There’s an obsessiveness to the art of Siân Robertson — multiple objects are organized, following rules and patterns. But an opposite impulse is also manifest — a relentless creativity.

It’s kind of a paradox, a dialectic: Robertson says her organizing principles are “freeing,” and she sets them up whenever she feels blocked. “You have to have a structure,” she says. “There needs to be some boundaries. That frees you to be creative within the boundaries.”

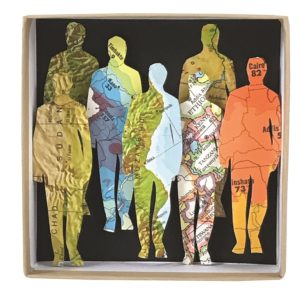

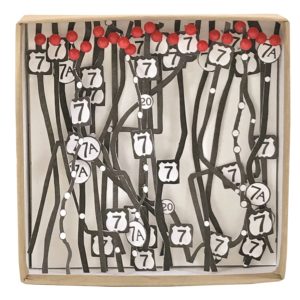

Robertson’s preferred medium is used maps — they must be used because it gives them individuality, a story. She also likes stamps (used stamps), vintage photographs, pushpins (the kind used with maps), and other printed material, such as color charts, figurative images, pop designs. She likes to take the work into the third dimension, giving it depth — in books, boxes, or blocks of acrylic.

“I’m drawn by the colors and shapes and lines,” Robertson says. “That’s what attracts me to maps. They might be of Provincetown or Wales” — Robertson was born in Wales and raised in a small village there; she came to the U.S. at the age of 29 — “or of somewhere I had a vacation I enjoyed. But I never choose them because of the geography.”

For Robertson’s current project, “Around the World in 366 Boxes,” she created a new, 3.5-inch-square box, one inch deep, for every single day of the year 2020. “It had to start on January 1st,” she says, obsessive as always. And there are three rules: “They have to be three-dimensional; everything has to fit in the box; and there has to be some sort of cartographic element.”

The entire year of boxes will be on view (and for sale) at Adam Peck Gallery in Provincetown, starting on Tuesday, Dec. 22. Actually, the entire year won’t be seen until Jan. 1, when those last days in December are done. Then the show closes on Jan. 3.

“For me, seeing them all laid out is the most important thing,” Robertson says. “They’re laid out exactly like a calendar — an American calendar, Sunday to Saturday. British calendars start on a Monday.”

She’s coming off a residency at the Higgins Art Gallery at Cape Cod Community College, where she created a giant wall collage of map routes, cut out and reconnected like a maze. Such projects are challenging and exciting to Robertson, who only recently has come to define herself as an artist.

“I was always a very crafty kid,” she says. “I used to make these collages and decorate my bedroom. I would knit and do embroidery. It never felt like art.”

When the local school system sent students on a career path, “I couldn’t draw, so I didn’t take art,” she says. “When I went to college, I trained to be a teacher for young kids, five to nine. But I never actually went into it. I had a few different jobs, mostly in nonprofits and the trade union sector. I was always interested in art. I just never saw myself as someone who created it.”

When Robertson came to America, it was supposed to be for a few months. She toured the country by rail. Then, in San Francisco, she met her husband, Nick.

“We came to Provincetown as part of our honeymoon,” she says. “ ‘This place is fantastic,’ I said. ‘We’ve got to move here.’ We did, about five years later.”

They had a gift store, Traders Village, at 220 Commercial St. (later home to Wa and Map), which they eventually sold and got jobs — Nick at town hall, Siân at Kobalt Gallery.

“All this time, I’m doing my little collages on the kitchen table,” Robertson says. She credits Provincetown with her transformation from crafter to artist: “There was a very accessible artist community here, a community that’s very encouraging, if you have any artistic inclination.” She became part of the conversation, joining the Provincetown Art Association and Museum, finding mentors, submitting pieces to members’ shows. When she and Nick built a home for themselves in Truro, she got her own studio.

Robertson says she used to make collages by altering other artists’ work: she was inspired by the series of paintings Picasso made that were based on Velázquez’s Las Meninas. But she slowly gained the confidence to follow her own aesthetic impulses. She loved and collected maps, so she turned her trusty X-Acto knife on them, isolating the details that attracted her.

She started showing in galleries here in 2015. “My first show, at A Gallery, nearly sold out on opening night,” she says. “I was a changed person after that.” She did her first year-long, every-day-a-new-piece project soon after. Her “excavated” maps got deeper — layered page by page in a book, in between sheets of clear acrylic, rolled up into balls.

Robertson says she’s comfortable with abstraction and no longer feels the need to tell stories in her work. She appreciates the metaphorical aspects of maps — the connectivity, the symbols standing in for the real world. But the heart of her work is the sensuousness of her constructions. She speaks rapturously of the “sound” an X-Acto knife makes while cutting paper, even though she always works with the radio on and “hears” through her fingers.

“I make stuff because I can’t not make it,” Robertson says. “I don’t have any other purpose.”

All in a Day’s Work

The event: “Around the World in 366 Boxes: A Daily Art Project for 2020,” an exhibit of artwork by Siân Robertson

The time: Tuesday, Dec. 22 through Jan. 3; call gallery for hours, 508-237-1840

The place: Adam Peck Gallery, 142 Commercial St., or sianrobertsonart.com/around-the-world-in-366-boxes

The cost: The exhibit is free; the boxes, $250 each