thorough and unusually intense introduction to photography.”

In the 1960s, Schwartz went to N.Y.U. His student days introduced him, he says, to “an entire other world, accessible with the exact same equipment I was already using.” He was studying 14th-century English literature, yet he found himself spending most of his time in museums and photographing student protests on the streets.

“New York City in the ’60s was probably the most intellectually stimulating place you could be on the planet,” Schwartz says. “Those years had a permanent impact on the way I view life. I was volunteering at various photographic institutions in the city, such as the International Center of Photography. I knew Cornell Capa and his people, who founded the ‘concerned photographer movement.’ The emphasis was on socially relevant photography. At the same time, the Museum of Modern Art hosted the ‘New Documents’ exhibit, showing that documentary-style photography could be extremely expressive. The street work of the photographers in that show — Diane Arbus, Garry Winogrand, Lee Friedlander — was a total revelation.”

“New York City in the ’60s was probably the most intellectually stimulating place you could be on the planet,” Schwartz says. “Those years had a permanent impact on the way I view life. I was volunteering at various photographic institutions in the city, such as the International Center of Photography. I knew Cornell Capa and his people, who founded the ‘concerned photographer movement.’ The emphasis was on socially relevant photography. At the same time, the Museum of Modern Art hosted the ‘New Documents’ exhibit, showing that documentary-style photography could be extremely expressive. The street work of the photographers in that show — Diane Arbus, Garry Winogrand, Lee Friedlander — was a total revelation.”

Schwartz learned that even the most minor detail can contribute something to a photograph. “Arbus, Winogrand, and Friedlander compose images rather than photograph things. And their work is self-reflective. You come away knowing more about yourself than you do about the people in the photos.”

After graduating, Schwartz took a job teaching English in the New York public schools to avoid the Vietnam War draft, and moved to Brooklyn, where he married and raised a family. Though he worked in the schools until his retirement, Schwartz’s true passion remained photography. “I always got up very early so that I could have my afternoons available for photography,” Schwartz says. “I was on the streets at 2 p.m., literally every day, 365 days a year.”

Walking a city “dense with people,” Schwartz says, “you can’t have an agenda. You can’t look for good pictures. You respond to anything that grabs your eye, that strikes you as different: somebody carrying too many parcels or wearing too much makeup.”

Schwartz has learned to find ways of blending in so he can capture candid moments. “Once, during the annual Mermaid Parade on Coney Island, I joined a group of stripteasers,” he says with a chuckle. “I didn’t strip myself, but I was able to march with them and take photographs of the crowd.” Likewise, his strategy during parades in Provincetown is to “hop onto a vehicle and photograph people from there. In New York, I’d be arrested!”

During a recent Carnival parade, Schwartz snapped a picture of a young woman in a golden top à la Madonna. “She was so self-absorbed, sitting next to this old guy with a camera, that she wasn’t even aware that I was there,” he says.

Schwartz uses a 35-mm camera and leaves the film in the freezer for some time before developing it. “If you look at your images right away, you tend to answer the question: did I get what I wanted? And that’s really no good,” he says. He’s always “unpeeling the depth of a single image.” Recently, he’s been following the decay of hosta leaves and the shifting forms of falling pines, going back to the same leaf or branch for weeks.

“Early on, it became apparent to me that the fall of a large tree didn’t signal its death, but rather the beginning of a new phase,” Schwartz says. “This pivotal time between seasonal growth is really just part of a process. As leaves decay, they become the residence of many tiny insects, fungi, and bacteria. Similarly, a fallen tree is teeming with life. Its significance comes from being part of a much larger narrative.”